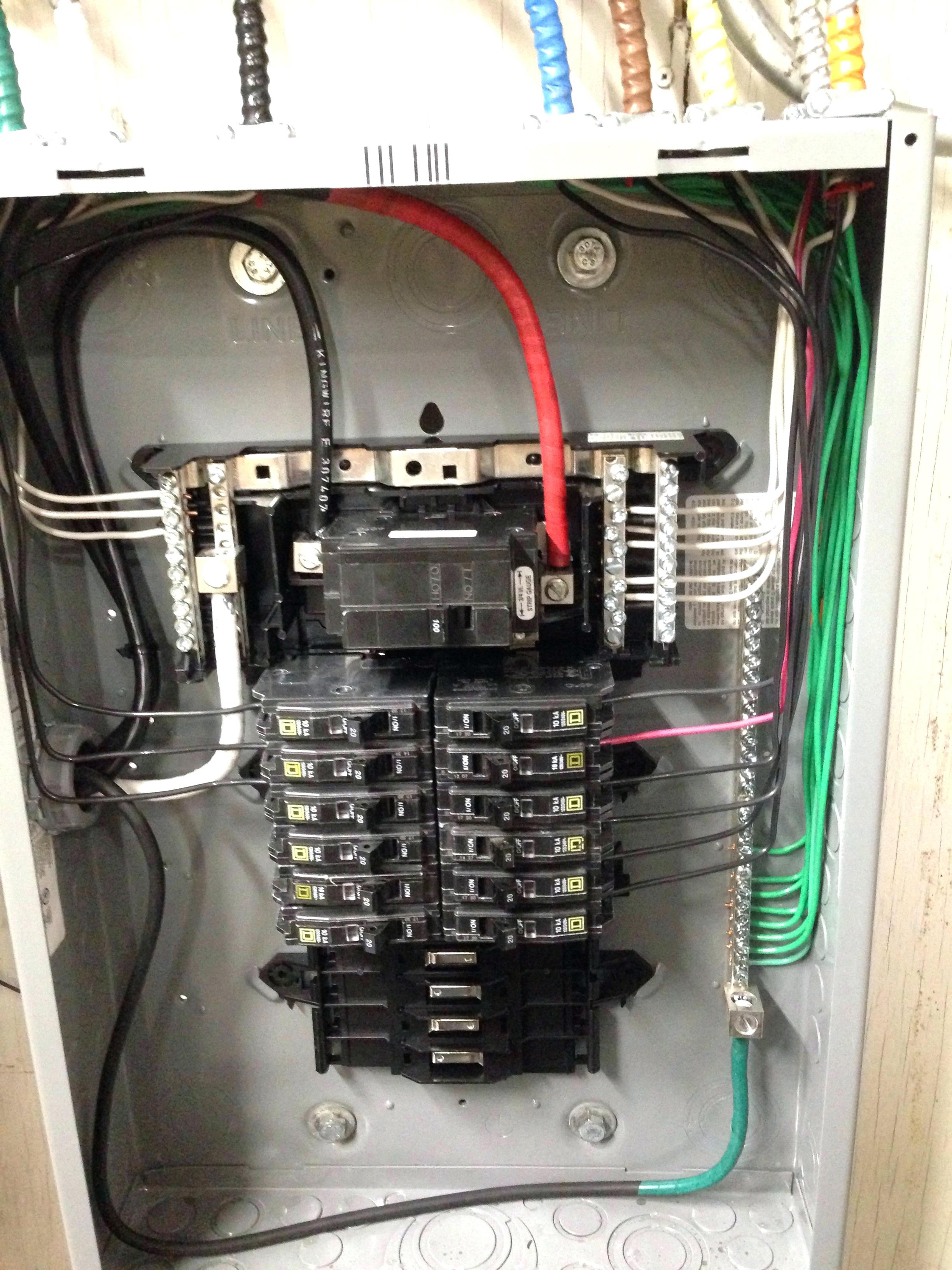

You're staring at your main electrical breaker box and it’s a mess. Every slot is filled. There’s a tangled web of Romex, and you’re pretty sure if you try to squeeze in one more dedicated circuit for that EV charger or the new workshop tools, something is going to go pop. This is usually the moment people start Googling a 100 amp sub panel. It sounds like the perfect "bucket" to hold all your extra electrical needs, but honestly, most DIYers—and even some junior apprentices—trip over the math before they even buy the wire.

It’s not just a smaller box. It’s a strategic extension of your home’s nervous system.

If you think a 100 amp sub panel magically adds 100 amps of power to your house, I have some bad news. It doesn't. Your house is limited by the main service entrance—usually 200 amps in modern homes or 100 amps in older ones. Adding a sub panel is more about organization and proximity than it is about creating "new" electricity out of thin air. You're basically taking a slice of your existing power pie and moving it to a different room.

Why the 100 Amp Size is the "Goldilocks" Choice

Why 100 amps? Why not 30 or 60?

Most people go for the 100 amp sub panel because it offers the most versatility for future-proofing. If you’re finishing a basement, you might only need 30 amps today for some LED lights and a TV. But five years from now? You might want a sauna. Or a kitchenette with a microwave and a hot plate. A 60-amp feed might handle it, but the price difference in the physical panel box between a 60 and a 100 is often less than twenty bucks.

The real cost isn't the box. It’s the copper.

The National Electrical Code (NEC) is pretty strict here. For a 100-amp load, you’re usually looking at #4 copper wire or #2 aluminum for the feeders. If you’re running that wire 50 feet across a finished ceiling, you’re going to feel that price tag in your wallet. Aluminum is significantly cheaper and perfectly safe for feeder lines—provided you use the right lugs and anti-oxidant paste—but some old-school guys will fight you on that until they're blue in the face.

The Four-Wire Rule: Where Most People Fail Inspection

Here is the big one. If you take away only one thing from this, let it be the "four-wire" requirement.

In your main service panel, your neutral wires (the white ones) and your ground wires (the bare or green ones) all hang out on the same metal bar. They’re bonded. But the second you move to a 100 amp sub panel, that rule changes completely. You must keep them separated.

- Two "hot" legs (usually black and red).

- One neutral wire (white).

- One equipment grounding conductor (green or bare).

If you bond the neutral and ground in a sub panel, you’re creating a parallel path for the return current. That’s a fancy way of saying your metal panel box could become "hot" under the right (or wrong) conditions. It’s a massive safety hazard and the quickest way to fail an inspection. You have to remove the "bonding screw" or "bonding strap" that comes pre-installed in almost every panel you buy at Home Depot or Lowe's.

Calculating the Load Without Blowing a Fuse

You can't just keep adding stuff.

Before you mount that 100 amp sub panel, you need to do a load calculation. It’s a bit of a headache. You have to look at the "nameplate" ratings of your heavy hitters: the HVAC, the water heater, the range, and that power-hungry dryer. If your main service is only 100 amps and you try to pull 80 amps through a sub panel while the AC is kicking on, you’re going to trip the main breaker.

Then you’re sitting in the dark.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Mol Wt of KOH: Why This Number Changes Everything in Your Lab

Think about the "diversity of load." You aren't running the vacuum, the toaster, the space heater, and the table saw all at the exact same millisecond. Or at least, you shouldn't be. Professional electricians use NEC Article 220 to figure out the "calculated load" versus the "connected load."

I’ve seen guys put a 100 amp sub panel in a detached garage and try to run it off a 30-amp breaker in the main house because they didn't want to dig a deeper trench for the heavier wire. It works for a lightbulb. It doesn't work when you turn on the air compressor.

Distance and the "Voltage Drop" Nightmare

Electricity is a bit like water in a hose. The longer the hose, the less pressure you have at the end.

If your 100 amp sub panel is going into a shed 150 feet away from the house, you can’t just use the standard wire size. You have to "upsize" to account for voltage drop. If the voltage drops too low, your motors (like in a fridge or a saw) will run hot and eventually burn out. It’s expensive and annoying.

For long runs, you might end up using 1/0 or even 2/0 aluminum just to get a clean 100 amps out to a detached building. And don't forget the trench. If you’re burying direct-burial cable (UF-B), it usually needs to be 24 inches deep. If you’re using PVC conduit, you can often get away with 18 inches. Check your local codes because some jurisdictions are way more "intense" about this than others.

Ground Rods for Detached Buildings

This is a nuance that catches people off guard. If your 100 amp sub panel is in the same building as the main panel, you just run your four wires and you’re done.

But if it’s in a separate building? You need a local grounding system.

Usually, that means pounding two 8-foot copper-clad steel rods into the earth, spaced at least 6 feet apart. These rods connect to the ground bar in your sub panel. This doesn't replace the ground wire coming from the house; it supplements it. It's there to handle things like lightning strikes or high-voltage surges.

It's a lot of physical labor. Pounding a ground rod into rocky soil is a workout you didn't ask for.

Choosing the Right Brand

Honestly, stay consistent. If your main house uses Square D QO breakers, it’s a lot easier if your sub panel uses them too. Why? Because then you only need to keep one type of spare breaker in your junk drawer.

- Square D QO: The industry "premium" standard. They have a little red flag that shows when they’re tripped.

- Leviton: The new kids on the block with the white, sleek-looking panels. They are very easy to wire because the breakers plug in without being wired directly.

- Eaton/Cutler-Hammer: Solid, reliable, and found in about half the houses in America.

- GE: Generally the budget option, but they work fine.

Just make sure the "AIC rating" (Ampere Interrupting Capacity) matches what’s required by your local utility. Usually 10k or 22k.

Common Misconceptions About Sub Panels

One thing I hear all the time: "I need a 100 amp sub panel so I can have more power."

Again, no. You are just redistributing.

Another one: "I can just 'double-tap' the main lugs to feed the sub panel."

Absolutely not. You must feed the sub panel from a dedicated breaker in the main panel. That breaker protects the wire (the feeders) going to the sub panel. If that wire shorts out and there's no breaker at the start of it, you have a 200-amp fireball waiting to happen.

🔗 Read more: The Sign for Less Than or Equal To: How to Find It, Type It, and Use It Like a Pro

Actionable Steps for Success

If you're ready to pull the trigger on this project, don't just wing it.

First, perform a residential load calculation. There are plenty of online calculators based on NEC 220.30 that will tell you if your main service can even handle an additional high-load area. If you're already at 90% capacity, adding a workshop is going to require a service upgrade from the utility company first.

Second, map your route. Measure the actual path the wire will take—up walls, through joists, around corners. Add 10% for "waste" because there is nothing worse than being 2 feet short on a $400 roll of wire.

Third, buy a "Main Lug" panel, not a "Main Breaker" panel, unless you want a local disconnect. In a detached building, you actually need a main breaker in the sub panel to act as a shut-off switch. In the same building, it’s optional.

Finally, get a permit. Seriously. If your house burns down—even if it has nothing to do with your wiring—and the insurance adjuster sees an unpermitted 100 amp sub panel, they have a massive loophole to deny your claim. It’s not worth the risk.

Check your wire terminations after a month of use. Thermal expansion and contraction can loosen those big feeder lugs. Give them a quick turn (with the power off!) to ensure they’re still torqued to the manufacturer’s specs. Loose wires create heat, and heat creates fires. Stay safe, keep your neutrals and grounds separate, and enjoy the luxury of not having to run to the garage every time the hair dryer and the microwave are on at the same time.