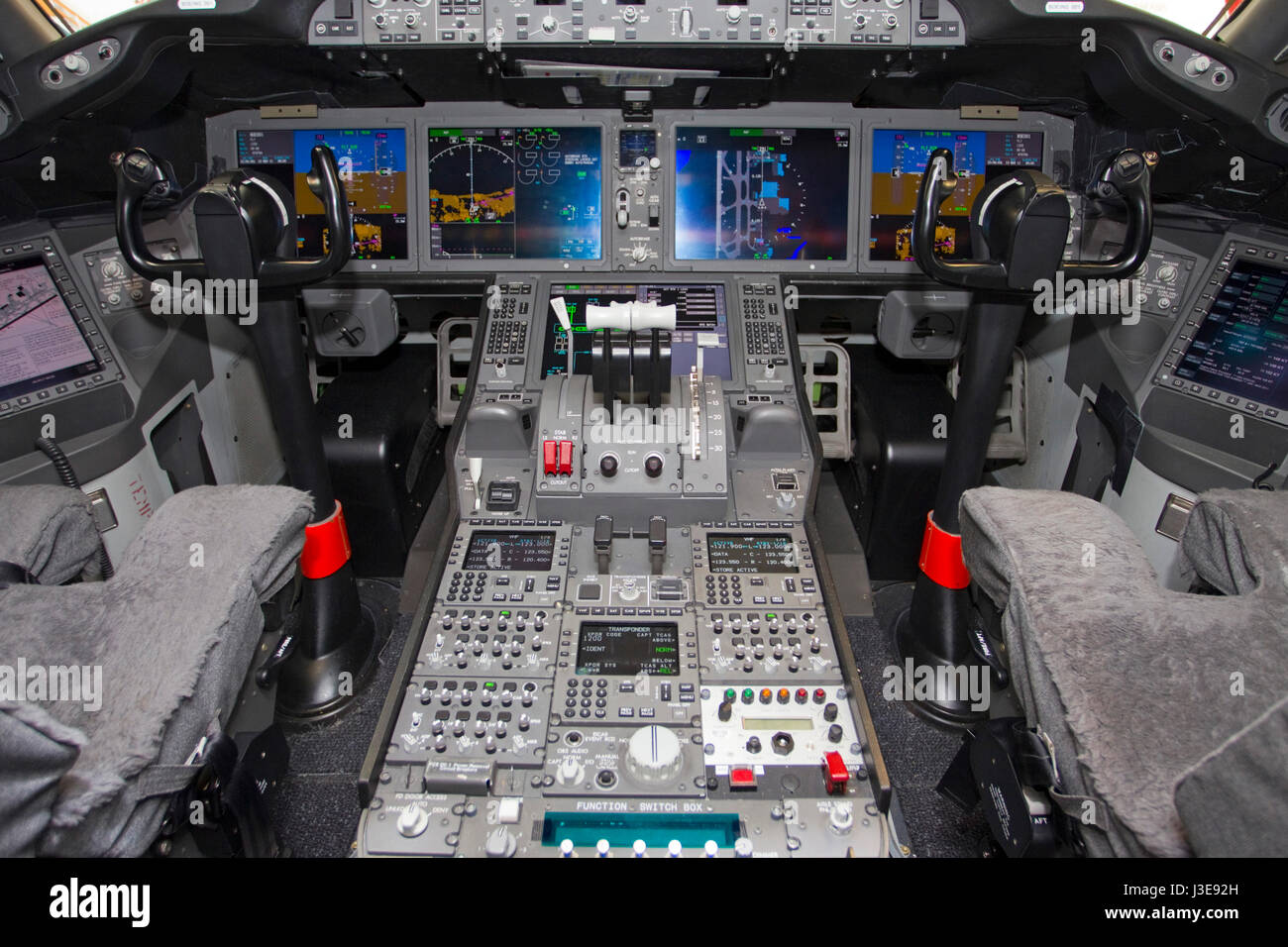

Walking into the front office of a Dreamliner feels less like entering a traditional airplane and more like stepping into a high-end Silicon Valley workstation. It's quiet. Almost eerie. If you’ve spent any time in an old 737 or an MD-80, the first thing you notice about the cockpit of Boeing 787 is the sheer lack of "clutter." There aren't hundreds of dedicated circular gauges staring back at you with flickering needles. Instead, you're met with massive, high-definition glass screens that look like they belong in a Tesla, only with much higher stakes.

Boeing didn’t just iterate here; they pivoted.

The philosophy shifted from "give the pilot every bit of data all the time" to "show the pilot what they need, exactly when they need it." It’s called quiet dark philosophy. If a system is running normally, it doesn't shout at you. No lights. No warnings. Just a calm, dark environment that allows the crew to focus on the horizon. This isn't just for aesthetics. It’s a direct response to pilot fatigue, a silent killer in long-haul aviation that the 787 was specifically designed to conquer.

The HUD is No Longer an Option

In most planes, the Head-Up Display (HUD) is a pricey add-on. For the cockpit of Boeing 787, it’s standard equipment. You’ve got these two clear glass panes that drop down from the ceiling in front of both the Captain and the First Officer.

These aren't just for looking cool. They project critical flight data—airspeed, altitude, horizon line—directly into the pilot's line of sight. Imagine landing in heavy fog at Heathrow. Instead of constantly glancing down at the instrument panel and then back up at the runway, the pilot stays "eyes out." It creates a seamless transition from instrument flying to visual flying. Honestly, once pilots get used to the 787’s HUD, they usually hate going back to planes without them. It’s like trying to drive a car with no side mirrors after you've had them your whole life.

Why Five Screens Are Better Than Fifty

The heart of the flight deck consists of five massive 15.1-inch LCDs. They’re arranged in a T-shape. What’s wild is that these screens are completely reconfigurable. If the center screen fails, the data just hops over to another one.

- The outboard screens usually handle the Primary Flight Display (PFD).

- The inner screens show the Navigation Display (ND).

- The big center screen acts as the Multi-Function Display (MFD).

But here’s the kicker: the pilots use a "cursor control device" (basically a ruggedized trackball) to navigate these screens. It feels very "point and click." You can pull up electronic checklists, check the health of the Trent 1000 engines, or zoom in on a weather cell over the Atlantic with a flick of the thumb.

📖 Related: Apple iPhone 11 64GB: Why This Budget Workhorse Still Makes Sense Today

The Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) is integrated directly into the side consoles too. In the old days, pilots lugged around heavy "brain bags" full of paper charts. Now? It’s all digital. Jeppesen charts are built right into the glass. This saves weight, which saves fuel, which is the whole point of the 787 anyway.

The Fly-By-Wire Secret

The 787 is a fly-by-wire aircraft, but Boeing kept the yokes. This is a huge point of contention among aviation geeks. Airbus uses side-sticks, which looks very futuristic. Boeing stuck with the traditional control column between the pilot's legs.

Why? Because Boeing believes in tactile feedback.

Even though there are no physical cables connecting that yoke to the ailerons, the plane uses "active feel" technology. If you try to pull a maneuver that puts the plane at risk, the yoke fights you. It provides artificial resistance. This keeps the "seat of the pants" feel alive in an era of digital code. Captain Ken Hoke, a veteran long-haul pilot, has often noted that this tactile connection helps maintain situational awareness when things get hairy. It’s that human-machine interface that Boeing obsesses over.

Common Misconceptions About the 787 Flight Deck

A lot of people think the 787 is "fully automated" and the pilots are just there for the ride. That’s nonsense.

📖 Related: Ford and the Assembly Line: What Most People Get Wrong About the 1913 Revolution

While the cockpit of Boeing 787 features incredible automation, it’s there to manage complexity, not replace judgment. For instance, the Vertical Situation Display (VSD) shows a side profile of the plane's flight path. It shows you the mountains and the terrain relative to your descent path. It doesn't fly the plane over the mountain for you; it gives you the visual data to ensure you don't hit it.

Another myth is that it's "too quiet." While the flight deck is significantly quieter than a 747 because of the sawtooth engine nacelles and better insulation, pilots still rely on aural cues. You need to hear the wind. You need to hear the gear drop. The 787 balances this by using digital sound synthesis to provide certain "feedback" noises that would otherwise be lost in the super-insulated cabin.

The Systems You Can't See

Under the floorboards of the cockpit lies the Common Core System (CCS). Think of this as the plane's nervous system. In older jets, every system—the air conditioning, the lights, the brakes—had its own computer. In the 787, GE Aviation developed a centralized "brain" that handles almost everything.

This saves miles of wiring.

Literally.

The reduction in wiring alone contributes to the 20% fuel savings the Dreamliner boasts over its predecessors. It’s also incredibly redundant. If one "cabinet" of the CCS fails, the other takes over instantly. You won't even see a flicker on the cockpit displays.

The Human Element: Lighting and Humidity

The cockpit isn't just about dials; it's about biology. The 787 is pressurized to 6,000 feet rather than the standard 8,000. This might sound like a small change, but for a pilot doing a 14-hour trek from Perth to London, it’s a game-changer. More oxygen in the blood means faster reaction times and fewer headaches.

[Image comparing 6,000 ft vs 8,000 ft cabin altitude effects on the human body]

The LED lighting in the cockpit is also tuned to the human circadian rhythm. During a night flight, the displays shift in color temperature to reduce blue light exposure. It’s basically "Night Shift" mode for an airliner. This helps pilots stay alert during the "window of circadian low" (that 3:00 AM slump where the brain just wants to shut down).

What’s Next for the 787 Flight Deck?

Boeing is already looking at the 787-10 and beyond. There are talks about further integrating synthetic vision systems (SVS), which would turn those HUDs into a "video game" view of the world, even in total darkness. Imagine looking through a cloud and seeing a computer-generated 3D wireframe of the runway.

We aren't there yet for every airline, but the hardware is ready.

The 787 was the first "more electric" airplane. It replaced bulky hydraulic systems with electric starters and compressors. This means the cockpit has fewer "steam gauges" for hydraulic pressure and more status bars for electrical loads. It’s a cleaner, more reliable way to fly.

Practical Insights for Aviation Enthusiasts

If you’re a flight simmer or a student pilot looking at the 787, here are the key things to master:

- Master the FMC: The Flight Management Computer is the heart of the 787. You don't "fly" this plane; you manage its trajectory.

- Trust the HUD: Don't look down. Learn to fly the symbols on the glass. It makes your landings 10x smoother.

- Understand the "Checklist" Button: The 787 has electronic checklists that actually "sense" if you’ve completed a task. If you flip a switch, the item turns green on the screen automatically.

- Watch the Electrical Synoptics: Since this is an electric-heavy plane, knowing where your power is coming from (Engine Gen, APU, or Battery) is more important here than in a 777.

The cockpit of Boeing 787 represents the peak of 21st-century aeronautical engineering. It’s a workplace designed to keep humans at their best by removing the "noise" of the machine. Whether you're a passenger or an aspiring aviator, understanding this flight deck gives you a glimpse into how we’ve conquered the most grueling long-haul routes on the planet.

To further your understanding, look into the specific differences between the GEnx and Trent 1000 engine display variants, as the cockpit software adjusts slightly depending on which power plant the airline has chosen. You should also study the "Point-and-Click" interface logic, as this is the standard for all future Boeing widebodies, including the upcoming 777X.