You’ve seen the movies. Red lights flashing, a guy in a sweaty shirt screaming "SCRAM!" into a headset, and a massive digital countdown ticking toward zero. It's high drama. It’s also, for the most part, complete nonsense.

Step into a real nuclear reactor control room and the first thing you'll notice isn't the tension. It's the quiet. It’s the hum of high-efficiency HVAC systems and the soft clicking of mechanical switches. It feels more like a library or a high-end data center than a disaster movie set.

Basically, if things are going well, it’s actually kind of boring. And "boring" is exactly what nuclear operators get paid for.

The Anatomy of a Nuclear Reactor Control Room

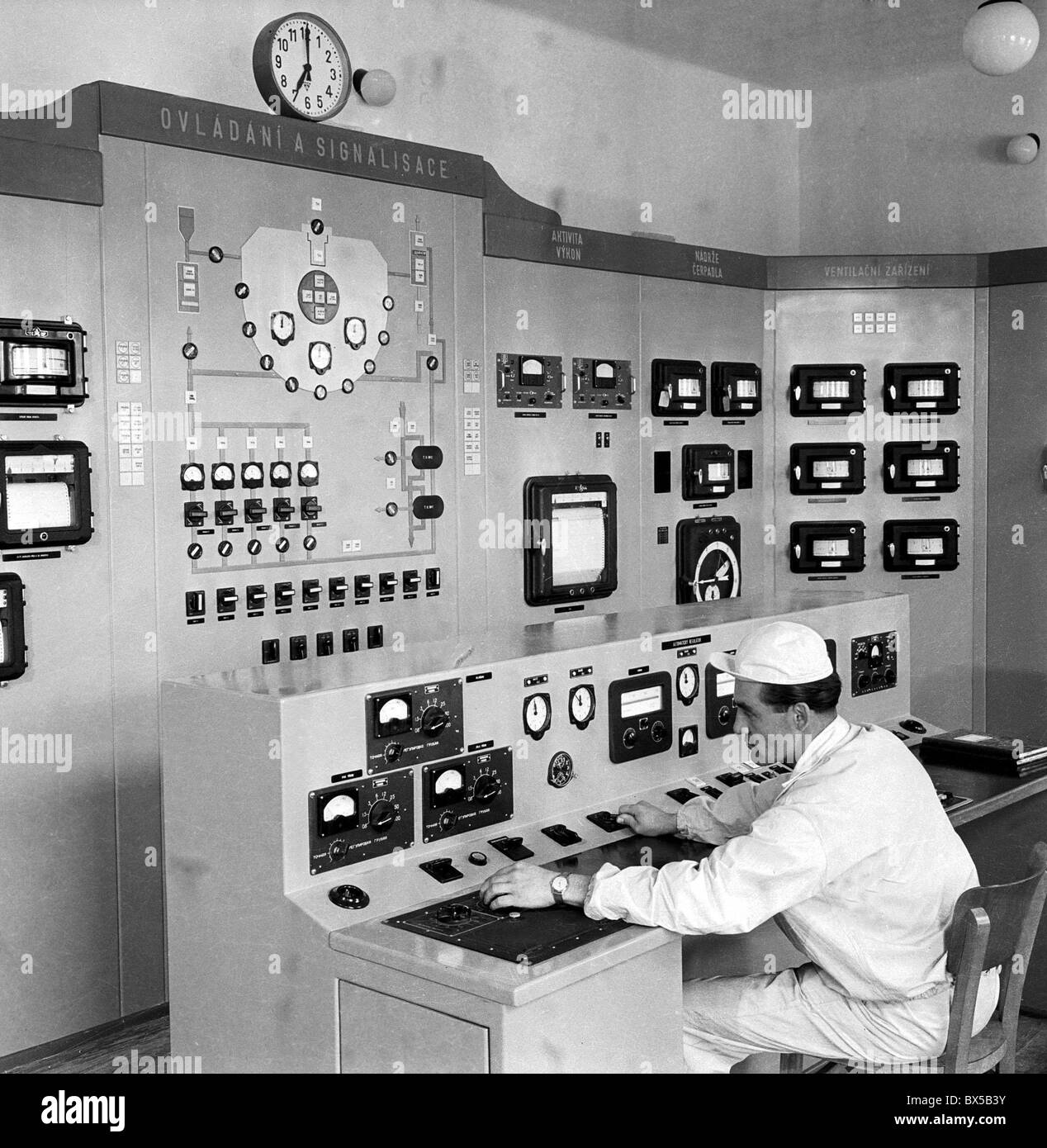

Most people think these places look like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise. In reality, the aesthetic depends entirely on when the plant was built. If you’re at a legacy plant like Peach Bottom in Pennsylvania, you’re looking at massive, wraparound green or grey steel panels covered in "dinosaur" tech—analog gauges, physical knobs, and those iconic light-up tiles called annunciator windows.

Newer designs, like the Westinghouse AP1000, look totally different. These are modern suites dominated by flat-screen displays and soft-touch keyboards. But regardless of the decade, the layout follows a very specific logic. You have the "Safety Parameter Display System" (SPDS) which gives the operators a high-level "health check" of the core at a single glance.

The room is usually partitioned. There’s the primary console where the Reactor Operator (RO) sits. Then there’s the Senior Reactor Operator (SRO) who stays a few steps back, acting as the "oversight" eyes. They don't touch the switches. They direct the person who does. This "eyes-on, hands-off" hierarchy is a psychological safeguard to prevent a single person from making a panicked mistake.

Why Everything is Twice (or Thrice) as Big

Everything in a nuclear reactor control room is redundant. If a sensor fails, there’s another one. If that one fails, there’s a third. This is what engineers call "defense in depth."

Take the water level in the pressure vessel. You aren't just looking at one needle. You’re looking at multiple independent channels of data. If Channel A says the water is low but Channels B and C say it’s fine, the operator knows they have a gauge problem, not a meltdown problem.

And then there are the "Soft Controls." In modern digital rooms, you don't just click a mouse. You usually have to perform a "select-before-operate" sequence. You click the valve on the screen, a confirmation box pops up, you verify it's the right one, and then you execute. It’s slow by design. Speed is the enemy of nuclear safety.

The "SCRAM" Mythos

You’ve heard the word. SCRAM. It stands for Safety Control Rod Axe Man—at least, that’s the legend from the Enrico Fermi days at the University of Chicago. Today, it’s officially called a "Reactor Trip."

💡 You might also like: Is Discord Down Right Now? Here’s What’s Actually Happening

When an operator hits that button (and yes, it’s usually a big, guarded physical switch), magnetic latches release the control rods. Gravity, or high-pressure nitrogen, shoves those rods into the core in about two seconds. The fission reaction stops almost instantly.

But here’s the thing: the heat doesn't just vanish. Even after a SCRAM, you have "decay heat." The control room’s main job for the next several hours is managing that residual heat. If you’ve read about the Fukushima Daiichi event, you know that the "trip" worked perfectly. The problem was the cooling systems that were supposed to run after the trip.

The Human Factor: 12 Hours of Focused Monotony

Who actually runs these things? It’s not just "guys in suits." Licensed operators go through years of training. To get an SRO license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), you have to spend hundreds of hours in a full-scale simulator.

These simulators are exact 1:1 replicas of the actual nuclear reactor control room. Every scratch on the desk, every flickering light, and every weirdly behaving gauge is mirrored. Why? Because in an emergency, muscle memory is everything. You need to know exactly where the Auxiliary Feedwater switch is without looking.

A typical shift is 12 hours. It involves a lot of "log-taking." They check the temperature of pump bearings. They monitor the chemistry of the primary coolant. They talk to the grid operators to see how much power the city needs.

The Three-Way Communication Rule

If you ever stand in a control room, the way people talk will sound weirdly robotic. That’s because of "Three-Way Communication."

- The SRO gives an order: "Operator, throttle back High Pressure Coolant Injection to 500 gallons per minute."

- The Operator repeats it back word-for-word: "Understood, throttling back HPCI to 500 gallons per minute."

- The SRO confirms: "That is correct."

It sounds tedious. It is. But it’s the reason why US commercial nuclear power has such a staggering safety record compared to almost any other heavy industry.

Digital vs. Analog: The Great Debate

There is a massive debate in the industry right now about "Digital Upgrades." You’d think newer is better, right? Not necessarily.

🔗 Read more: Google Earth on the Moon: How to Actually Explore the Lunar Surface Today

Analog systems are "dumb," which makes them incredibly robust. A physical wire connecting a sensor to a needle can't be hacked. It doesn't have software bugs. It doesn't "lag."

Digital systems, however, offer much better diagnostic data. They can predict a pump failure weeks before it happens. The challenge is "Common Cause Failure." If a software bug exists in the operating system of the control room, it could theoretically affect everything at once. This is why plants like Darlington in Canada or the newer units at Vogtle in Georgia spend millions of dollars on "Cyber Security Assessments" and "Software Verification."

What Happens During a "Transient"?

In the industry, a "transient" is anything that isn't steady-state operation. Maybe a turbine trips because a bird hit a transformer outside. Maybe a pipe develops a small leak.

When this happens, the nuclear reactor control room transforms. It doesn't get loud, but the "Annunciator" tiles start dark-flashing and a chime sounds.

The operators immediately pull out "EOPs"—Emergency Operating Procedures. These are thick, laminated binders (or digital equivalents) that use flowcharts. "If Pressure > 1000 PSI, go to Step 4. If Pressure < 1000 PSI, go to Step 9."

There is no "freestyling." You follow the book. The book has been vetted by thousands of engineers and tested in simulators for every conceivable scenario, including "Black Swan" events.

Real-World Nuance: The TMI-2 Lesson

We can't talk about control rooms without mentioning Three Mile Island. In 1979, the operators were overwhelmed by over 100 different alarms going off at once. It was "information overload."

One specific light in the control room indicated that a signal had been sent to close a valve, but it didn't actually confirm the valve was closed. The operators thought it was shut; it was actually wide open, spilling coolant.

This disaster changed the nuclear reactor control room forever. It led to the creation of the "Human Factors Engineering" discipline. Today, control boards are designed so that the most important gauges are right at eye level, and "mimic" displays show a literal map of the pipes so you can see exactly where the water is flowing.

Actionable Insights for the Tech-Curious

If you're fascinated by the intersection of human psychology and high-stakes engineering, there are ways to see this world without a security clearance.

- Visit a Training Center: Many nuclear plants have "Energy Education Centers" nearby. Some even have public viewing galleries for their simulators.

- Study Human Factors: If you're a UI/UX designer, look into "NUREG-0700." It’s the NRC’s massive guidebook on how to design control rooms. It’s a masterclass in preventing human error through design.

- Monitor the Daily Status: The NRC publishes a "Power Reactor Status Report" every single morning. You can see exactly which reactors are at 100% power and which ones are "down" for maintenance or trips. It’s a raw look at the heartbeat of the grid.

- Check Out Virtual Tours: Organizations like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) often post 360-degree tours of various reactor designs, including the high-tech control rooms of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

The control room is the brain of the plant. It’s a place where "boring" is the ultimate goal, and where every single switch has a story, a backup, and a procedure. It’s not about the drama of the meltdown; it’s about the incredible, quiet discipline required to make sure one never happens.

If you want to understand the future of energy, stop looking at the cooling towers. Look at the consoles. That’s where the real work happens.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To understand the practical application of these systems, research the Human-System Interface (HSI) design of the NuScale Power Module. It represents the next generation of control room philosophy, where a single operator might manage up to 12 small reactors simultaneously using advanced automation. Also, look into the OECD Halden Reactor Project, which has spent decades researching how operators behave under stress in these specific environments.