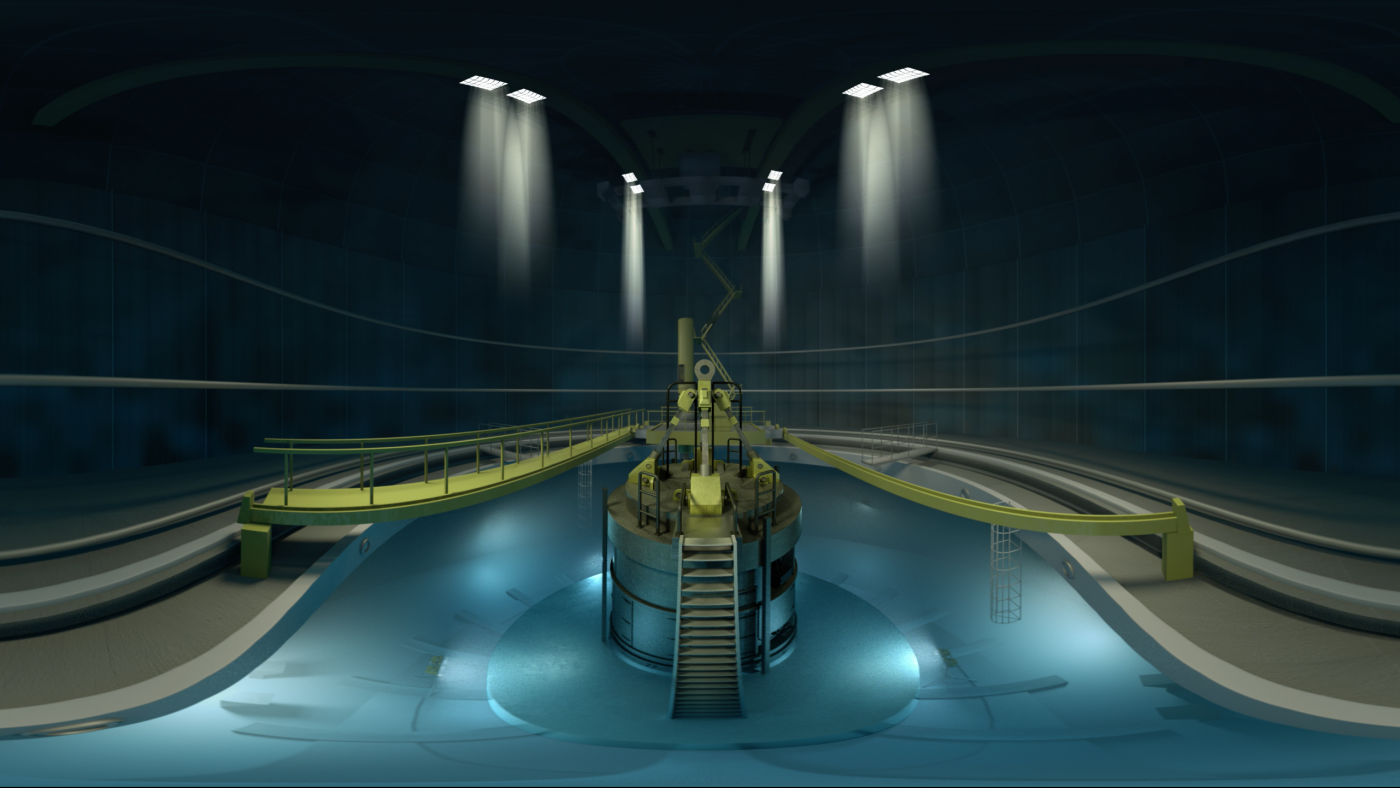

Most people imagine a glowing green liquid or a ticking time bomb when they think about being inside a nuclear reactor. Honestly? It’s nothing like the movies. It is quieter, cleaner, and way more blue than you’d expect. If you stood on the walkway above an open pool reactor, you wouldn't see smoke or fire. You’d see a deep, shimmering sapphire glow emanating from the water. That’s Cherenkov radiation. It happens when electrically charged particles, like electrons, move through the water faster than the speed of light in that specific medium. It’s the visual "sonic boom" of the subatomic world.

The heart of the machine is a study in extreme engineering. We are talking about a system designed to contain a controlled chain reaction that generates millions of watts of thermal energy. But it’s not just about the heat; it’s about the balance. If you've ever wondered how we keep a sun-like energy source from melting through the floor, the answer lies in a very precise dance between fuel, moderators, and cooling systems.

The weird physics of the reactor core

Step into the containment building and the first thing you notice is the scale. The walls are thick. Often, you’re looking at four feet of steel-reinforced concrete. This isn't just for show; it’s the final line of defense. Inside that shell sits the reactor vessel, a massive steel "pot" that holds the fuel assemblies.

What’s actually happening inside those assemblies?

Basically, it's a game of atomic billiards. You have Uranium-235 atoms. When a stray neutron hits a U-235 nucleus, the nucleus becomes unstable and splits. This is fission. When it splits, it releases a massive amount of kinetic energy—which turns into heat—and a few more neutrons. Those neutrons then go off to hit other atoms. If you have enough U-235 packed together (what we call "critical mass"), the reaction becomes self-sustaining.

But there’s a catch. Neutrons released from fission are moving way too fast. They’re like caffeinated toddlers; they just bounce off things without doing much work. To make them useful, we have to slow them down. This is where the moderator comes in. In most American reactors, like the Pressurized Water Reactors (PWR) used at plants like Palo Verde in Arizona, the moderator is just regular old water. The water molecules "bump" into the neutrons, absorbing their energy and slowing them down until they are "thermal" neutrons, which are much better at causing more fission.

Control rods are the brakes of the system

If the water is the stage, the control rods are the conductors. You’ll see these long, silver-colored rods made of materials like boron, cadmium, or hafnium. These elements are "neutron sponges." They love soaking up neutrons.

If the reactor starts getting too hot or the reaction rate climbs too high, the operators (or the automated systems) lower these rods into the core.

- Rods go in? Neutrons get absorbed.

- The chain reaction slows down.

- Rods come out? More neutrons are free to hit uranium.

- The power goes up.

It is a remarkably simple mechanical solution to a complex quantum problem. In an emergency, a "SCRAM" occurs. This is a sudden, gravity-driven or hydraulic drop of all control rods into the core at once. It shuts down the fission process in roughly two seconds. People often ask if a reactor can explode like a nuclear bomb. The short answer is no. The fuel enrichment in a commercial reactor—usually around 3% to 5% U-235—is nowhere near the 90% required for an explosion. It physically cannot happen. It can melt, sure, but it won't go mushroom cloud.

🔗 Read more: Inside Reactor 4 Chernobyl: What It Actually Looks Like Today

Why the water doesn't just boil away

You might think that putting a 600-degree Fahrenheit heat source in water would lead to a massive steam explosion instantly. In a Pressurized Water Reactor, we prevent this by keeping the water under immense pressure—about 2,250 pounds per square inch (psi). Because the pressure is so high, the water stays liquid even though it’s way past its normal boiling point.

This "primary loop" water is radioactive because it’s been sitting right next to the fuel. To actually turn a turbine, this hot water travels through a heat exchanger. It heats up a second loop of water that is under much lower pressure. This second loop turns into steam, spins the big blades of the turbine, and makes the electricity that charges your phone.

The two loops never touch.

This is a crucial detail. It’s why the steam you see coming out of the iconic "hourglass" cooling towers at a nuclear plant is actually just pure, clean water vapor. It’s never been near the radiation.

The fuel pellets: Small but mighty

Inside the reactor, the fuel itself doesn't look like much. It’s not glowing rods of green goo. It’s actually small, ceramic-like pellets of uranium dioxide. Each one is about the size of a pencil eraser.

One of those tiny pellets has as much energy as:

💡 You might also like: Alien Earth T Ocellus: What We Actually Know About These Strange Planetary Structures

- About 150 gallons of oil.

- One ton of coal.

- 17,000 cubic feet of natural gas.

Thousands of these pellets are stacked into long zirconium tubes called fuel pins. These pins are then bundled into "assemblies." A large reactor might have 200 of these assemblies, each containing hundreds of pins. When you look inside a nuclear reactor during a refueling outage, you see these assemblies being moved underwater by massive overhead cranes. The water acts as both a coolant and a radiation shield, allowing workers to stand right above the pool without getting a dose.

Refueling: The big logistics dance

Every 18 to 24 months, the plant has to shut down for refueling. You can’t just "top off" the tank. They have to peel back the massive steel head of the reactor vessel.

During this time, about a third of the fuel is replaced. The "spent" fuel is moved to a nearby pool. This is another area where people get nervous. Spent fuel is definitely "hot" in both the thermal and radioactive sense. But it’s kept in deep pools of circulating water for several years until it cools down enough to be moved into "dry casks"—massive steel and concrete canisters that sit out on a concrete pad.

Experts like Dr. Kathryn Huff, former Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy, often point out that all the spent nuclear fuel ever produced in the U.S. could fit on a single football field, stacked about 50 feet high. Compared to the millions of tons of CO2 and fly ash produced by coal plants, the "waste" footprint is actually tiny.

What it feels like on the floor

Working inside a plant is weirdly clinical. It’s loud in the turbine hall, but the reactor area is usually quite hushed. There’s a constant hum of pumps. Everything is painted in "nuclear gray" or white.

You’ll wear a dosimeter, a little device that tracks your radiation exposure. Honestly, you probably get more radiation flying from New York to LA than a technician gets during a standard shift at a nuclear plant. The safety culture is intense. I’m talking "triple-checking the ladder before you climb it" intense.

Common misconceptions about the interior

We need to clear some things up. First, the cooling towers. You know, the big curvy ones? Those aren't always there. Many reactors use lake water or ocean water and don't even have those towers. If they do, they are literally just big chimneys for heat.

Second, the "leak" myth. Modern reactors use a "defense-in-depth" strategy. There are multiple physical barriers between the uranium and you:

- The ceramic fuel pellet itself (it holds onto the fission products).

- The zirconium cladding of the fuel pin.

- The 8-inch thick steel reactor vessel.

- The several-foot-thick concrete containment building.

If one fails, the next one catches it.

The future of the "Inside"

We are moving away from the giant, multi-billion dollar "light water" reactors of the 70s. The next generation—Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)—are being built now. Companies like NuScale and TerraPower (backed by Bill Gates) are designing reactors that are smaller and often use different coolants, like molten salt or liquid sodium.

In a molten salt reactor, the "inside" looks totally different. The fuel is actually dissolved into the liquid salt. If the system gets too hot, a "freeze plug" at the bottom melts, and the fuel drains by gravity into a cooling tank where the reaction naturally stops. It’s passive safety. No pumps or electricity required to prevent a meltdown. It’s basically physics doing the heavy lifting.

Real-world insights for the curious

If you’re interested in what’s happening inside a nuclear reactor or considering a career in the field, there are a few things you should actually do rather than just reading Wikipedia.

- Look up the NRC's public records. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the US is incredibly transparent. You can find "Event Reports" for every single power plant. It’s boring, technical, and shows you exactly how often small things get fixed.

- Virtual Tours. Some plants, like Byron Station in Illinois, have offered virtual or physical tours in the past. It’s the only way to get a sense of the scale of the steam pipes.

- Check out the "World Nuclear Association" database. If you want the hard data on how much fuel is being used globally, this is the gold standard source.

Actionable next steps

If you want to understand this technology better or support its deployment:

- Understand your local grid. Use a tool like "Electricity Maps" to see where your power actually comes from. If you live in Illinois, South Carolina, or New Jersey, a huge chunk of your clean energy is coming from a reactor core right now.

- Research SMRs. Look into the "Voyager" project by NuScale. It’s the first SMR to receive design approval from the NRC.

- Advocate for life extensions. Many existing plants are being decommissioned because of market pressure from natural gas, not safety. Extending the life of a plant like Diablo Canyon in California is one of the fastest ways to keep carbon emissions down.

- Follow the science, not the hype. Nuclear energy is a polarizing topic. Stick to sources like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for global safety standards and the Department of Energy (DOE) for technical breakthroughs.

The inside of a reactor is a place of incredible order and power. It isn't a sci-fi nightmare; it's just a very hot, very high-pressure steam engine fueled by the fundamental forces of the universe. Understanding how it works is the first step in stripping away the fear and seeing it for what it is: a tool.