You’re walking down a sidewalk and see a guy soaking wet, holding a mangled umbrella, looking absolutely miserable. It hasn't rained in your neighborhood all day. Yet, instantly, you know it’s pouring three blocks over. You didn't see the rain. Nobody told you about the storm. You just did it. You reached a conclusion based on evidence and reasoning rather than explicit statements. That, in its simplest form, is the definition of an inference.

It’s the "reading between the lines" of human existence. Honestly, without this mental shortcut, our brains would stall out every five seconds. We’d be like literal-minded robots, unable to understand sarcasm, literature, or why our partner is giving us "that look" over the dinner table.

What an Inference Actually Is (and Isn't)

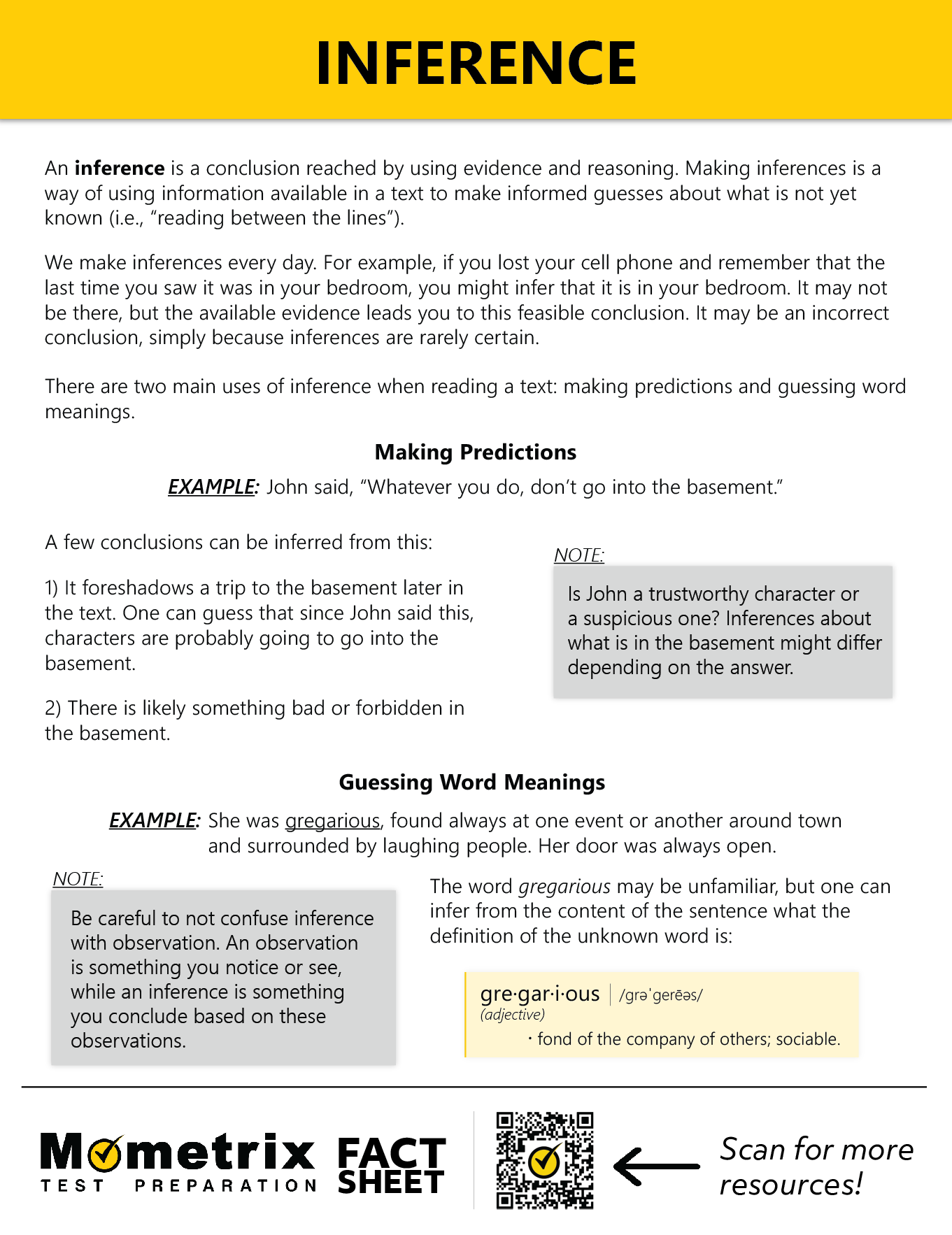

Most people confuse an inference with a guess. They aren't the same. A guess is a shot in the dark, like picking a lottery number or wondering if there's cheese in the fridge without checking. An inference is a calculated leap. It requires two specific ingredients: the "clues" (evidence) and your "schema" (prior knowledge).

When you see smoke, you infer fire. Why? Because your life experience has taught you that smoke is a byproduct of combustion. You aren't guessing there’s a fire; you’re using logical deduction. However, it's not an observation. An observation is seeing the flames. An inference is knowing they’re there because the chimney is puffing out gray clouds.

In the world of logic and philosophy, we often look at this through the lens of Charles Sanders Peirce, who talked about "abductive reasoning." It’s about finding the most likely explanation for a set of facts. If the grass is wet in the morning, did a giant water balloon pop? Maybe. Did a localized portal to the ocean open? Unlikely. Did the sprinklers run? Probably. That "probably" is where the inference lives.

The Mechanics of the Mental Leap

It happens fast. Too fast to notice.

🔗 Read more: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Think about reading a novel. The author writes: "Sarah slammed the door and threw her keys onto the marble counter, not even bothering to take off her muddy shoes." The author never says Sarah is angry. They don't have to. You’ve inferred her emotional state from her actions. You’ve combined the evidence (door slamming, muddy shoes on a clean floor) with your knowledge (angry people are often reckless or aggressive).

If we needed every single detail spelled out, a 300-page book would be 3,000 pages long. Language relies on the definition of an inference to function efficiently. We leave gaps because we trust the listener to bridge them.

Where We Get It Wrong: The "Assumption" Trap

Here is where it gets messy. Every inference is a risk. You might be wrong.

Maybe Sarah wasn't angry. Maybe she was in a desperate rush to catch a phone call and her muddy shoes were an accident. When an inference is based on insufficient evidence or personal bias, it curdles into an assumption. Assumptions are the junk food of the mind—easy to consume but usually bad for you.

Psychologists like Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, point out that our brains love "heuristics." These are mental shortcuts. While they help us survive, they also lead to "jumping to conclusions." If you see a person in a lab coat, you infer they are a doctor. But they could be a butcher, a chemist, or someone heading to a Halloween party. The strength of your inference depends entirely on the quality of your evidence.

💡 You might also like: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Why Context Is King

Context is the guardrail for our thoughts. Without it, the definition of an inference falls apart. Take the sentence: "The bank was closed."

If you're walking downtown with a check in your hand, you infer the financial institution has ended its business hours. If you're rowing a boat down a river and see a fence across a muddy slope, you infer that the riverbank is inaccessible. The words are identical. The evidence changes based on the environment. This is why AI often struggles with deep inference; it lacks the "lived experience" to know which "bank" we're talking about unless we provide mountains of data.

Inferences in Different Fields

It's not just for English teachers or detectives.

- In Science: Scientists use the definition of an inference to form hypotheses. When astronomers detect a slight wobble in a distant star, they don't see a planet. They infer a planet is there because its gravity is tugging on the star.

- In Medicine: A doctor looks at a rash, hears about a fever, and notes a high white blood cell count. They infer an infection. They haven't seen the bacteria under a microscope yet, but the "clues" point to a specific culprit.

- In Law: "Circumstantial evidence" is basically just a fancy legal term for a series of inferences. If a defendant was seen running from a house with a bag of jewelry, the jury is asked to infer they committed the robbery.

Statistical Inference: The Math Version

There is a more formal side to this, too. In statistics, we talk about "inferential statistics." This is when you take a small slice of data (a sample) and use it to make a claim about a huge group (the population).

If you poll 1,000 people and 60% say they like chocolate ice cream, you infer that most people in the country feel the same way. You haven't asked everyone. You’re making a mathematical leap based on probability. It’s powerful, but as any pollster will tell you, it's also prone to error if your sample is skewed.

📖 Related: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

How to Get Better at Making Inferences

We do this thousands of times a day, but most of us are sloppy. We let our moods or prejudices tint the lens. Improving your "inference game" makes you a better communicator, a sharper worker, and honestly, a less frustrated human being.

First, stop and look for the "anchor." What is the one piece of undeniable fact you are looking at? If your boss hasn't replied to your email in four hours, the fact is that there is no reply. The inference that they are mad at you is a reach. It's much more likely they are in meetings or haven't seen it.

Second, check your schema. Your prior knowledge might be outdated. If you infer that a "professional" person must wear a suit, you’re going to be very confused when you walk into a Silicon Valley headquarters. Your internal "rulebook" needs a regular update.

Third, look for alternative explanations. This is what scientists do. They try to "falsify" their own inferences. Before you decide that your friend is ignoring you because they're "over" the friendship, ask yourself: "What else could this mean?" Maybe their phone broke. Maybe they're overwhelmed.

The Actionable Path to Sharp Reasoning

To truly master the definition of an inference, you have to treat your brain like a detective. Don't just accept the first story your mind tells you.

- Differentiate the Data: In any situation, mentally separate what you see from what you think it means. "He is frowning" is a fact. "He is unhappy with me" is an inference. Keeping those two buckets separate prevents emotional spiraling.

- Verify via Inquiry: The easiest way to check an inference? Ask. "I noticed you were quiet in the meeting; are you worried about the project?" This turns a mental leap into a factual conversation.

- Read Diverse Perspectives: Inferences are built on your "knowledge base." If you only read one type of book or talk to one type of person, your inferences will be narrow and often wrong. Expanding your world expands your ability to read the world correctly.

- Practice Narrative Mapping: When watching a movie or reading a book, try to predict what happens next based on small clues. Notice when the director lingers on a specific object. That's a "clue" planted specifically for you to infer its future importance (Chekhov’s Gun).

We live in an age of information overload, but much of that information is incomplete. We are constantly forced to fill in the blanks. By understanding the definition of an inference, you stop being a passive consumer of your own thoughts and start being an active participant in how you perceive reality. It’s the difference between being led by your assumptions and being guided by your logic.

Next time you find yourself "knowing" something that hasn't been said, take a second to look at the footprints that led you there. Are they solid ground, or are you walking on air? The more you practice identifying your own mental leaps, the more accurate those leaps become. Stop guessing. Start inferring with intent.