You’re staring at a service manual for your mountain bike or maybe the valve cover on your car, and there it is: a torque spec that makes no sense. It says inch pounds to pounds, or maybe it just says "in-lbs," and you've only got a giant torque wrench calibrated in foot-pounds sitting in your greasy toolbox.

Mistakes here are expensive.

Snap a bolt inside an aluminum engine block because you did the math wrong in your head, and you aren’t just looking at a ruined afternoon. You’re looking at a multi-thousand-dollar trip to the machine shop. It happens because people treat these units like they’re interchangeable or, worse, they try to "feel" 80 inch-pounds with a 2-foot breaker bar. You can't. Physics won't let you.

The fundamental math of torque

Let’s get the "technical" part out of the way before we talk about why people actually fail at this. Torque is just force times distance. If you have a one-foot-long wrench and you hang a one-pound weight off the end of it, you’ve got one foot-pound of torque. Simple.

But what if your wrench is only an inch long? To get that same twisting power, you’d need a lot more weight. Specifically, 12 times more. This is why the conversion from inch pounds to pounds (specifically foot-pounds) is always centered around that magic number: 12.

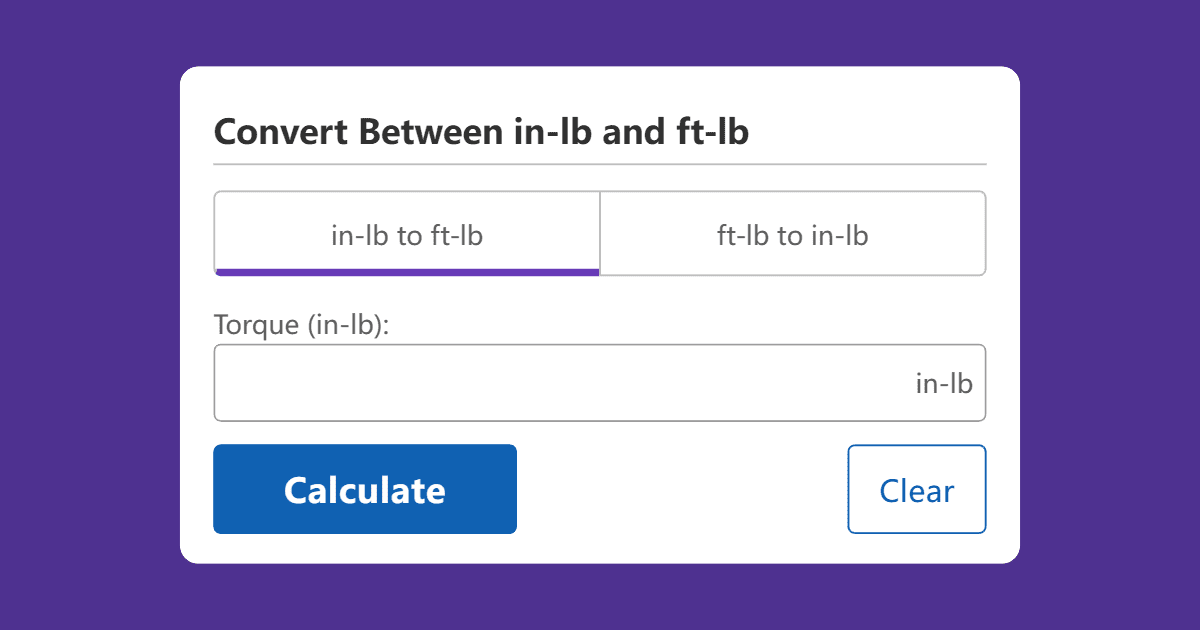

To convert inch-pounds to foot-pounds, you divide by 12.

$T_{ft-lb} = \frac{T_{in-lb}}{12}$

To go the other way, you multiply. If a bolt requires 15 foot-pounds and your wrench only reads in inch-pounds, you're looking for 180. 15 times 12. Most people can do that math. The problem isn't the math; it's the tools and the physics of leverage.

Why "Pounds" isn't actually a unit of torque

We need to be honest about terminology. When people search for inch pounds to pounds, they are usually looking for foot-pounds. "Pounds" on its own is a measure of weight or force. Torque is a "moment"—it's a twisting force.

Imagine you’re trying to open a stubborn pickle jar. The force you’re gripping with is measured in pounds. The actual twisting motion you apply to the lid is torque. If you tried to describe how hard you're twisting just by saying "10 pounds," a scientist would look at you like you have two heads. They’d ask, "10 pounds at what distance from the center?"

Distance is the lever arm. This is why a longer wrench makes it easier to loosen a lug nut. You aren't getting stronger; you're just increasing the "d" in the $Torque = Force \times Distance$ equation.

🔗 Read more: The Singularity Is Near: Why Ray Kurzweil’s Predictions Still Mess With Our Heads

The Danger of the "Bottom Third"

Here is a secret that tool manufacturers don't like to put in big red letters on the box: most torque wrenches are notoriously inaccurate in the bottom 20% to 30% of their range.

If you have a heavy-duty torque wrench that goes from 20 to 250 foot-pounds, and you try to use it for a spec that calls for 20 foot-pounds, you are playing Russian roulette with your hardware. At that low end, the internal spring tension is barely engaged. The "click" might be so faint you miss it, or the calibration might be off by 10% or more.

This is exactly why inch-pound wrenches exist. Small fasteners—think electronics, bicycles, plastic intake manifolds—need precision. If you're converting inch pounds to pounds because you want to use your big 1/2-inch drive wrench on a tiny M6 bolt, stop. Just stop. You will strip the threads.

Real World Scenarios: When it Matters

Let's look at a common scenario in a garage. You're working on a transmission pan. The spec calls for 120 inch-pounds. You think, "Okay, 120 divided by 12 is 10. I'll just set my big wrench to 10 foot-pounds."

Except your big wrench starts at 10.

At that setting, the wrench is at its absolute limit of unreliability. Furthermore, the sheer weight of a 1/2-inch drive torque wrench makes it hard to feel the fastener "giving" before it breaks. When working with small numbers, use the tool designed for small numbers. 120 inch-pounds feels like a lot on a small 1/4-inch drive wrench, but it feels like nothing on a big one. That lack of tactile feedback is how bolts get snapped.

Aerospace and Precision Engineering

In the world of aviation, the conversion of inch pounds to pounds is a matter of life and death. Mechanics like those certified by the FAA follow strict guidelines (like those found in AC 43.13-1B) regarding torque. In these environments, you don't "guess" a conversion.

Aviation fasteners are often made of specific alloys that stretch slightly when torqued—this is called "preload." If you're off by even a few inch-pounds, the vibration of a jet engine can cause that fastener to back out or, worse, suffer from fatigue failure.

The "Dry vs. Wet" Debate

Here is something that almost nobody talks about when they’re looking up torque conversions: friction.

💡 You might also like: Apple Lightning Cable to USB C: Why It Is Still Kicking and Which One You Actually Need

Most torque specs are calculated for "dry" threads. This means no oil, no grease, and no anti-seize. If you put a drop of oil on a bolt and then torque it to the spec you found online, you are actually over-tightening it.

Why? Because the lubricant reduces friction, allowing the bolt to turn further for the same amount of torque. This can increase the actual tension on the bolt by 20% to 40%. If you're converting inch pounds to pounds for a head bolt or a critical suspension component, you have to know if that spec is "wet" or "dry."

- Dry Threads: Standard friction.

- Lubricated Threads: Requires a reduction in torque (often 20-30%).

- Loctite/Threadlocker: Acts as a lubricant while wet, then a locker when dry. Treat as "wet" for the initial torque.

Common Fastener Specs

You’ll see different units depending on where your equipment was made.

- Metric (Newton-Meters): Most of the world uses Nm. 1 foot-pound is roughly 1.35 Nm.

- SAE (Foot-Pounds): Standard for American automotive work.

- SAE (Inch-Pounds): Standard for small-scale precision work.

If you find yourself frequently converting inch pounds to pounds, it’s worth printing out a small chart and taping it to the lid of your toolbox. Relying on your phone’s calculator when your hands are covered in grease is a recipe for a dropped (and cracked) screen.

Practical Tips for Accurate Torquing

First, always store your torque wrench at its lowest setting. If you leave it cranked up to 100 foot-pounds for three months, the internal spring will lose its "memory" and your calibration will drift.

Second, never use a torque wrench to loosen a bolt. That’s what breaker bars are for. Using a torque wrench as a crowbar is the fastest way to turn a $200 precision instrument into a fancy hammer.

Third, the "click." It's not a suggestion. When the wrench clicks, you stop. Don't give it that extra "tiny nudge" just to be sure. That extra nudge can easily add 5-10 inch-pounds of force, which, on a delicate aluminum thread, is the difference between a secure fit and a stripped hole.

Expert Insight: The Feel of the Metal

Kinda sounds weird, but you eventually learn to "feel" the yield point. When you're tightening a bolt, the resistance should be linear. It gets harder and harder to turn at a steady rate. If you're pulling and suddenly the resistance stays the same or—heaven forbid—gets slightly easier, you've reached the yield point. The bolt is stretching.

If you're at that point and your torque wrench hasn't clicked yet, something is wrong. Either your wrench is out of calibration or you've messed up the inch pounds to pounds conversion. Stop immediately. Back the bolt out and check the threads.

📖 Related: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

Does the Size of the Socket Matter?

Strictly speaking, no. The torque is measured at the drive square of the wrench. However, using long extensions can introduce "wind-up." This is especially true with thin extensions where the metal itself twists slightly before the bolt turns. For the most accurate conversion and application, use the shortest extension possible.

Final Steps for Success

To get this right, you need a process. Don't just wing it.

Start by cleaning your threads. Use a wire brush or a thread chaser if there's old gunk in there. Next, verify your source. Is that 120 in-lb spec from a forum post or a factory service manual? Forum posts are notoriously wrong.

Once you have the number, do the math twice. 120 / 12 = 10. Simple, but easy to mess up if you're tired.

Check your tool. If you’re using an inch-pound wrench, ensure it’s actually in inch-pounds and not Newton-meters, as some digital ones toggle between both.

Finally, pull with a smooth, steady motion. Jerking the wrench will cause the internal mechanism to trip prematurely or late. A steady two-second pull until the "click" is the gold standard.

By understanding the relationship between force and distance, you move beyond just "tightening bolts" and start practicing actual mechanics. It’s the difference between a job done and a job done right.

Check your torque wrench calibration every year if you use it frequently, or at least compare it against a new one if you suspect it’s drifting. Accurate torque isn't just about preventing things from falling off; it's about ensuring the engineering of the machine works exactly as the designers intended.