You’re probably lying on that bench at a 45-degree angle because you want those "shelf" pecs. We’ve all seen the guys in the gym chasing that specific upper-chest pop. But honestly, most people are just tossing weight around without actually hitting the right spots. If you want to master the incline dumbbell press muscles worked, you have to look past just the chest. It’s a complex symphony of fiber recruitment, and if your setup is off by even a few degrees, you're basically just doing a glorified shoulder press.

The incline press is tricky. It’s not just a flat press tilted up.

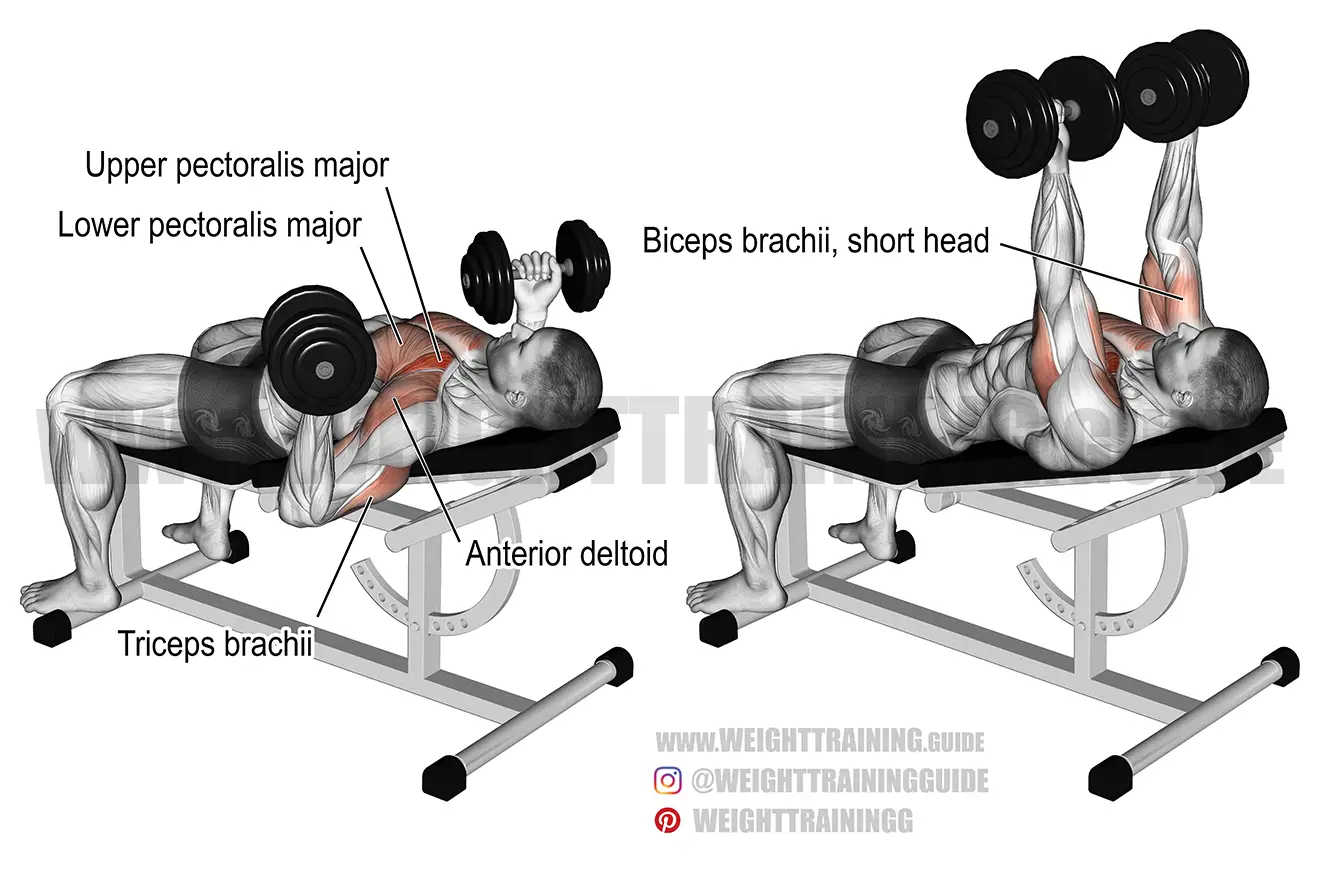

When you change the angle of the bench, you change the mechanical advantage of the muscle groups involved. The primary mover is the clavicular head of the pectoralis major. That’s the upper portion of your chest that attaches to your collarbone. In a standard flat press, the sternal head (the middle/lower part) does the heavy lifting. But the moment you incline that bench, the workload shifts north.

The Breakdown of Incline Dumbbell Press Muscles Worked

So, what’s actually firing when you press those bells?

The pectoralis major is the star, specifically that upper clavicular head we mentioned. Research, including EMG studies popularized by experts like Bret Contreras, consistently shows that an incline of 30 to 45 degrees significantly increases the activation of the upper chest compared to a flat bench. But it doesn't stop there.

Your anterior deltoids (the front of your shoulders) are heavily recruited here. In fact, if the incline is too steep—say, 60 degrees or more—the movement becomes almost entirely a shoulder exercise. This is a common mistake. You see people sitting almost upright, wondering why their chest isn't sore the next day. It’s because their delts took over the whole show.

Then you’ve got the triceps brachii. They act as the secondary movers, extending the elbow at the top of the movement. Without them, you aren't lockout out. But there’s a sneaky player involved too: the serratus anterior. These are the "boxer's muscles" that look like fingers on the side of your ribs. They help protract the scapula, keeping your shoulders stable as you push.

Why Dumbbells Change Everything

Why not just use a barbell?

Dumbbells allow for a greater range of motion. You can bring the weights lower and deeper than a bar, which would hit your chest and stop. This extra stretch at the bottom puts the pectoralis major under a massive amount of tension in a lengthened state. We know from modern hypertrophy research that training a muscle in its lengthened position is one of the most potent triggers for growth.

Also, dumbbells require a massive amount of stabilization. Your rotator cuff muscles—the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis—are working overtime to make sure those weights don't wobble and crush your face. This is why you can’t lift as much weight with dumbbells as you can with a barbell. Your brain is busy trying to keep you from dying.

The Science of the Angle

There’s a lot of debate about the "perfect" angle. Some bodybuilders swear by a low incline, maybe 15 or 30 degrees. They argue it keeps the tension on the chest while minimizing shoulder involvement.

✨ Don't miss: Baan: The Boundary of Adulthood and Why Our Brains Struggle With It

A 2010 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research looked at different bench angles and found that the 45-degree mark was a "sweet spot" for many, but as the angle increased, so did the activity in the front delts. If you go too high, you’re basically doing an Overhead Press. If you go too low, you're just doing a flat press with a weird vibe.

Honestly? Most commercial gym benches have notches that are too far apart. You might find that the second notch is perfect, but the third one turns your chest workout into a shoulder day. It pays to be mindful.

Synergy and Stabilizers

We talk a lot about the big muscles, but the coracobrachialis is a tiny muscle in the upper arm that helps with adduction and flexion at the shoulder. It's working. Your biceps brachii (specifically the short head) even plays a stabilizing role in the bottom of the movement to keep the shoulder joint "packed."

And don't forget the core.

If you aren't bracing your abs, you'll end up arching your back so much that you turn the incline press back into a flat press. You’ve seen this: the guy who arches his lower back so high you could drive a truck under it. He’s subconsciously trying to change the angle to use his stronger lower pecs. It’s cheating, basically. Keep your back relatively flush or with a natural arch, but keep those glutes on the bench.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Gains

- Flaring the Elbows: If your elbows are out at a 90-degree angle to your body, you are begging for an impingement. It puts a nasty amount of stress on the subacromial space. Tuck them in slightly, maybe at a 45 to 60-degree angle from your torso.

- The "Bouncing" Rep: People drop the dumbbells fast and bounce them off the stretch reflex. You’re losing the most valuable part of the lift. Control the eccentric. Feel the stretch.

- Partial Range of Motion: If you're only going halfway down, you're only getting half the muscle recruitment. Unless you have a specific injury, get those dumbbells deep.

- Ignoring the Feet: Your power starts at the floor. Drive your heels into the ground. This "leg drive" creates a stable platform for your upper body to push from.

How to Program for Maximum Upper Chest

If you’re looking to prioritize the incline dumbbell press muscles worked, you shouldn't just tack it onto the end of a long workout. Put it first. Your central nervous system is freshest at the start of the session.

Try a rep range of 6 to 10 for strength-based hypertrophy, or 12 to 15 if you’re focusing on the metabolic stress and the "pump."

Specific variations can also help. Some people like a neutral grip (palms facing each other). This can be easier on the shoulders and sometimes allows for a deeper stretch. Others prefer the standard pronated grip for maximum pec tension. There is no one-size-fits-all here; your anatomy, specifically the length of your humerus and the width of your ribcage, will dictate what feels best.

The Mind-Muscle Connection

It sounds like "bro-science," but it’s real. Thinking about the upper chest fibers shortening as you press helps. Instead of thinking "push the weight up," think about "squeezing your biceps together." This internal cue often leads to better pec activation.

Wait, why biceps? Because the primary function of the pec major is horizontal adduction—bringing your arm across your body. By trying to bring your inner arms toward your midline, you force the chest to do the work rather than just the triceps.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Chest Day

To truly master the incline dumbbell press and see real growth in your upper chest, you need a plan that goes beyond just lifting heavy things.

- Adjust Your Bench: Start at 30 degrees. If you feel it mostly in your shoulders, drop it a notch. If you don't feel a stretch in the upper pec, try 45.

- Tempo Control: Spend 3 full seconds on the way down. Hold the stretch at the bottom for 1 second. Explode up.

- Record Yourself: Set up your phone and film a set from the side. Are your forearms vertical? They should be. If they're tilting in or out, you're losing force and risking your joints.

- Progressive Overload: Don't just stay with the 50s forever. Even adding 2.5-pound "fractional" plates or simply doing one more rep than last week is progress.

- Pairing: Try supersetting incline presses with a stretch-focused movement like incline dumbbell flies or a cable crossover to fully fatigue the fibers.

The upper chest is notoriously stubborn. It’s a smaller muscle area compared to the mid-sternal region, and it’s often overshadowed by the shoulders. But with the right incline, a controlled range of motion, and a focus on the specific incline dumbbell press muscles worked, you can build that "armor-plated" look. Stop ego lifting and start feeling the muscle. Your shoulders (and your progress) will thank you.