Most people imagine a glowing green ooze or a ticking time bomb when they think about the space inside the nuclear reactor. It’s the Hollywood effect. In reality, if you were standing right there next to the core—provided you weren't being cooked by gamma radiation—it would be strangely quiet. Maybe a low hum. A lot of stainless steel.

It's basically just a very fancy way to boil water.

That sounds reductive, but honestly, that’s the heart of it. We’ve mastered the art of splitting the atom just so we can spin a turbine. But the physics happening in that pressurized silence is anything but simple. It’s a violent, subatomic mosh pit governed by the laws of probability and heat transfer.

The Blue Glow is Real (But It's Not What You Think)

If you look into a pool-type research reactor while it’s running, you see it. Cherenkov radiation. It’s this haunting, ghostly blue light that seems to hum with energy.

It isn't magic. It happens because particles—specifically electrons—are traveling through the water faster than the speed of light in that medium. Nothing beats the speed of light in a vacuum, sure. But in water? Light slows down to about 75% of its usual speed. The particles coming off the fuel rods don't care about that speed limit. They blast through, creating a "photonic shockwave" that we see as blue light. It’s the optical version of a sonic boom.

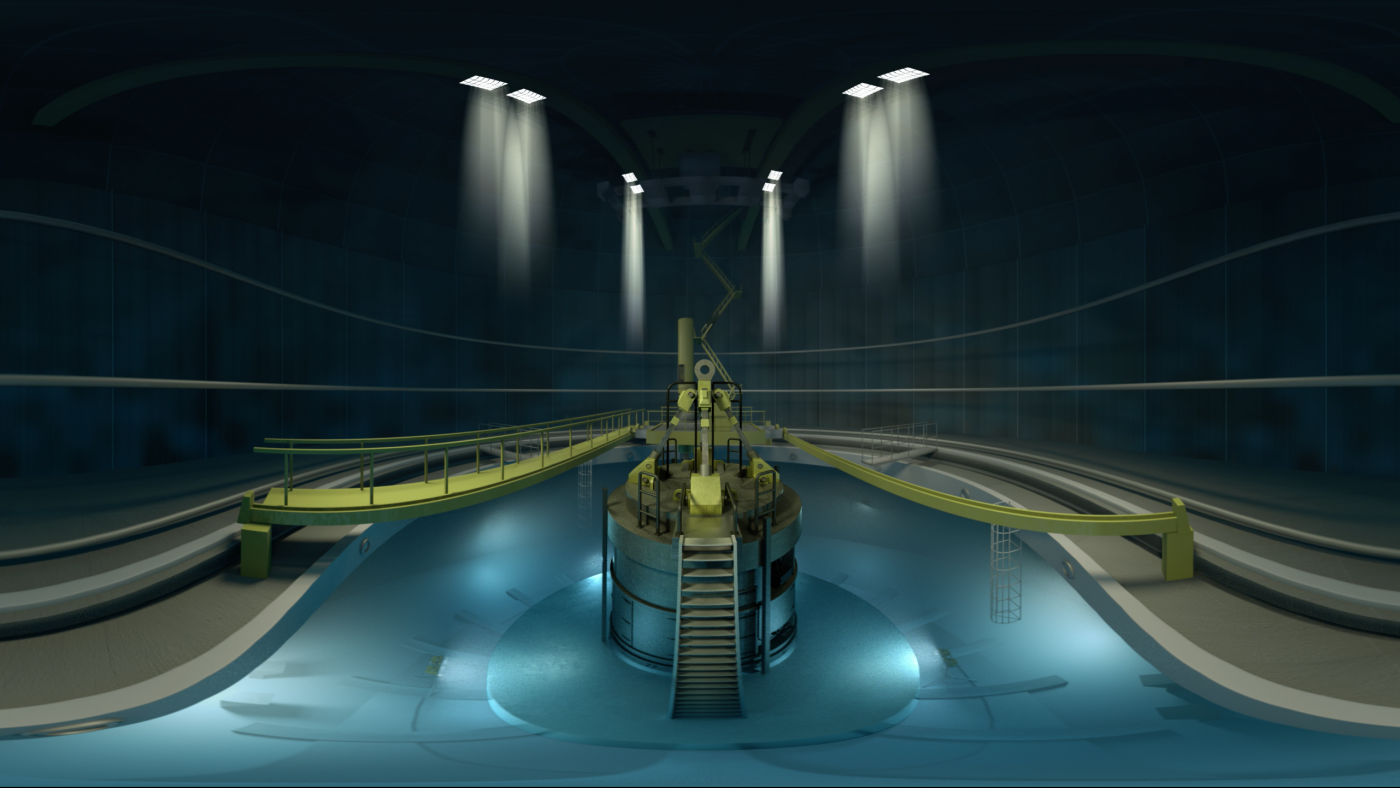

Inside a commercial power reactor, like a Westinghouse Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR), you wouldn't actually see this because the whole thing is encased in a massive steel pressure vessel. The walls are often eight to ten inches thick. It has to be. You’re dealing with pressures around 2,250 pounds per square inch (psi). If that vessel let go, it wouldn't just be a leak; it would be a catastrophic flash-steam explosion.

👉 See also: Apple Cases iPhone 16: What Most People Get Wrong About Protection

What’s Actually Happening in the Core?

The fuel isn't a liquid. It's solid. We use ceramic pellets of uranium dioxide, roughly the size of a pencil eraser. These are stacked into long zirconium alloy tubes called fuel rods.

When a neutron hits a $U^{235}$ nucleus, things get messy. The nucleus becomes unstable, wobbles like a water balloon, and then snaps in two. This release of energy is what we’re after. It's not just heat; it's kinetic energy. The fission fragments fly apart, slamming into other atoms, and that friction generates the heat.

To keep it from turning into a meltdown, we use control rods. These are the "brakes" of the car. Made of materials like boron or cadmium, they love soaking up neutrons. Slide them in, and the reaction slows down because there aren't enough neutrons left to keep the chain going. Pull them out, and the "neutron flux" increases. It’s a delicate balance.

Nuclear engineers talk about "criticality." It sounds scary, like a "critical" medical condition, but in a reactor, being critical is the goal. It just means the reaction is self-sustaining. One neutron causes one fission, which releases one more neutron to cause the next fission. Perfectly steady.

The Plumbing Nightmare

Imagine the most complex radiator you’ve ever seen, then multiply it by a thousand. That is the primary coolant loop.

In a PWR, the water inside the nuclear reactor never actually touches the turbine. It’s way too radioactive for that. Instead, it stays in a closed loop. It gets incredibly hot—around 600 degrees Fahrenheit—but it doesn't boil because of that immense pressure I mentioned earlier. This hot, pressurized water travels to a steam generator, which acts like a heat exchanger.

It touches a second, separate loop of water. The heat transfers through the metal pipes, boiling the second loop of water into steam. That clean steam goes off to dance with the turbines.

This separation is why you can stand near the cooling towers of a nuclear plant and not grow a third arm. The stuff coming out of the top is just plain old water vapor. The "spicy" water stays locked away in the containment building.

Why We Don't Use "The Green Goo"

The myth of liquid green waste is mostly a holdover from 1950s sci-fi. Most high-level waste is just the spent fuel rods. When they come out of the reactor, they look exactly like they did when they went in—long metal tubes. They’re just much hotter and incredibly radioactive because they’re full of fission products like Cesium-137 and Strontium-90.

These rods go into "spent fuel pools," which are essentially massive swimming pools. Water is a fantastic radiation shield. You could technically swim in the top layer of a spent fuel pool and be perfectly fine, though the security guards would probably have some notes on your life choices.

The Safety Paradox

Here’s something most people get wrong: modern reactors are designed to fail "shut."

In the old Soviet RBMK designs (like Chernobyl), if the water disappeared or got too hot, the reaction could actually speed up. This is called a positive void coefficient. It’s a terrible idea. Modern Western reactors have a negative void coefficient. If the water boils away or the temperature spikes, the physical properties of the fuel and the water actually make it harder for the reaction to continue. The physics literally fights against a runaway reaction.

✨ Don't miss: Why That Walmart 55 Samsung TV Deal Is Usually Better Than It Looks

We also have "passive" safety systems now. In some newer designs, like the AP1000, they keep massive tanks of water above the reactor. If all the power goes out and the pumps stop, gravity just pulls that water down to keep the core cool. No electricity required. No human intervention needed.

Practical Insights for the Energy Conscious

If you’re trying to understand the future of the grid, keep these specific points in mind:

- Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): These are the "next big thing." Instead of building a massive, bespoke cathedral of power, companies like NuScale are building small, factory-made reactors that can be shipped on a truck. They are inherently safer because they have a much smaller "source term" (less radioactive material).

- Fuel Burnup: We are getting much better at using more of the energy in the fuel. Old reactors were like cars that ran out of gas with half a tank left. New fuel cycles are squeezing more "mileage" out of every uranium pellet.

- The Waste "Problem" is Political, Not Technical: We know how to store nuclear waste. We’ve been doing it in dry casks (massive concrete and steel cylinders) for decades without a single leak. The issue is finding a permanent geological home for it, which is more about "Not In My Backyard" than it is about engineering.

The reality inside the nuclear reactor is a triumph of thermodynamics over chaos. It’s the most complicated way to boil water ever devised, and yet, it provides about 20% of the electricity in the United States without puffing a single gram of CO2 into the atmosphere.

To stay informed on the actual progress of these technologies, watch the filings from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) or follow the research coming out of Idaho National Laboratory. They are the ones doing the actual "hot" testing on the next generation of fuels. Understanding the difference between a meltdown and a controlled shutdown is the first step in moving past the 1980s-era fear and into a realistic conversation about the 2026 energy landscape.

Start by looking at the "Generation IV" reactor designs. They operate at higher temperatures and lower pressures, using things like liquid salt or helium instead of water. That’s where the real engineering magic is happening right now.