Ever looked at a textbook and seen those neat, colorful slices of a mountain? They make it look so simple. Red line goes up, triangle goes boom. But honestly, if you actually saw an inside a volcano diagram that was 100% realistic, it would look like a chaotic, messy plumbing nightmare designed by a subterranean plumber who’d lost their mind.

Volcanoes aren't just hollow cones filled with soup.

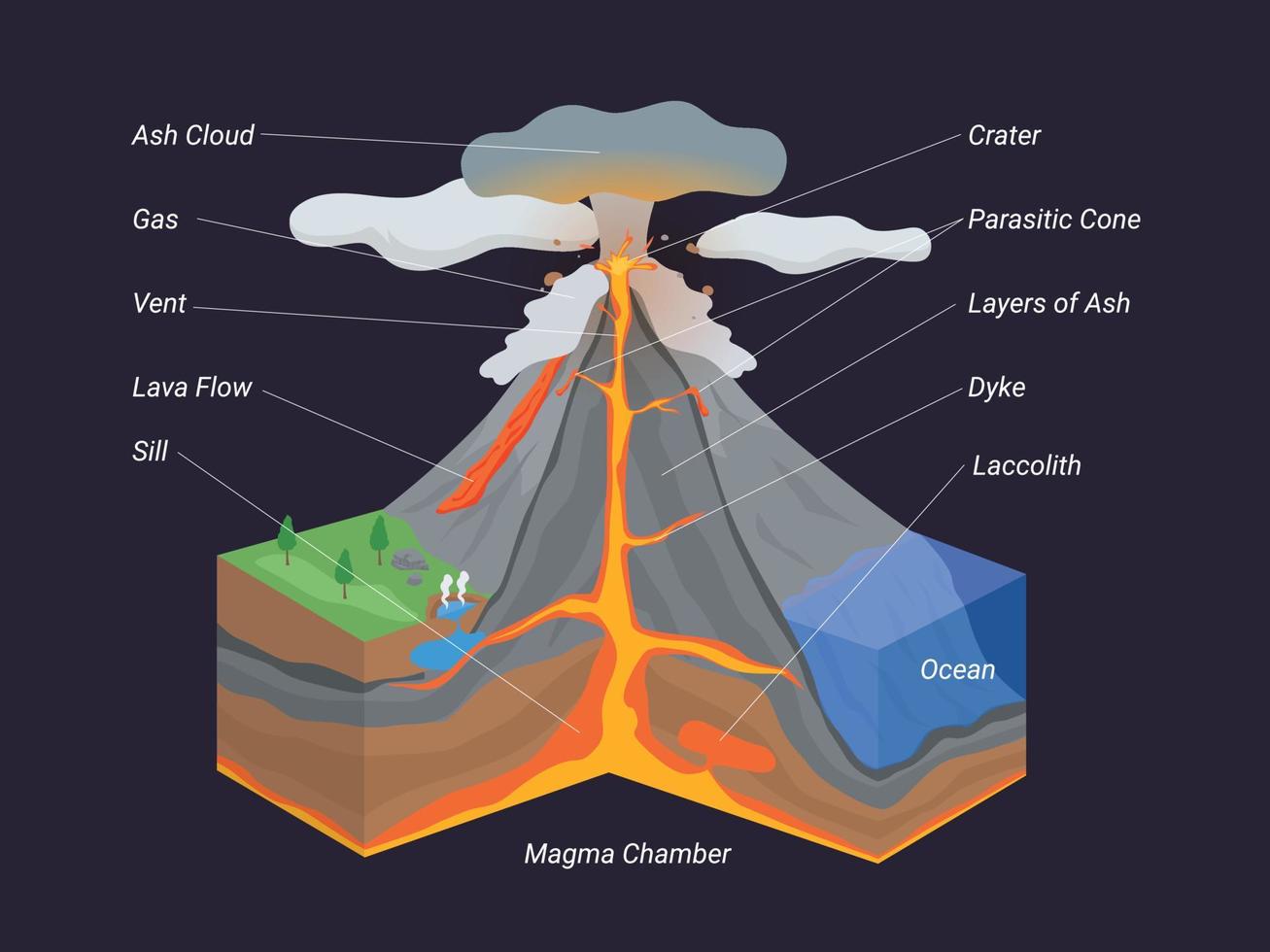

They are complex geological engines. Below the surface, we’re talking about high-pressure physics, chemical reactions that change the density of rock, and a plumbing system that would put a skyscraper to shame. Most diagrams show a single "main vent" shooting straight up. Real life? It’s rarely that tidy. Magma finds the path of least resistance. Sometimes that’s the top. Often, it’s a crack in the side that turns into a parasitic cone, or a horizontal sheet that never even breaks the surface.

The Magma Chamber is Not a Giant Balloon

When you look at an inside a volcano diagram, the first thing that catches your eye is usually that big red bulb at the bottom labeled "magma chamber." We’ve been conditioned to think of it as a huge, underground lake of liquid fire. It isn't. Not really.

Geologists like those at the USGS describe it more like a "mush zone." Think of a sponge. It’s a region of rock that is partially melted—crystals, gas bubbles, and liquid magma all jammed together under terrifying amounts of pressure. It’s more solid than liquid most of the time. When new, hotter magma rises from the mantle, it "recharges" this mush, heating it up until the pressure becomes too much for the overlying rock to hold back.

The Plumbing: Conduits and Sills

Magma is lazy. If it can find a pre-existing crack or a weak layer of sedimentary rock to squeeze into, it will. In a standard inside a volcano diagram, you’ll see the "conduit" or "pipe." This is the primary highway. But look closer at more advanced geological maps and you'll see dikes and sills.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Dikes are the vertical intruders. They cut across rock layers like a knife. Sills are horizontal, squeezing between layers like jam in a layer cake. Sometimes, a sill gets so much pressure behind it that it bows the ground upward, creating a "laccolith." You might be standing on a volcano's plumbing right now and never know it because the magma decided to travel sideways instead of up.

Gas: The Real Engine of Destruction

Why do some volcanoes just ooze lava while others blow their tops off? It’s the gas. Specifically water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide.

In an inside a volcano diagram, gas is hard to draw. But it’s the most important factor. Imagine a bottle of soda. When the cap is on, you don't see the bubbles because the pressure keeps them dissolved in the liquid. As magma rises through the conduit, the pressure drops. Suddenly, those dissolved gases turn into bubbles.

If the magma is "runny" (low viscosity, like the basalt at Kilauea), the bubbles can escape easily. The result? A gentle fountain of lava. But if the magma is thick and sticky (high viscosity, like the dacite at Mt. St. Helens), the bubbles get trapped. The pressure builds and builds until—pop. The entire mountain literally disintegrates. This is why the "throat" of the volcano in your diagram is such a high-stakes environment. If it gets plugged by a hardened lava dome, you’re looking at a ticking time bomb.

The Layers of the Cone

Look at the walls of the volcano in the diagram. You'll notice they are striped. This is the hallmark of a "stratovolcano" or composite volcano. These are the classic "pretty" mountains like Mt. Fuji or Mt. Rainier.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Those layers are a history book of violence.

- Lava Flows: The solid, rocky layers from "quiet" eruptions.

- Tephra and Ash: The crumbly, loose layers from explosive eruptions.

- Pyroclastic Flow Deposits: The remnants of superheated clouds of ash and gas that scream down the mountain at 100 miles per hour.

It’s a cycle. Erupt, layer, erode, repeat. Over hundreds of thousands of years, these layers build the massive structures we see today.

What's Actually Happening at the Crater?

The very top of your inside a volcano diagram usually shows a crater. But there’s a massive difference between a crater and a caldera, and people mix them up all the time.

A crater is a small, funnel-shaped pit formed by the explosive venting of gas and lava. A caldera, on the other hand, is what happens when the "mush zone" we talked about earlier empties out so fast that the roof collapses. The mountain literally falls into itself. Crater Lake in Oregon is the gold standard for this. It’s not a crater; it’s a 1,900-foot-deep hole where a 12,000-foot mountain used to be.

The Unseen Components: Fumaroles and Water Tables

If you want a truly accurate inside a volcano diagram, you have to look at the stuff that isn't glowing red.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Fumaroles are vents that emit only steam and volcanic gases. They are the "exhaust pipes" of the system. Then there's the interaction with groundwater. When magma gets close to the water table, things get spicy. This creates "phreatic" eruptions—basically steam explosions. No new magma reaches the surface, but the mountain still blows apart because the water turned to steam instantly. This is what happened at Ontake in Japan in 2014. It’s a reminder that even a "quiet" volcano is a chemical factory working overtime.

Beyond the Diagram: The Life Cycle of a Giant

Volcanoes aren't permanent. They are born, they grow, and eventually, they die or go "extinct." But "extinct" is a dangerous word in geology. We used to think some volcanoes were dead just because they hadn't erupted in human memory. Then we discovered that some systems can stay quiet for 500,000 years and then suddenly wake up.

An inside a volcano diagram for an extinct volcano would show a "plug" or "neck." This is the hardened magma that stayed in the conduit after the last eruption. Over millions of years, the soft outer layers of the mountain erode away, leaving just the hard plug standing alone. Shiprock in New Mexico is a perfect example. It's the "skeleton" of a volcano.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you are looking at an inside a volcano diagram for a school project, a hobby, or because you’re a bit of a geology nerd, remember that the map is not the territory.

- Check the Type: Is it a Shield volcano (flat and wide), a Stratovolcano (tall and pointy), or a Cinder Cone (small and gravelly)? The internal structure changes completely based on the magma's chemistry.

- Look for the Heat Source: Is it a "hotspot" (like Hawaii) or a subduction zone (like the Andes)? This tells you where the magma is coming from—the deep mantle or the melting of a tectonic plate.

- Trace the Path: Don't just look at the center. Look for the side vents and sills. That's where the real "surprises" happen during an eruption.

The next time you see a diagram of a volcano, don't just see a mountain. See a pressurized, chemical-rich, multi-layered system that is constantly trying to find a way to the surface. It’s a living part of the Earth’s cooling process.

To get the most out of your study, compare a cross-section of a basaltic shield volcano with a rhyolitic caldera. The difference in the size and shape of the magma reservoirs will tell you everything you need to know about why one is a tourist attraction and the other is a global threat. Search for high-resolution bathymetry or seismic tomography images if you want to see what these "chambers" actually look like in 3D—it’s much more like a tree root system than a simple bowl.