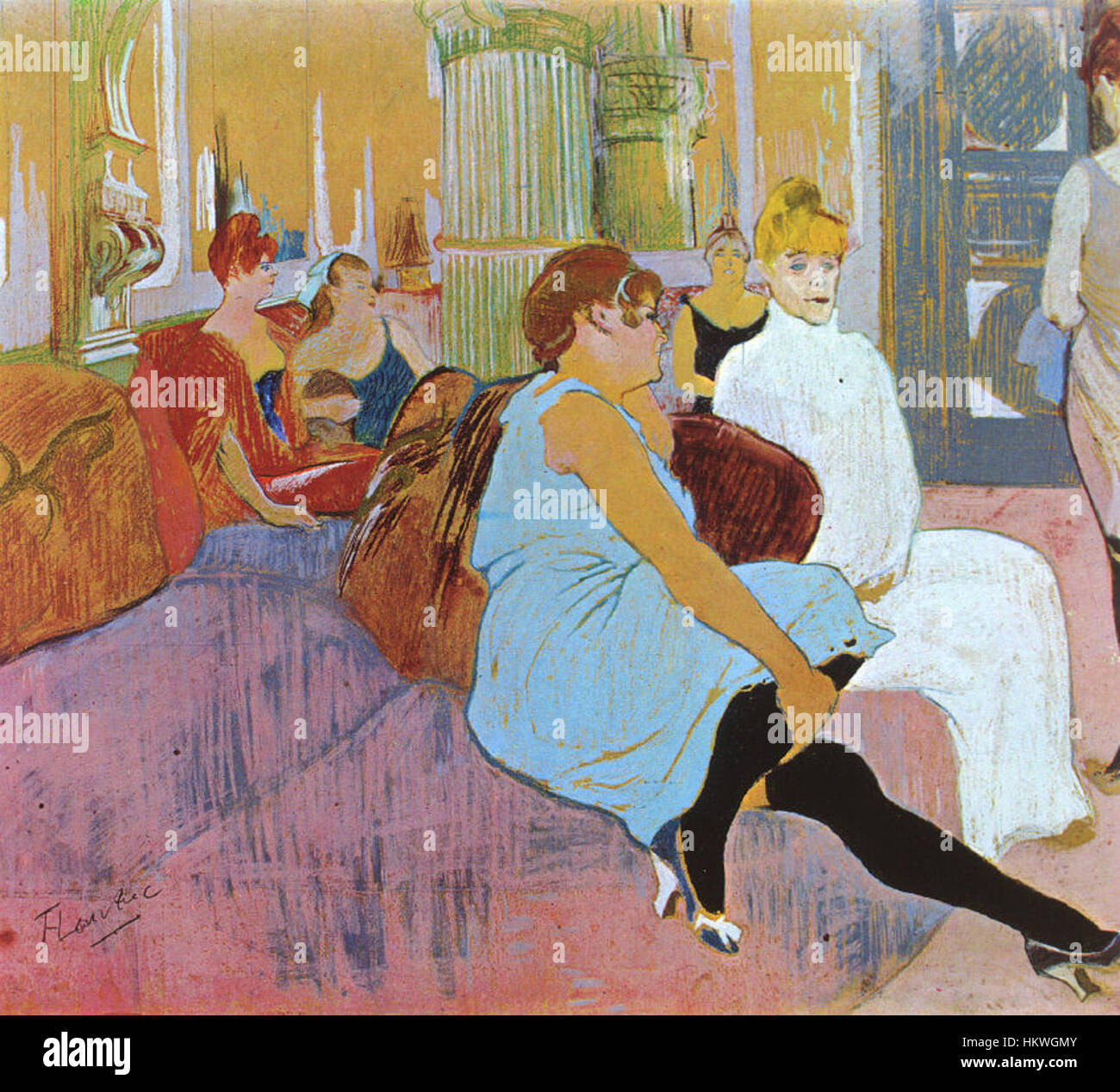

You can almost smell the stale perfume and the heavy, stagnant air of 19th-century Paris just by looking at it. Honestly, In Salon of Rue des Moulins isn't exactly a "pretty" painting in the traditional sense, but it is one of the most honest things ever put on canvas. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec didn't just walk into a brothel, snap a mental photo, and leave. He lived there. He was a fixture.

While other artists were busy painting pretty landscapes or idealized nymphs in the woods, Lautrec was sitting on velvet sofas in the Rue des Moulins, sketching women who were bored out of their minds. It’s raw. It’s gritty. It’s also surprisingly tender if you look close enough.

The Reality Behind the Red Velvet

The Rue des Moulins was one of the most "luxurious" brothels in Paris—a maison close. But "luxury" is a relative term when you're talking about the 1890s. This wasn't some glamorous den of sin. For the women living there, it was a job characterized by endless, soul-crushing waiting.

Lautrec captures this specific brand of boredom perfectly. Look at the women in the painting. They aren't "performing" for the male gaze. They aren't posing. They are slumped. They are staring into space. One is lifting her shift, perhaps for a medical inspection or just out of habit. It’s the sheer mundanity that hits you first.

Most people expect a painting of a brothel to be scandalous. This isn't scandalous; it's exhausted. Lautrec spent weeks at a time living in these houses, specifically the one at 24 Rue des Moulins. He wasn't there as a voyeur in the typical sense. He was an outcast himself—stunted in growth, physically disabled, and rejected by the high society he was born into. In the salon, he found a weird kind of kinship. The women accepted him because he didn't judge them.

Composition That Breaks the Rules

The perspective in In Salon of Rue des Moulins is intentionally awkward. It feels cramped despite the large room. The giant, ornate columns and the plush red walls should feel expensive, but instead, they feel like a cage.

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Lautrec uses a technique that’s almost like a wide-angle lens. You’ve got Mireille, the woman in the foreground, who looks almost regal despite the context. Then you have the others, fading into the background. The colors are muted despite the heavy reds and purples. It’s that "Peinture à l’essence" style—oil thinned with turpentine—which gives it a matte, chalky look. It looks like a memory that’s starting to go dusty.

There is no "center" to the painting. Your eyes dart from the woman adjusting her clothes to the one staring blankly at the wall. This lack of a focal point mirrors the aimless lives of the subjects. They are just... existing.

Why 1894 Was a Turning Point

By 1894, when he finished this large-scale work (it’s about 111 by 132 centimeters), Lautrec was at the height of his powers but also the depth of his alcoholism. You can see a shift in his work here. He moved away from the frantic energy of the Moulin Rouge posters—the high kicks and the bright yellows—and toward something much more psychological.

The Salon of Rue des Moulins represents a peak in Post-Impressionism because it abandons the "pretty" light of Monet for a psychological truth. It’s the "anti-Olympia." While Manet’s Olympia stared back at the viewer with a challenge, Lautrec’s women don't even bother to look. You are invisible to them.

The Myth of the "Glamorous" Paris Nightlife

We have this tendency to romanticize Belle Époque Paris. We think of "Midnight in Paris," sparkling champagne, and Cancan dancers.

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

The reality? It was tough.

Prostitution was legal but strictly regulated by the Police des Mœurs. These women were subjected to invasive weekly medical exams. They were often in debt to the "madam" of the house. Lautrec doesn't hide this. If you look at the sketches leading up to the final painting, he focuses heavily on the "inspection" aspect.

In the final version, the "Madam" is there, too. She sits stiffly, tucked away, the enforcer of the house rules. She looks like a Victorian grandmother, which makes the whole scene even more unsettling. The contrast between the formal, stuffy attire of the management and the semi-clothed state of the workers tells the whole story of class and exploitation without saying a word.

Seeing the Painting Today

If you want to see it in person, you have to head to the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, France. It’s his hometown. It’s a bit of a trek if you’re just staying in Paris, but honestly, it’s worth it. Seeing it in the context of his other sketches—the ones where he’s just capturing the way a woman brushes her hair or sighs—makes the big Salon piece feel much more intimate.

Critics at the time didn't really know what to do with it. It wasn't "erotic" enough for the creeps and it wasn't "moralistic" enough for the prudes. It just was. That's why it's a masterpiece. It refuses to give the viewer the satisfaction of a clear emotion. You feel sorry for them, but you also feel like an intruder.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

The Influence on Modern Art

You can draw a straight line from In Salon of Rue des Moulins to the works of Picasso’s Blue Period or even the gritty photography of Nan Goldin. Lautrec pioneered the idea that the "unworthy" subject matter—the backrooms, the tired workers, the outcasts—was the only thing worth painting.

He didn't want to paint queens. He wanted to paint the people who knew what it was like to be looked at but not seen.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific era or Lautrec’s style, don't just look at the finished oil paintings. The real magic is in the lithographs.

- Check out the "Elles" series: This is a set of 10 lithographs Lautrec did around the same time. It’s even more intimate than the Rue des Moulins painting. It shows the women waking up, washing, and eating breakfast. It’s the "day in the life" version.

- Visit the location: While the brothel at 24 Rue des Moulins is long gone in its original form, walking that street in the 1st Arrondissement of Paris gives you a sense of the geography. It was literally around the corner from the center of power and wealth.

- Look for the "ghosts" in the paint: Because Lautrec used thinned oil, parts of the cardboard or canvas often show through. This wasn't a mistake; it was a way to make the image feel fleeting and raw. When viewing his work, look for where he didn't paint.

- Study the body language: Next time you see a high-res version of the Salon painting, ignore the faces for a second. Look at the hands and the feet. The tension in the toes and the limpness of the hands tell the real story of the physical toll their work took.

Lautrec died at 36, burnt out by cognac and syphilis, but he left behind a record of Paris that no one else was brave enough to record. He didn't paint the Rue des Moulins because he wanted to be edgy. He painted it because, for a brief moment in history, that was the only place where he felt like he belonged. That sense of belonging, however tragic, is what makes the painting vibrate with life over a century later.