The Kea Channel is a moody stretch of water. It sits off the coast of Greece, specifically the island of Kea, and beneath its surface lies a monster. Most people know the Titanic, obviously. They’ve seen the movie; they know the iceberg. But fewer people realize that the Titanic had a younger, bigger, and arguably more tragic sister named the HMHS Britannic. She’s been sitting on the seafloor for over a century, and honestly, what explorers find inside the Britannic wreck today is way more haunting than anything you’ll see in a Hollywood blockbuster.

She’s massive. At 882 feet, she actually outclassed the Titanic in terms of safety features. After the 1912 disaster, Harland and Wolff went back to the drawing board to make the Britannic "unsinkable" for real this time. Double hulls. Higher bulkheads. Giant crane-like davits for lifeboats. It didn't matter. In 1916, while serving as a hospital ship during World War I, she hit a mine. She sank in 55 minutes. That’s three times faster than her sister.

The chaotic reality of the debris field

Walking—or rather, swimming—through the site isn't like a museum tour. It's a mess. Because the ship hit the bottom while the bow was still rising, the front of the vessel is actually bent and mangled from the impact. It’s weird to think about a steel giant of that magnitude snapping like a twig, but the physics of a 50,000-ton ship hitting the seabed are brutal.

When divers like Richie Kohler or Bill Smith descend the 400 feet to reach her, they aren't just looking at a ship. They're looking at a 20th-century trauma site. The depth is the first hurdle. This isn't a casual recreational dive. You’re looking at technical diving involving trimix—a blend of helium, nitrogen, and oxygen—to prevent nitrogen narcosis. If you mess up your gas mix, you’re dead before you even see the hull.

Inside the Britannic wreck, things get even more claustrophobic. The ship is lying on her starboard side. This means everything is rotated 90 degrees. Floors are now walls. Doors are now hatches in the ceiling. It messes with your internal compass. Imagine trying to navigate a hospital corridor where the floor is vertical and the "room" you’re trying to enter is a dark, silt-filled void to your left.

✨ Don't miss: Orlando Disney World Pictures: Why Yours Look Different Than the Pro Shots

Tiles, toilets, and the ghost of a grand staircase

One of the most striking things explorers report is the preservation of the floor tiles. In the first-class areas, you can still see the intricate patterns of the linoleum and ceramic. It’s bright. It’s colorful. It’s completely out of place in a graveyard.

- The "Silent Room": There are sections of the ship where the silt hasn't settled heavily. Here, you see brass fixtures still polished by the salt water, looking almost new.

- Medical Remnants: Since she was a hospital ship, the interior is cluttered with iron bed frames and medical cabinets.

- The Organ: There’s a famous story about the pipe organ meant for the Britannic. It never made it on board because of the war, but the space where it was supposed to go remains a hollow, eerie cavern.

The Grand Staircase is gone. Unlike the Titanic, where the wood floated away and left a clear shaft for ROVs to descend, the Britannic’s staircase area is a jumbled wreck of fallen steel and debris. You can’t just fly a drone down the middle. You have to weave through "the jungle," which is what some divers call the mess of wires and pipes hanging from the overheads.

Why the ship is staying remarkably intact

You’d think a hundred years in the Mediterranean would turn the ship to dust. Nope.

The water temperature and chemistry near Kea are different from the North Atlantic. There are fewer "rusticles"—those iron-eating bacteria colonies that are currently devouring the Titanic. The Britannic is surprisingly sturdy. The paint is still visible in spots. You can read the name on the hull if you scrape away enough sea growth.

However, "sturdy" is a relative term. The weight of the ship resting on its side is slowly crushing the lower decks. Dr. Robert Ballard, who discovered the wreck in 1975 (yes, the same guy who found Titanic), noted that the structure is under immense stress.

The interior is also a maze of silt. One wrong kick of a fin and the "viz" (visibility) goes to zero. It’s called a "silt-out." If you’re deep inside the boiler rooms or the engine room when that happens, you’re basically blind. You have to feel your way out along a guide line, hoping you don't snag your tanks on a jagged piece of 1910s steel.

The mystery of the open portholes

Here is the thing that really bothers historians. When the Britannic was sinking, the Captain tried to beach the ship on Kea. Because the ship was moving, water was forced into the hull much faster. But there was another problem: the portholes.

It was a hot morning. The nurses had opened the portholes to ventilate the wards. When the ship listed, those open windows acted like hundreds of little hoses, sucking water into the "watertight" compartments.

When you look inside the Britannic wreck today, you can see these portholes. Some are still open. It’s a haunting reminder of a simple human decision—wanting a breeze—that probably doomed the ship.

The engine room: A mechanical cathedral

For the gearheads, the engine room is the holy grail. The Britannic used massive reciprocating engines and a low-pressure turbine. Because the ship sank in relatively shallow water (compared to 12,000 feet for Titanic), these engines didn't implode.

They are standing there, four stories tall, covered in a thin layer of silt and sea life. They look like they could almost turn over if you gave them a nudge. The scale is impossible to describe. A human diver looks like a tiny speck next to the connecting rods.

📖 Related: I-95 Traffic Report: Why Your GPS Is Lying and How to Actually Beat the Gridlock

It’s quiet down there. Terrifyingly quiet.

The ethics of the interior

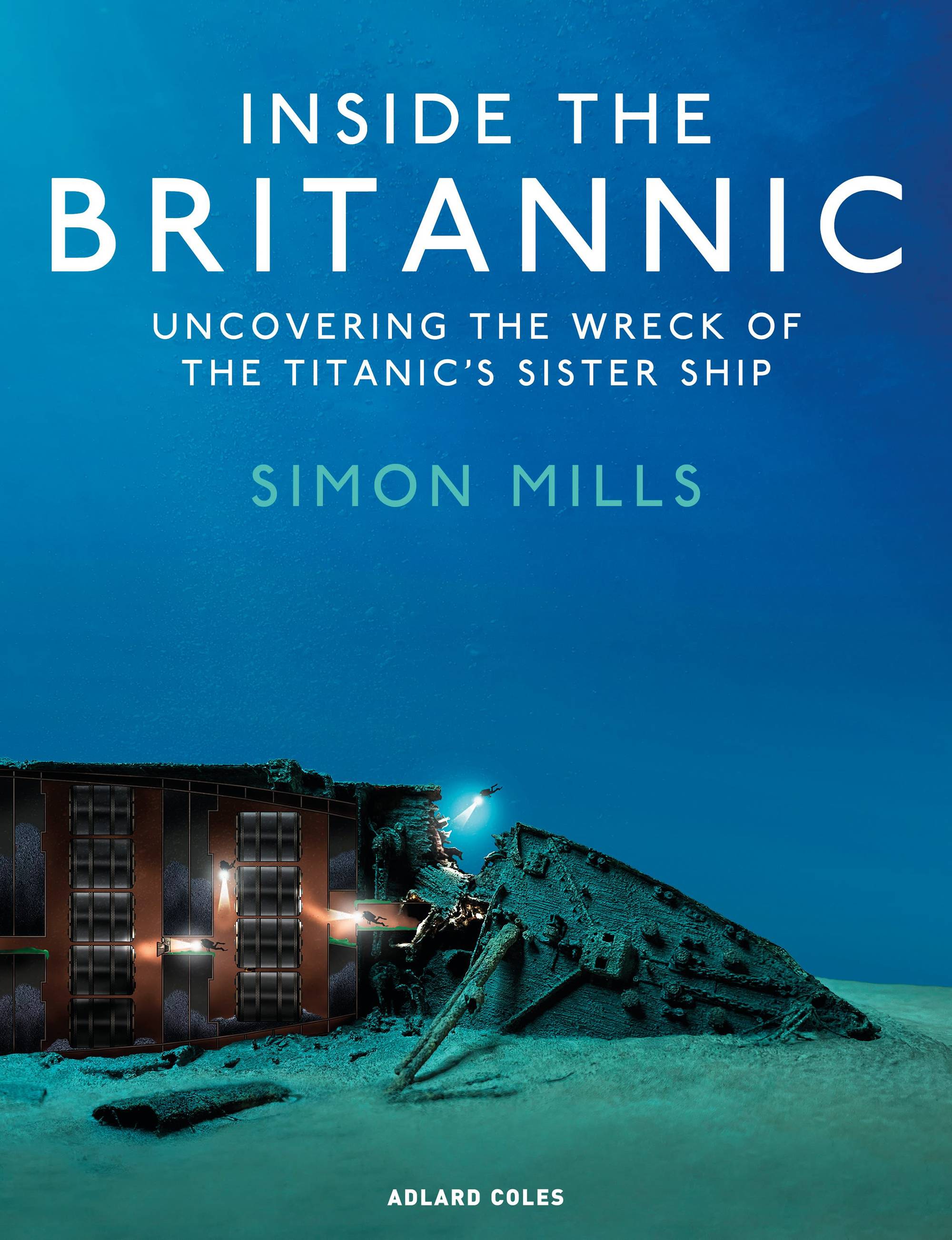

There is a huge debate about who gets to go inside. The wreck is owned by Simon Mills, a British maritime historian who bought it from the UK government in the 90s. He’s been a fierce advocate for its preservation.

The Greek government also treats it as a war grave. You can’t just show up with a boat and a scuba tank. You need permits, a mountain of insurance, and a legitimate scientific or cinematographic reason to be there.

There are still bodies in there. Or, more accurately, the remains of the 30 people who died. Most of them were killed when their lifeboats were sucked into the still-turning propellers while the ship was trying to make its run for the shore. It’s a grim thought, but those propellers—massive bronze blades—are still there, partially buried in the sand, frozen in the act of destruction.

What we’re still learning

Recent expeditions using 3D photogrammetry are changing how we see the interior. Instead of grainy, green-tinted video, we now have high-resolution digital models.

We’ve learned that the mine hit near the coal bunkers. We’ve learned that the fire doors didn't all close properly, likely due to the ship's frame warping instantly from the blast. This is "forensic shipwreck analysis." It’s less about treasure hunting and more about solving a 110-year-old cold case.

Every time a diver enters a new cabin, they find something. A washbasin. A light switch. A stack of plates. These objects aren't just "stuff"; they are the last things people touched before they ran for their lives.

Navigating the legal and physical dangers

If you’re thinking about the Britannic, you have to respect the depth. 120 meters is a long way down.

- The Gas: You’re breathing a cocktail that costs thousands of dollars just to mix.

- The Current: The Kea Channel has ripping currents that can pull a diver off the wreck and into the open sea in seconds.

- The Entanglement: Fishing nets are draped over parts of the ship like spiderwebs. They are invisible until you’re stuck.

For most of us, the closest we’ll get to going inside the Britannic wreck is through the lens of explorers like Evan Kovacs or the legendary Jacques Cousteau, who first explored her in the 70s.

Actionable insights for shipwreck enthusiasts

If this kind of history fascinates you, don't just watch the movies. Here is how to actually engage with the history of the Britannic:

✨ Don't miss: Why Huntington Lake Fresno CA Stays Cool While the Valley Scorches

- Study the Deck Plans: You can find the original Harland and Wolff blueprints online. Comparing these to dive footage helps you understand just how much the ship deformed during the sinking.

- Visit the Kea Museum: If you ever travel to Greece, the local islanders have a deep connection to the wreck. There are small exhibits dedicated to the disaster.

- Support Virtual Preservation: Follow projects like the "Britannic 100" or organizations that use LIDAR scanning. This is the only way the ship will "live" once the steel finally gives way.

- Read "The Unseen Britannic": Simon Mills has written extensively on the ship's history. It’s the definitive source for anyone who wants to move past the Titanic comparisons and understand this ship on its own merits.

The Britannic isn't just a "failed sister." She was a ship of mercy, a hospital at sea, and a marvel of engineering that met an impossible end. Seeing the world inside her hull is a reminder of how quickly "unsinkable" becomes a memory.