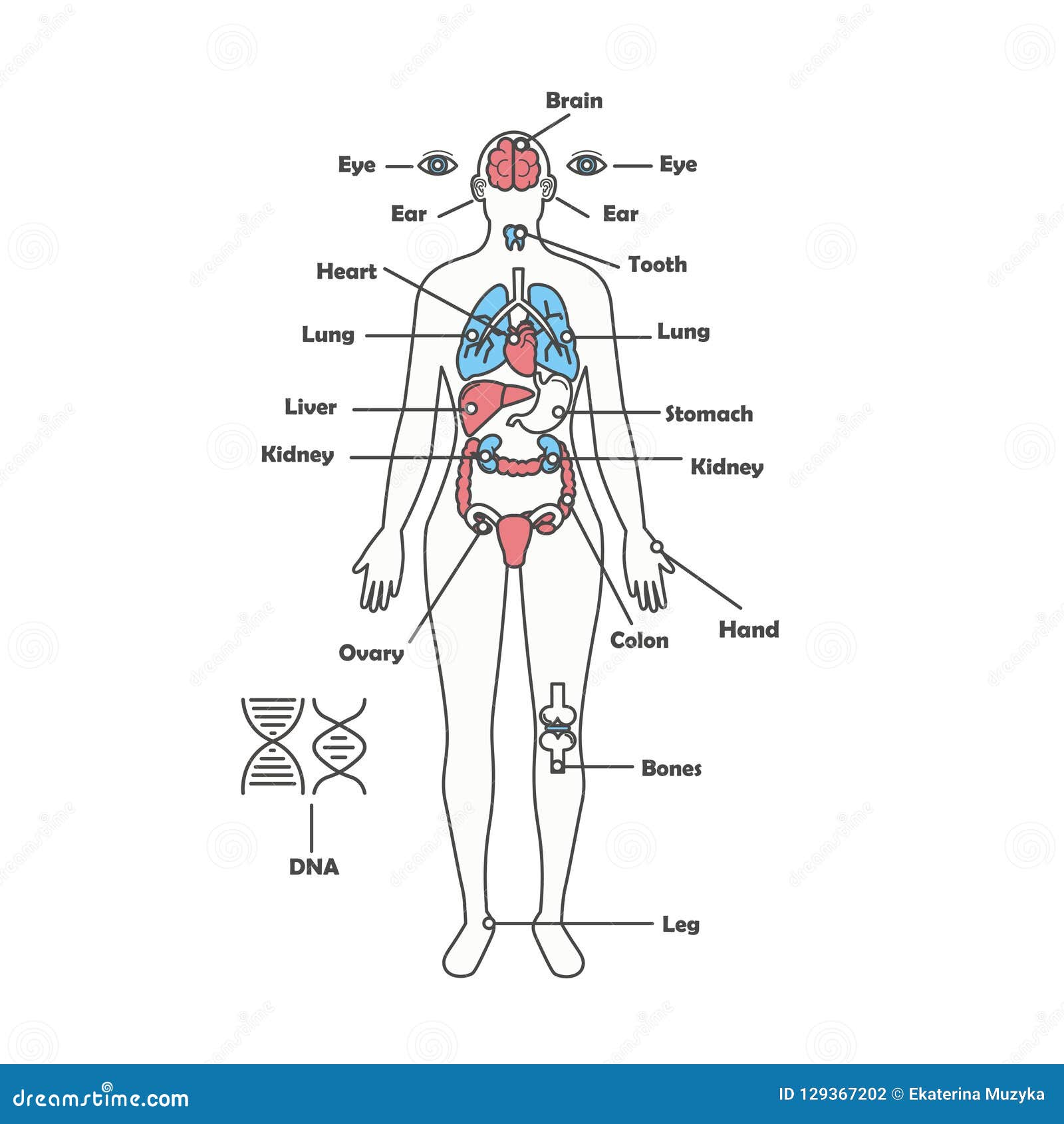

You’ve probably seen them a thousand times in biology textbooks. Those rigid, translucent plastic-looking torsos that make everything look perfectly spaced out, like a well-organized suitcase. But honestly? If you actually looked at an internal organs diagram female and compared it to a real human body during surgery or an MRI, you’d realize those diagrams are basically the "Instagram filter" version of anatomy.

Everything is crowded. It's squished.

✨ Don't miss: The Birth of the Clinic: Why Foucault Still Matters for Modern Medicine

In a real female body, the layout isn't just a static map; it’s a shifting, living puzzle where the "pieces" are constantly pushing against each other. Especially when you factor in things like the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or even just having a full bladder. Most people think the liver is "here" and the stomach is "there," but the reality is much more fluid and, frankly, a bit messy.

Why your internal organs diagram female looks the way it does

Standard anatomical models usually default to a "neutral" position. They show the heart nestled between the lungs, the liver tucked under the right ribs, and the reproductive system sitting low in the pelvis. It looks clean.

But it’s a lie. Well, a white lie.

In 2023, researchers at North Carolina State University and other institutions started highlighting how much "anatomical variation" actually matters. Some people have larger livers; some have colons that take a much more scenic route through the abdomen than the diagrams suggest. When we look at a female-specific diagram, the biggest differentiator is the pelvic cavity. While the male anatomy has a relatively straightforward "exit" for the urinary and digestive systems, the female anatomy has to accommodate the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries right in the middle of everything.

The Great Space Squeeze

Take the bladder. On a paper diagram, it looks like a tidy little balloon sitting in front of the uterus. In real life? When that bladder fills up, it shoves the uterus backward. When a person is pregnant, the uterus expands from the size of a small pear to the size of a watermelon, literally forcing the intestines upward toward the diaphragm and squishing the stomach. This is why heartburn is so common in late pregnancy—your stomach is being physically pancaked against your ribs.

Most diagrams don't show that movement. They show a snapshot.

The Pelvic Floor: The most underrated part of the map

If you look at the bottom of a high-quality internal organs diagram female, you'll see a bowl-shaped group of muscles. This is the pelvic floor. Think of it as a hammock. It’s not an "organ" in the traditional sense, but without it, your organs would literally fall out.

It supports the:

- Bladder

- Uterus

- Rectum

Dr. Arnold Kegel made these muscles famous back in the 1940s, but we’re still arguably bad at teaching people where they actually sit. In many 2D diagrams, the pelvic floor is barely a line. In reality, it’s a complex, multi-layered mesh that has to be both incredibly strong and incredibly flexible. When it weakens—which can happen due to age, childbirth, or even chronic coughing—you get "prolapse." This is where the organs actually start to shift downward. A diagram shows them in their "correct" place, but for millions of women, the map has shifted.

The Liver and the Right Side Bias

The liver is a beast. It’s the largest internal organ, and it dominates the upper right quadrant of the female torso. If you’re looking at a diagram, the liver is that big, dark red wedge. It’s responsible for over 500 functions, from detoxifying blood to producing bile.

Interestingly, women’s livers are often slightly smaller than men’s in absolute terms, but they frequently work "harder" relative to body size when processing certain medications or alcohol. This is a nuance you won't find on a basic 2D chart. Below the liver sits the gallbladder. It’s a tiny, pear-shaped sac that stores bile. If you’ve ever had a "gallbladder attack," you know exactly where it is: a sharp, stabbing pain right under the right rib cage that can radiate to your shoulder blade.

The Digestive Transit

Behind and below the liver, the stomach leads into the small intestine, which then connects to the large intestine (the colon).

The colon in a female body is particularly interesting. Studies, including those published in journals like Gastroenterology, have noted that the female colon is often longer than the male colon, particularly the "redundant" or "tortuous" colon. Because the female pelvis is wider to allow for childbirth, the colon has more room to "sink" down into the pelvic area. This extra length and the way it twists around the reproductive organs is one reason why women statistically report higher rates of bloating and IBS than men.

The diagram shows a nice, neat "U" shape for the large intestine. The reality for many is more like a tangled garden hose.

The Kidney and Adrenal Connection

Tucked way in the back—closer to your spine than your belly button—are the kidneys. People often point to their lower back when they talk about kidney pain, but they’re actually higher up, partially protected by the lower ribs. On top of each kidney sits a tiny, hat-like structure called the adrenal gland.

These are the "stress" centers. They pump out cortisol and adrenaline. In the context of female anatomy, these glands are part of a delicate feedback loop with the ovaries. They aren't just "isolated" filters; they are part of a massive chemical communication network.

The Reproductive Hub: Ovaries and Uterus

This is usually the focal point of an internal organs diagram female.

The uterus is a muscular marvel. It sits right behind the bladder and in front of the rectum. Flanking it are the fallopian tubes, which reach out like arms toward the ovaries. But here’s the kicker: the fallopian tubes aren't actually "glued" to the ovaries. There’s a tiny gap. When an egg is released, the "fimbriae" (finger-like projections at the end of the tubes) have to actively sweep the egg inside.

It’s a bit like trying to catch a baseball with a loose glove.

The ovaries themselves are about the size of an almond. They don't stay in one perfect spot, either. Depending on your age and whether you've been pregnant, they can shift around quite a bit in the pelvic cavity.

Thoracic Organs: Heart and Lungs

Moving up past the diaphragm—the thin sheet of muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen—we find the "engine room."

✨ Don't miss: Newborn Only Sleeps When Held: Why This Happens and How to Actually Get Some Rest

The heart sits slightly to the left of center. The lungs surround it. A common misconception is that the lungs are just empty balloons. In a detailed diagram, you’d see the "bronchial tree," a fractal-like network of tubes getting smaller and smaller until they reach the alveoli.

One thing people often miss: the right lung has three lobes, but the left lung only has two. Why? To make room for the heart. The body is all about compromise.

Misconceptions that lead to bad self-diagnosis

We often use diagrams to figure out why we hurt. "I have a pain right here, so it must be my appendix."

The appendix is usually in the lower right abdomen. But "referred pain" is a real thing. Sometimes a problem with the gallbladder feels like it’s in the shoulder. Sometimes a problem with the ovaries feels like lower back pain.

Also, "Situs Inversus" is a real (though rare) condition where all your organs are mirrored. Your heart is on the right, your liver is on the left. If you had that and looked at a standard diagram, you’d be very confused.

How to use this information practically

Visualizing your anatomy isn't just for medical students. It helps you advocate for yourself at the doctor’s office.

If you’re looking at an internal organs diagram female because you’re experiencing discomfort, don't just look at the organ. Look at what’s around it. Are you bloated? That’s your intestines putting pressure on your bladder. Is your period coming? That’s your uterus contracting and potentially irritating the nearby bowels (yes, "period poops" are a direct result of organ proximity and hormones).

📖 Related: How Much Do Kids Braces Cost: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Steps for Better Organ Health

- Learn your "normal" baseline. Feel your abdomen when you're healthy. Know where your rib cage ends and where things feel soft versus firm.

- Hydrate for the "Filter Organs." Your kidneys and liver are your primary detox centers. They don't need "cleanses" or "juices"; they need water to flush waste effectively.

- Move to massage your organs. Gentle movement, like yoga or walking, physically moves your intestines, helping with digestion and preventing the "stagnation" that leads to bloating.

- Watch your posture. Slouching literally compresses your internal organs. If you sit hunched over a laptop, you’re squishing your lungs and stomach, which can lead to shallower breathing and slower digestion.

- Get specific with doctors. Instead of saying "my stomach hurts," use your knowledge of the diagram. Is it "upper right under the ribs" (Liver/Gallbladder)? Or "low and central" (Bladder/Uterus)?

The human body isn't a static map. It’s a 3D, moving, breathing ecosystem. When you look at a diagram, remember that it's just a starting point. Your own "map" is unique, and it changes every single day.

If you really want to understand your internal layout, the next step is to pay attention to how your body reacts to different triggers—food, stress, and your cycle. That’s the "live" version of the diagram that actually matters for your health.

Expert Insight: Most anatomical models in history were based on the male "standard," with female organs simply swapped in. Modern medicine is finally catching up to the fact that the spatial relationships in the female torso are distinct and require their own specific study, especially regarding how the immune system and the lymphatic system interact with the reproductive organs. When looking at a diagram, always ensure it is a high-fidelity modern version that accounts for the pelvic floor and connective tissues like the mesentery, which we now classify as a full organ in its own right.

Immediate Next Steps:

- Check your posture right now. Lift your ribcage away from your hips to give your digestive organs space.

- Track "referred pain" locations if you have recurring discomfort to see if they correlate with organ clusters.

- Use a high-quality 3D anatomy app to see how organs layer over one another rather than just seeing them as side-by-side icons.