You've heard it at a thousand funerals. Or maybe you remember your grandmother humming it while she snapped green beans on the porch. The In the Garden lyrics are so deeply embedded in the American psyche that we almost forget someone actually sat down and wrote them. It wasn't some ancient monk or a medieval poet. It was a pharmacist from New Jersey named C. Austin Miles.

The year was 1912.

Miles wasn't just a guy who filled prescriptions; he was a prolific songwriter for the Hall-Mack publishing company. One day, he found himself sitting in a cold, dark "darkroom" where he developed photography—his hobby. He had his Bible open to John 20. He was reading about Mary Magdalene at the tomb. Suddenly, he felt like he was right there in the garden with her.

He wrote the words in a fever dream of inspiration.

The melody followed soon after. He wanted something that felt like a "stepping" rhythm, a physical walk. Most people don't realize that the song was a massive commercial hit long before it was a church staple. It was one of the first "superstar" recordings of the early 20th century, popularized by the baritone Homer Rodeheaver during the massive Billy Sunday evangelistic campaigns.

Why the In the Garden lyrics feel different than other hymns

If you look closely at the text, it’s remarkably intimate. Honestly, it's almost romantic in a way that made some stuffy theologians uncomfortable back in the day.

"And He walks with me, and He talks with me, And He tells me I am His own..."

There is no mention of the cross here. No mention of sin, redemption, or the blood of Christ. It’s entirely focused on the personal, mystical experience of a single individual meeting the divine in a quiet, dew-drenched garden. This is why the song resonates so heavily with people who aren't necessarily "religious" but consider themselves "spiritual." It’s about a private moment. It's about being seen.

Critics in the early 1900s actually hated it. They called it "sentimental" and "erotic." Some church leaders thought it was too focused on the self and not enough on the community of the church. But the public didn't care. They loved the idea of a God who would take a walk with you in the morning mist.

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

The John 20 Connection

To really understand the In the Garden lyrics, you have to go back to that scene in the Gospel of John. Mary Magdalene is weeping. She thinks someone has stolen the body of Jesus. She sees a man she thinks is the gardener.

"Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have put him..."

Then he says one word: "Mary."

That’s the "voice" Miles is talking about in the song—the one that’s "so sweet the birds hush their singing." It’s that moment of recognition. Miles wasn't trying to write a sermon; he was trying to capture the emotional shock of a dead friend being alive.

The unexpected legacy of a 1912 poem

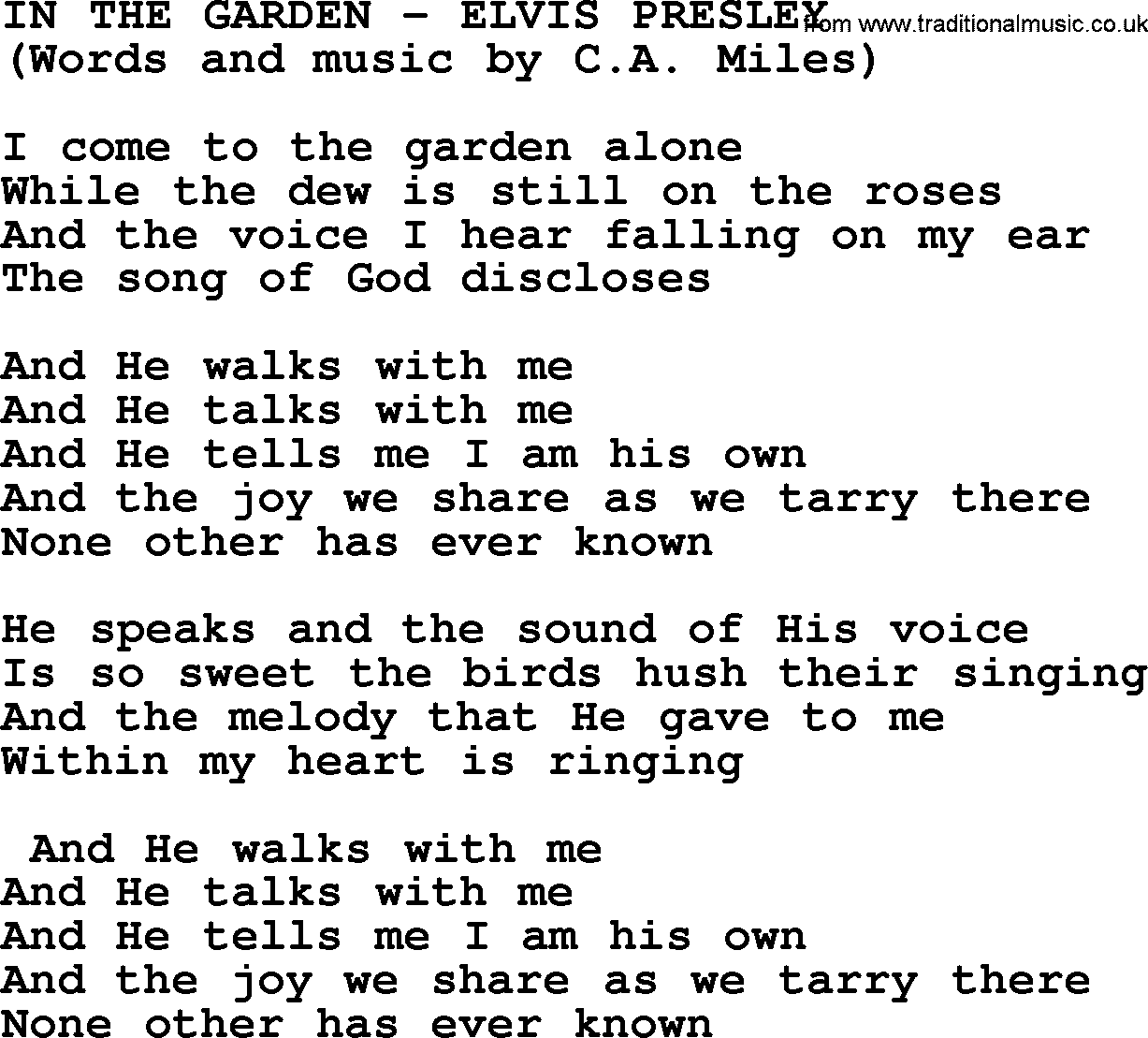

The song has been covered by everyone. Elvis Presley gave it a haunting, stripped-back treatment. Johnny Cash made it sound like a weary traveler finding rest. Even Willie Nelson and Alan Jackson have taken a crack at it.

The staying power of these lyrics is kind of wild when you think about how many thousands of hymns have been written and forgotten. Part of it is the sheer simplicity of the imagery. You don't need a degree in divinity to understand a garden, the dew on the roses, or the sound of a voice. It’s accessible.

Interestingly, C. Austin Miles didn't think this was his best work. He wrote hundreds of songs, but this one "wrote itself" in about ten minutes.

Does the song mean what you think it means?

There's a common misconception that the song is about the Garden of Eden. It isn't. It’s strictly about the Garden of Gethsemane or, more accurately, the garden tomb of Joseph of Arimathea.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Another weird bit of trivia: The song was used as a "signal" in certain historical contexts. Because it was so ubiquitous, it could be hummed or whistled as a sign of shared faith or even as a code in places where overt religious expression was frowned upon.

A closer look at the verses

The first verse sets the scene: "I come to the garden alone, while the dew is still on the roses." This isn't just a pretty picture; it’s a specific time—dawn. In the 1910s, "the garden" was a place of refuge from the industrial noise of the city. Miles was living in a rapidly changing America. The world was getting louder, faster, and dirtier. The lyrics offered a psychological escape into a quiet, pre-industrial space.

The second verse is where things get "supernatural."

"He speaks, and the sound of His voice is so sweet the birds hush their singing, and the melody that He gave to me within my heart is ringing."

This is the part that really hooked the Victorian-era listeners. It tapped into the Transcendentalist vibe—the idea that God is found in nature, not just in a cold stone building.

Then you have the bridge/chorus. It’s repetitive for a reason. In the early days of radio and phonographs, catchy choruses were essential. Miles was a businessman as much as a believer. He knew that a soaring, easy-to-remember refrain would sell sheet music. And boy, did it sell. It became one of the most profitable pieces of religious music in history.

Why it still hits hard today

Honestly, we live in a world where everyone is "connected" but nobody is actually talking. The In the Garden lyrics promise the opposite: a deep, one-on-one conversation where you are the sole focus. It’s an antidote to loneliness.

You’ve probably noticed it’s a polarizing song. If you talk to a high-church music director, they might roll their eyes at the "saccharine" melody. But if you talk to someone who has just lost a parent, they’ll tell you it’s the only song that brings them peace. That’s the power of Miles’ writing. He bypassed the brain and went straight for the gut.

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

The Pharmacist's Secret

C. Austin Miles died in 1946. He didn't die a wealthy man, despite the success of his songs, because the copyright laws of the time were a bit of a mess. But he didn't seem to mind. He often told people that he was just the secretary; the "Author" was the one he met in the darkroom that day in 1912.

Whether you view it as a theological masterpiece or just a catchy folk tune, you can't deny its impact. It has survived world wars, the rise of the internet, and the total transformation of the music industry.

Practical ways to use the song today

If you’re looking to use this song for a service or a personal project, keep these things in mind:

- Tempo matters. Most people drag this song out until it feels like a dirge. Try picking up the pace. Remember, Miles wanted it to feel like a "walk." It should have a bit of a lilt.

- Contextualize it. If you're performing it or sharing the lyrics, mention the Mary Magdalene connection. It changes the way people hear the words "He walks with me." It’s not just a general feeling; it’s a specific moment of resurrection.

- Try different arrangements. The standard organ-heavy version is classic, but the song really shines with a simple acoustic guitar or even a solo cello. The lyrics are intimate, so the music should be too.

Check the copyright status before using it for commercial recordings. While the original 1912 version is in the public domain in many jurisdictions, specific later arrangements or recordings might still be under license.

To truly appreciate the In the Garden lyrics, try reading them without the music. Strip away the Sunday morning memories. Look at them as a poem written by a man in a darkroom who just wanted to feel a little less alone. It’s a song about the human desire for a presence that stays "though the night around me be falling."

The next time you hear that familiar opening line, remember the pharmacist in Jersey. Remember the photography darkroom. And remember that sometimes, the simplest words are the ones that end up living forever.

Actionable Insights for Using "In the Garden"

- For Worship Leaders: Pair the song with a reading from John 20:1-18 to ground the "sentimental" lyrics in their original biblical context. This helps bridge the gap for those who find the song too subjective.

- For Musicians: Focus on the 6/8 time signature. It’s a waltz. If you play it too straight (4/4), it loses the "stepping" quality that C. Austin Miles intended.

- For Personal Reflection: Use the lyrics as a meditative guide. The progression from the "garden" to "the voice" to "the joy of our tarrying" follows a classic path of contemplative prayer—entering silence, listening, and then experiencing a sense of presence.

- For Family History: If this was a favorite of a loved one, look up the 1910s-1920s recordings by Homer Rodeheaver. Hearing it in its original "hit" style can provide a fascinating window into the world your ancestors lived in.