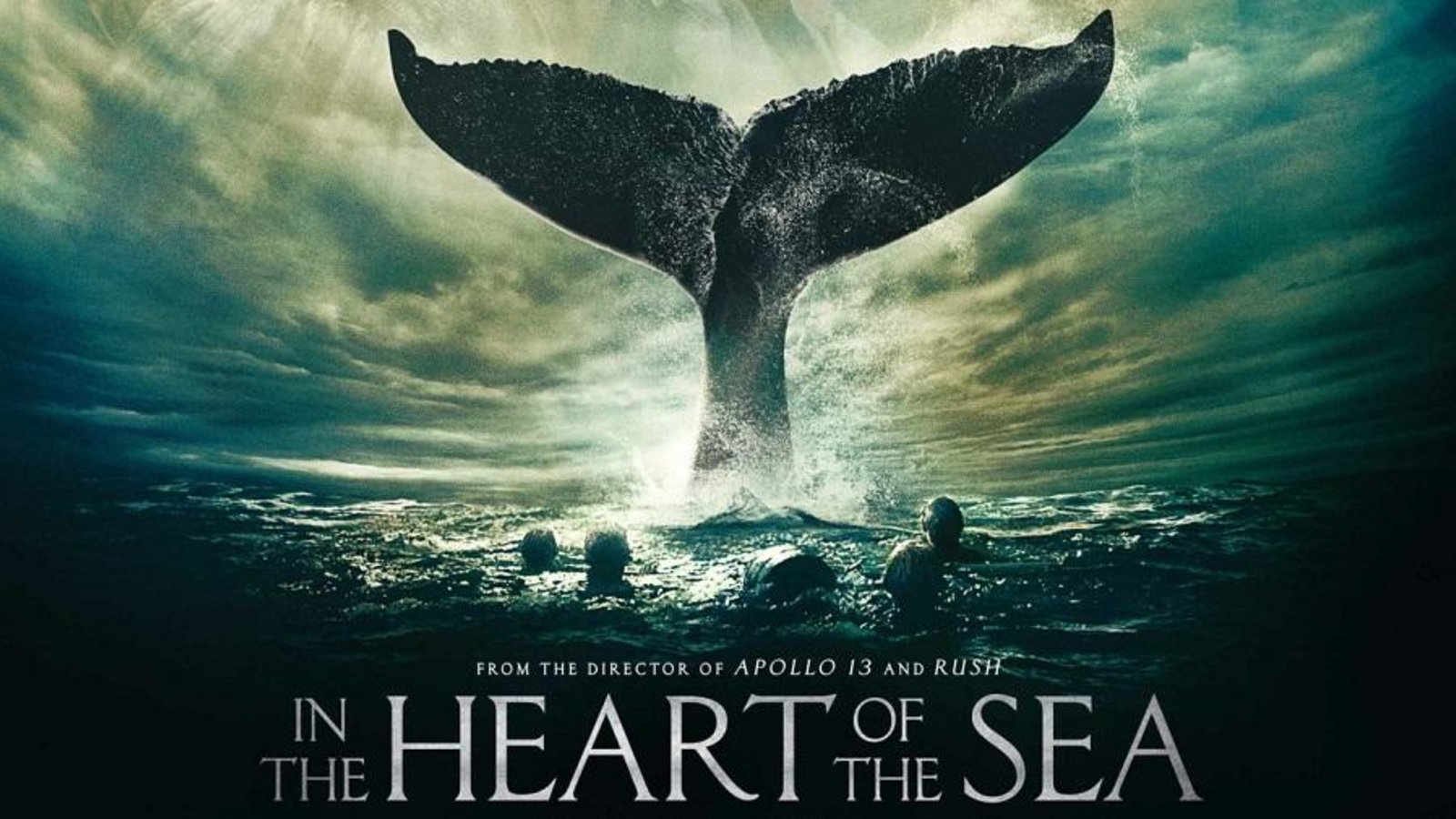

Ninety days. That is how long the crew of the Essex drifted in the open Pacific after a vengeful sperm whale smashed their ship to pieces. Most people know the name Moby-Dick, but Herman Melville didn’t just pull that story out of thin air. He based it on the 1820 sinking of a Nantucket vessel that turned into a literal nightmare. In the Heart of the Sea—both the award-winning book by Nathaniel Philbrick and the 2015 Ron Howard film—tries to capture that descent from professional whaling into absolute desperation.

It's a brutal story. Honestly, it’s one of those historical events that feels too cinematic to be real, yet the primary sources from survivors like Owen Chase and Thomas Nickerson prove every grisly detail.

Whaling in the 19th century wasn't some romantic adventure. It was an industrial operation. Nantucket was the oil capital of the world, and men went out for years at a time to hunt "liquid gold." But when the Essex left port in 1819, it was already a "hoodooed" ship. It got hit by a squall almost immediately. Maybe they should have turned back. They didn’t.

The Day the Whale Struck Back

When we talk about the sinking of the Essex, we're talking about a freak occurrence. Sperm whales are generally shy. They dive deep. They run away. But on November 20, 1820, an enormous bull—roughly 85 feet long—decided he’d had enough of the small harpoon boats buzzing around his pod.

First mate Owen Chase was on board the main ship repairing a boat when he saw it. This wasn't a passive collision. The whale rammed the ship, swam underneath it, and then turned around to deliver a final, crushing blow to the bow.

"I turned around and saw him about one hundred rods directly ahead of us," Chase wrote. The whale was moving at about twice its normal speed. The impact was so violent that men were thrown off their feet. The Essex began to settle. In less than twenty minutes, the ship was gone, and twenty men were left in three tiny whaleboats in the middle of the most remote part of the ocean.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Why In the Heart of the Sea Still Matters

You've got to wonder why we are still obsessed with this specific shipwreck two centuries later. It’s partly the "nature’s revenge" angle, but mostly it’s the psychological breakdown that followed. These weren't just sailors; they were Quakers from a tight-knit community.

Philbrick’s book, In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, won the National Book Award because it didn't just list dates. It looked at the biology of starvation. It looked at how the human brain starts to eat itself when the body runs out of fuel.

The Survival Math

The survivors made a fatal mistake early on. They were afraid of cannibals. They were near the Marquesas Islands, but rumors of "savages" scared them off. So, instead of sailing toward land they could actually reach, they tried to sail against the wind for 3,000 miles to reach South America.

It was a death sentence.

They spent months under a blistering sun. Their skin peeled. Their kidneys began to fail. When you read the accounts, you realize that the movie version with Chris Hemsworth, while visually stunning, had to sanitize the reality. You can't really show the full extent of what happens when a crew decides to draw lots to see who gets eaten next.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

- Captain George Pollard Jr. – He wanted to head to the islands. He was overruled by his officers.

- Owen Chase – The charismatic leader who perhaps prioritized his own survival over the collective good.

- Charles Ramsdell – The teenager who eventually had to pull the trigger on his best friend.

Separating the Movie from History

Ron Howard’s film version of In the Heart of the Sea does a lot right. The scale of the whale is terrifying. The "CGI" doesn't feel like CGI; it feels like a monster from a nightmare. But Hollywood loves a hero, and history is messier than that.

In the film, there's a heavy focus on the rivalry between the "green" Captain Pollard and the experienced First Mate Chase. While there was definitely tension, the actual journals suggest a more grinding, soul-crushing exhaustion rather than a high-stakes personality clash. The movie also frames the story through an interview between a young Herman Melville and an aged Thomas Nickerson (played by Brendan Gleeson). This is a great narrative device, but in reality, Melville got most of his information from reading Owen Chase's published account and briefly meeting Pollard years later.

Pollard is the real tragic figure here. After surviving the Essex, he got another ship. It sank too. He spent the rest of his life as a night watchman on Nantucket, a man literally haunted by the sea.

The Ecological Impact We Ignore

We usually focus on the horror, but there is a massive environmental subtext to this story. In the 1820s, people didn't think about "sustainability." They thought the ocean was infinite.

The Essex had to travel all the way to the "Offshore Ground" in the South Pacific because they had already hunted the Atlantic populations to near extinction. The whale that sank the Essex wasn't just a monster; it was an animal under siege. Modern marine biologists suggest the whale might have been reacting to the "acoustic" environment—the sound of the sailors hammering on the boats might have sounded like a challenge from another bull whale.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

What to Do If You're Fascinated by the Essex

If this story has its hooks in you, don't just stop at the movie. There is so much more to the actual history that gets left out of 120 minutes of screentime.

Read the Primary Sources

Start with Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex by Owen Chase. It's intense. Then, look for Thomas Nickerson's account, which wasn't discovered until 1960. It offers a much different perspective than Chase's "heroic" version.

Visit Nantucket

If you’re ever in Massachusetts, the Nantucket Whaling Museum is incredible. They have a massive sperm whale skeleton hanging from the ceiling and original artifacts from the era. You can actually stand in the space where these men lived. It makes the tragedy feel a lot more personal and a lot less like a legend.

Understand the Biology

Research "starvation physiology." It sounds macabre, but understanding what the crew of the Essex went through physically helps you empathize with the impossible choices they made. It wasn't malice; it was biology.

Watch the Documentaries

There are several great PBS specials on the Essex and the history of whaling. They provide the context of why these men were out there in the first place—essentially to keep the lights on in London and New York.

The story of In the Heart of the Sea is ultimately a humbling reminder. We think we’ve conquered nature, but we’re really just guests. When the Essex met that whale, the "civilized" world met a force it couldn't calculate or control. That’s why we’re still talking about it 200 years later. It’s the ultimate "man vs. nature" tale, and nature won.

To dive deeper into the maritime history, track down the 19th-century charts of the Pacific. Seeing the vast "white space" on the maps those men used helps you realize just how lost they actually were. It wasn't just a shipwreck; it was a disappearance into the void.