You've heard the jokes. Anyone who has driven I-65 from Gary to Indianapolis probably thinks Indiana is just one giant, endless pool table made of corn and soybeans. It looks flat. It feels flat. But if you actually look at an Indiana topographical map, you’ll realize that the "Flyover Country" stereotype is a total lie.

Indiana is weird. It’s a state split in two by an ancient icy bulldozer.

The Great Divide: The Wisconsin Glaciation

If you want to understand why Indiana looks the way it does, you have to talk about the glaciers. About 20,000 years ago, the Wisconsin Glacial Episode basically flattened the northern two-thirds of the state. It acted like a massive piece of sandpaper, grinding down hills and filling in valleys with "till"—a messy mix of clay, sand, and gravel.

But the ice stopped.

It reached a certain point—roughly a line carving through the state—and just gave up. This is the "Glacial Boundary." South of this line, the land is rugged, carved by millions of years of water erosion rather than ice. When you look at an Indiana topographical map, you can see this line clearly. The north is a smooth gradient; the south is a chaotic mess of ridges and ravines.

Honestly, it’s like two different states.

The Highest and Lowest Points

Most people assume the highest point in Indiana would be some scenic overlook in the southern hills. Nope. It’s actually in a farmer's field in Wayne County. Hoosier Hill sits at 1,257 feet above sea level. It’s not a mountain. It’s barely a rise. You could drive past it and never know you’d reached the "peak" of the state.

On the flip side, the lowest point is down in Posey County, where the Wabash River meets the Ohio River. That’s about 320 feet. That roughly 900-foot difference doesn't sound like much compared to Colorado, but it’s how that elevation is distributed that matters.

The Knobstone Escarpment: Indiana’s "Mountains"

If you’re looking for drama, you head to the Knobstone Escarpment. This is the most prominent topographic feature in the state. It’s a series of steep siltstone hills that rise nearly 1,000 feet above the surrounding plains. To a hiker on the Knobstone Trail, it feels like the Appalachians.

The terrain here is brutal.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) manages this area, and they’ll tell you that the vertical gain on some of these trails rivals what you’ll find in much more "famous" mountain states. The hills—or "knobs"—are the result of the Borden Group of rocks resisting erosion better than the softer rocks around them.

The Karst Plain and the Holes in the Ground

Then there’s the limestone.

South-central Indiana is famous for its Karst topography. This isn't just about what's on the surface; it's about what's missing. Because limestone is slightly soluble in rainwater, the ground is literally dissolving. This creates sinkholes, disappearing streams, and massive cave systems like Bluespring Caverns and Marengo Cave.

- Sinkholes: In places like Orange and Lawrence counties, the topographical map looks like it has chickenpox. Thousands of little depressions dot the landscape.

- Disappearing Streams: You’ll see a creek on a map that just... stops. It goes underground, travels through a cave, and pops up miles away as a spring.

- Caves: Indiana has over 4,000 documented caves.

The Dunes: A Topographical Outlier

Up north, near Lake Michigan, the rules change again. The Indiana Dunes are a topographical anomaly. These aren't solid rock hills; they are shifting piles of sand, some rising 200 feet above the lake level. Mount Baldy is the most famous, known as a "living dune" because it moves several feet every year, swallowing trees and parking lots in its path.

The topography here was shaped by wind and the receding Great Lakes. It's a tiny sliver of the state that looks more like a coastal desert than the Midwest.

Why This Data Actually Matters

Why do we care about a bunch of squiggly lines on a map?

📖 Related: Ireland Paying to Move to Island: The Truth About the $92,000 Grant

- Agriculture: The flat northern till plains are some of the most productive farmland on Earth. The topography allows for massive, efficient industrial farming.

- Infrastructure: Building a highway in Hamilton County is cheap. Building one in Floyd County involves blasting through millions of tons of rock. This is why southern Indiana roads are famously curvy and expensive to maintain.

- Flash Flooding: In the hilly south, water moves fast. Topographical maps are the primary tool for the Indiana Silver Jackets (a multi-agency flood task force) to predict where the next "big one" will hit.

How to Read Indiana's Terrain Like an Expert

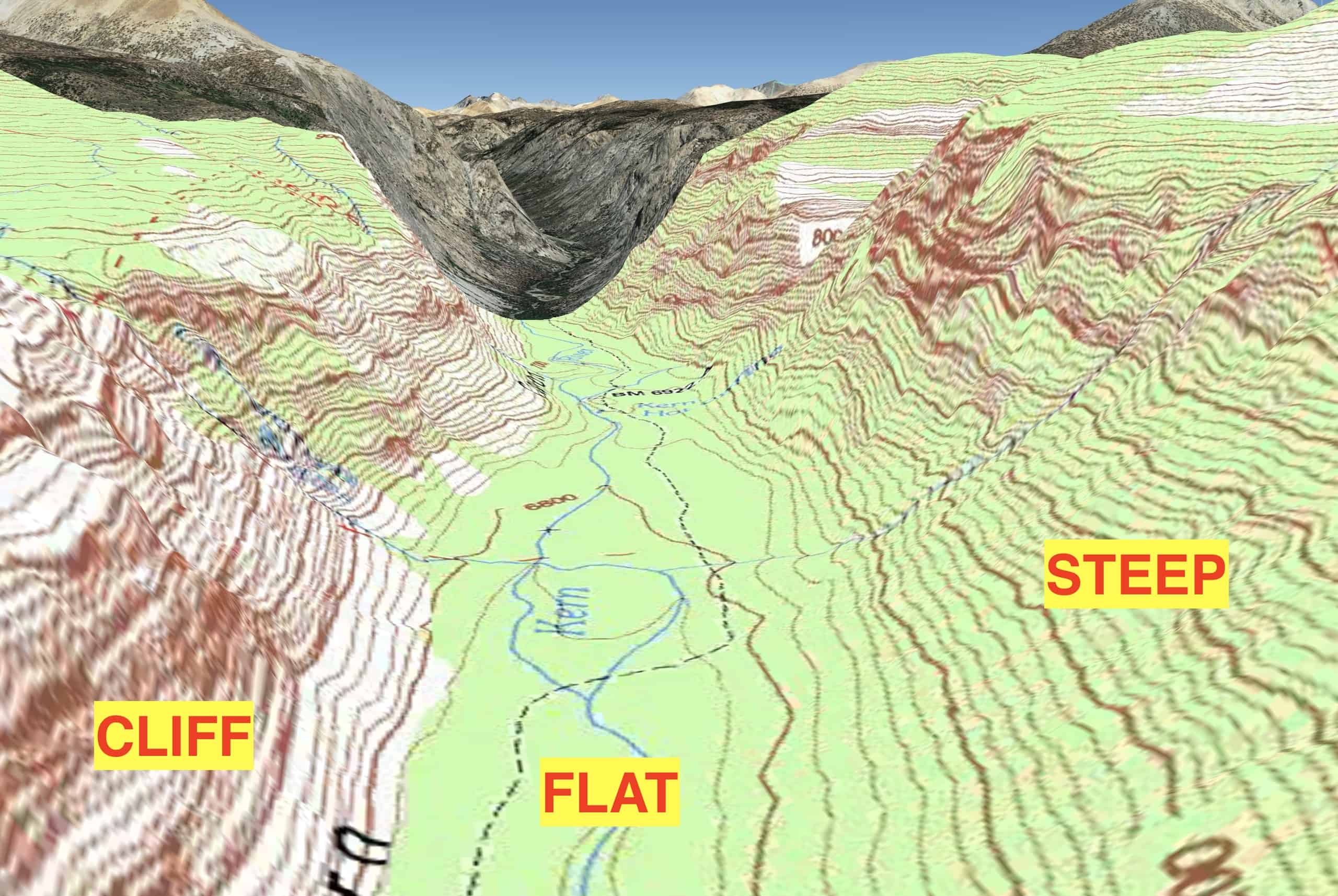

If you’re looking at a USGS (U.S. Geological Survey) map of the state, look for the "contour interval." In the north, those lines might be miles apart. In the south, specifically near the Ohio River, they’ll be stacked right on top of each other.

That "stacking" means steepness.

A great example is the Brown County State Park area. It’s often called the "Little Smokies." The elevation changes there aren't just for show; they create unique microclimates that support hemlock trees and rare plants that you won't find anywhere else in the state.

Myths vs. Reality

People think Indiana is a boring rectangle.

Geologically, it's a battleground. You have the Illinois Basin to the west and the Cincinnati Arch to the east. These deep structural features dictate where coal, oil, and limestone are found. The topography is just the skin on top of a very complex skeletal structure.

Even the "flat" parts aren't truly flat. The Kankakee Outwash Plain in the northwest was once one of the largest wetlands in North America before it was drained for farming. On a map, it looks like a dead level surface, but its history is written in the subtle sandy ridges that used to be prehistoric lake shores.

Practical Steps for Explorers

If you actually want to use an Indiana topographical map for something other than a school project, start with the Indiana Map website (indianamap.org). It’s a massive GIS (Geographic Information System) database run by the Indiana Geological and Water Survey.

You can overlay elevation data with soil types, bedrock geology, and even historical flood zones.

For hikers, download the Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) layers. Lidar uses lasers to map the ground through the trees. In the summer, Indiana's heavy canopy hides the terrain. Lidar strips the leaves away and shows you the "naked" earth. It’s how archaeologists find old foundations and how hikers find hidden waterfalls in the Hoosier National Forest.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

- For Hikers: Head to the Deam Wilderness in the Hoosier National Forest. Use a topo map to find the "saddles" between ridges—that’s where you’ll find the best campsites and the least wind.

- For Cyclists: If you want a challenge, the Hilly Hundred in Bloomington is the gold standard. It uses the state's natural topography to punish your legs over two days of riding.

- For Land Buyers: Always check the Lidar data before buying property in southern Indiana. A "flat" spot on a standard map might actually be a sinkhole filled with brush.

- For Photographers: The best topographical drama happens at sunrise in Brown County or Clifty Falls. The deep valleys trap morning mist, creating the "sea of clouds" effect usually reserved for the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Indiana isn't just a hallway between Chicago and Louisville. It’s a landscape of glacial scars, crumbling limestone, and hidden peaks. You just have to know where the ice stopped.

To get the most out of your exploration, start by downloading the 7.5-minute quadrangle maps from the USGS for the area surrounding Brown County State Park or the Hoosier National Forest. Compare the contour lines in these regions to a map of Tipton County. The visual difference alone will change how you perceive the geography of the Midwest forever. Use the Indiana Geological Survey’s interactive "Map Viewer" to toggle between "Shaded Relief" and "Bedrock Geology" to see exactly how the stone beneath your feet dictates the hills above them.