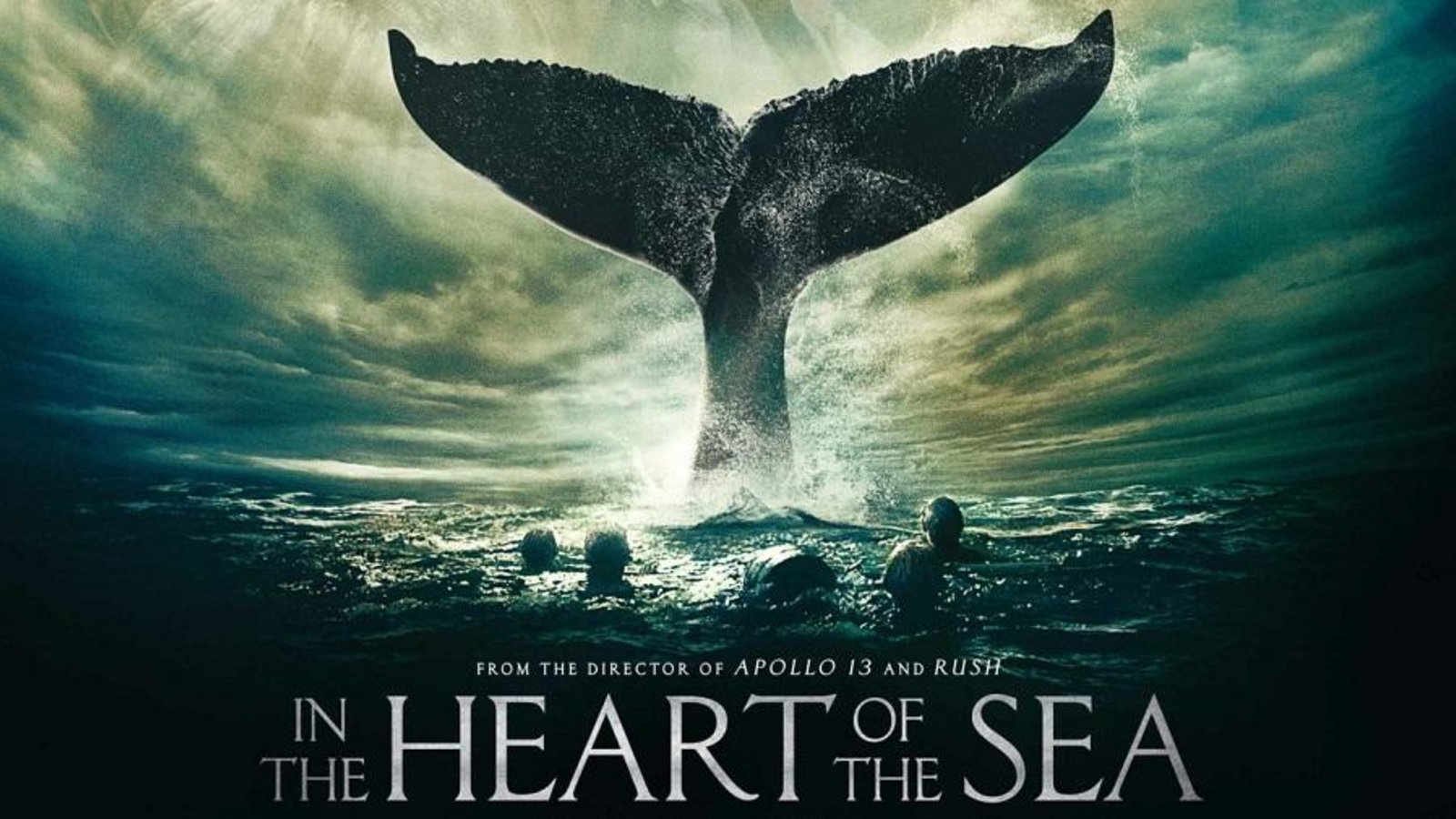

People usually think of Moby-Dick when they imagine a giant white whale smashing a ship to splinters. But Herman Melville didn’t just pull that out of thin air. He based his masterpiece on a real-life nightmare that happened in 1820. That nightmare is the backbone of the In the Heart of the Sea novel by Nathaniel Philbrick. If you’ve only seen the Ron Howard movie, you’re honestly missing about 70% of the actual grit. Philbrick didn't just write a history book; he wrote a forensic reconstruction of what happens to the human psyche when you're stuck in a leaky rowboat in the middle of the Pacific with nothing to eat but your friends.

It's a heavy read.

The book focuses on the whaleship Essex. It was an old, "lucky" ship out of Nantucket that got absolutely wrecked by an eighty-five-foot sperm whale. That's not a spoiler—it’s the premise. What makes Philbrick’s work stand out among maritime histories is how he weaves together the sociology of Nantucket, the biology of whales, and the terrifying physics of starvation.

The Nantucket You Didn't See in History Class

Nantucket in the early 19th century wasn't some quaint vacation spot. It was a high-stakes, industrial powerhouse fueled by oil. Only, the oil came from the heads of massive sea mammals. Philbrick spends a good chunk of the In the Heart of the Sea novel explaining the "Quaker Mafia" that ran the island. These were people who preached non-violence but built a global empire on the most violent industry imaginable.

The social hierarchy was suffocating. If you weren't a Coffin, a Starbuck, or a Macy, you were basically nobody. This matters because when the Essex went down, those social ranks didn't just disappear. They dictated who got the extra scrap of bread and who was first to suggest the "custom of the sea"—which is just a fancy maritime term for cannibalism. Philbrick makes it clear: the tragedy wasn't just the whale. It was the ego of Captain George Pollard and the misplaced ambition of First Mate Owen Chase. They didn't trust each other, and that lack of cohesion turned a disaster into a slow-motion massacre.

Why the Whale Actually Attacked

One of the biggest misconceptions people have after watching the film version of the In the Heart of the Sea novel is that the whale was some kind of vengeful monster with a grudge. Philbrick approaches this differently. He looks at it through the lens of animal behavior.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The Essex was being repaired. The crew was hammering on the hull. To a sperm whale, which navigates and communicates through complex acoustic clicks, that rhythmic hammering likely sounded like a challenge or a threat from another bull whale. It wasn't "evil." It was a biological response to an acoustic intruder.

- The whale was estimated at 85 feet long.

- It weighed roughly 80 tons.

- The ship was only 87 feet long.

Imagine a school bus being rammed by something the size of a Boeing 737. Twice. The first hit stunned the whale; the second hit sunk the ship. The speed at which the Essex went down is one of the most terrifying sequences Philbrick describes. One minute they’re hunting; the next, they’re standing on the deck of a sinking ship, 2,000 miles from the nearest coast, watching their livelihood disappear into the blue.

The Psychological Toll of the Open Ocean

The middle section of the book is where things get truly dark. Most survival stories focus on the "how-to," but Philbrick focuses on the "what-if." He uses modern medical knowledge to explain what dehydration and starvation do to the human brain. You stop being yourself. You start hallucinating. Your skin literally starts to fall off because of the salt spray.

There is a specific moment in the In the Heart of the Sea novel where the survivors have to make a choice. They could have sailed toward the Society Islands. They would have reached them in weeks. But they were terrified of rumors of cannibals.

The irony is almost too much to handle.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Because they were afraid of "savages" eating them, they chose to sail thousands of miles in the opposite direction, toward South America. By the time they were rescued, they had become exactly what they feared. They had survived by eating their own crewmates. Philbrick doesn't sensationalize this. He treats it with a somber, almost clinical respect that makes it ten times more haunting than any horror novel.

Owen Chase vs. George Pollard: A Study in Failed Leadership

Leadership isn't about being right; it's about being followed. In the In the Heart of the Sea novel, we see a fascinating, albeit tragic, power struggle. George Pollard was the Captain, but he was young and lacked the "alpha" presence of Owen Chase.

Chase was a charismatic, driving force. He was also arrogant. After the ship sank, Pollard wanted to go to the islands. Chase talked him out of it. If Pollard had stood his ground and exercised his authority, most of those men would have lived. Instead, he let his First Mate lead them into a graveyard of water.

Philbrick uses the primary source material—Chase's own narrative and the later-discovered account of Thomas Nickerson—to show how memory works. Chase wrote his book quickly to capitalize on the fame. He made himself the hero. Nickerson, who was just a cabin boy at the time, wrote his version much later, and it’s arguably more honest. It paints a picture of a crew that was fractured by race and class long before the food ran out.

The African American sailors died first. Every single one of them.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Philbrick points out that this wasn't just bad luck. They were given the smallest rations and held the least social capital on the boats. It’s a grim reminder that even in a survival situation, the prejudices of the land follow us out to sea.

The Legacy of the Essex

Why should anyone care about a 200-year-old shipwreck? Honestly, because it changed literature forever. Without the In the Heart of the Sea novel (or rather, the events it chronicles), there is no Moby-Dick.

Herman Melville actually met the son of Owen Chase. He read Chase's account while he was out at sea himself. He described the "extraordinary effect" it had on him. But where Melville went for symbolism and philosophy, Philbrick goes for the gut. He reminds us that the "White Whale" wasn't a metaphor for God or fate to the men on the Essex. It was a terrifying physical reality that ruined their lives.

Pollard eventually returned to sea, only to wreck his second ship on a coral reef. He was labeled a "Jonah"—a jinx. He ended his days as a night watchman in Nantucket, fasting every year on the anniversary of the sinking. There is a profound sadness in the way Philbrick tracks these men after their rescue. Survival wasn't a victory; it was a life sentence of guilt.

How to Approach the Book Today

If you’re planning to dive into the In the Heart of the Sea novel, you should prepare for a slow burn that turns into a fever dream. It’s not a beach read. It’s an autopsy of a disaster.

Key Insights for Readers

- Check the Maps: Philbrick includes detailed maps of the Pacific currents. Pay attention to them. It explains why they couldn't just "row" to safety. The ocean is a series of moving sidewalks, and they were going the wrong way on all of them.

- Research the Source Material: After finishing the book, look up Thomas Nickerson’s sketches. Seeing the drawings of a man who was actually there as a teenager adds a layer of reality that text can't quite capture.

- Understand the Quaker Context: The religious background of Nantucket is vital. It explains why the survivors felt such immense shame. To them, this wasn't just a tragedy; it was a divine judgment.

The In the Heart of the Sea novel remains one of the most important pieces of maritime history because it refuses to blink. It looks directly at the worst things humans are capable of when pushed to the edge and asks us to empathize with them anyway. It’s a story about whales, sure. But mostly, it’s a story about how fragile our civilization really is when the water starts rising.

To get the most out of the experience, start by reading the first three chapters to understand the "whaling machine" of Nantucket. Then, find a copy of the 1821 Owen Chase narrative to compare how the survivors "spun" the story versus the objective facts Philbrick uncovers. Finally, visit the Nantucket Historical Association's digital archives to see the actual artifacts recovered from the era, which bring the physical world of the Essex into sharp, haunting focus.