You’ve probably heard it. That somber, haunting melody usually played on a lone trumpet or sung by a choir during Remembrance Day or Memorial Day services. It’s the In Flanders Fields song, and honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle that it exists at all. Most people think of it strictly as a poem—a piece of Canadian literature written in the back of an ambulance during World War I. But the transition from ink on a page to a piece of music changed how we grieve.

It wasn't just one person who decided to set John McCrae’s words to music. Dozens did. But the versions that stuck—the ones that make your throat tighten up—managed to capture something specific about 1915 that we still haven't quite moved past.

The messy birth of a masterpiece

John McCrae didn't sit down in a quiet library to write. He was a surgeon. He was tired. He was surrounded by the literal blood and guts of the Second Battle of Ypres. On May 2, 1915, his friend Alexis Helmer was blown to bits by a shell. McCrae performed the burial service himself because the chaplain was busy elsewhere. He noticed how quickly poppies grew around the fresh graves.

The story goes that he scribbled the lines in a notebook while sitting on the rear step of an ambulance. Legend says he actually threw the poem away. A fellow officer supposedly salvaged it from the trash. Whether that's 100% true or just a bit of wartime mythology, the poem was eventually published in Punch magazine in December 1915. It was an instant hit. But it needed a voice.

Music followed fast.

Why the melody matters more than the meter

The poem has a very specific rhythm—it’s a rondeau. That means it’s repetitive and circular. When you turn it into the In Flanders Fields song, you’re dealing with a structure that is naturally mournful.

📖 Related: Casino Royale 2006 Free: Why Everyone Is Searching for This Bond Classic Right Now

Early composers like John Philip Sousa (yes, the "Stars and Stripes Forever" guy) actually tried their hand at it. Sousa’s 1918 version is fascinating because it’s not just a sad dirge; it has that military drive. But it didn't quite capture the "larks, still bravely singing" part. Then you have Charles Ives, an American composer who went a completely different route. His version is dissonant. It’s jarring. It feels like the chaos of the trenches. It doesn't let you sit comfortably in your seat.

The version you likely know (and why it works)

If you’re in a choir today, you’re probably singing the arrangement by Roger Emerson or perhaps the one by Alexander Tilley. These are the "standard" versions that schools and veterans’ groups gravitate toward.

Why? Because they lean into the "we are the Dead" section with a drop in volume. It’s ghostly.

- The Tempo: Most successful versions are slow.

- The Key: Usually minor, shifting briefly to major when mentioning the "glow" of the sunset.

- The Ending: This is the controversial part.

The final stanza of the In Flanders Fields song is basically a recruitment poster. "Take up our quarrel with the foe." In modern times, some people find this part uncomfortable. It’s a call to keep fighting. When it’s sung, that "quarrel" often sounds more like a sacred duty than a literal demand for more bayonet charges. This nuance is lost if you just read the text, but the music softens the edges of the pro-war sentiment, turning it into a plea for remembrance rather than a demand for vengeance.

The Great War's viral hit

Back in 1917, sheet music was the "Spotify" of the era. If you wanted to hear a song, you bought the paper and played it on your piano at home. The In Flanders Fields song was essentially a viral sensation. Families whose sons were never coming back from France bought this music to feel a connection to those "rows" of crosses.

It provided a bridge between the front lines and the living room.

Misconceptions about the "Official" Song

There is no "official" version. That’s a common mistake. Because the poem is in the public domain, anyone from Leonard Cohen to a high school garage band can (and has) put it to music.

Interestingly, Leonard Cohen’s recitation—while not a "song" in the traditional sense—is often played over musical beds. His gravelly, deep voice captures the "short days ago we lived" line with more weight than a polished soprano ever could.

Does it still resonate?

Critics sometimes say the poem is dated. They argue it glorifies war. But the song version persists because it taps into a universal truth: we are terrified of being forgotten.

The poppies aren't just flowers in the song; they are a heartbeat.

When a choir sings "Sleep in Flanders fields," they aren't just singing about 1915. They are singing about the fragility of life. It’s why it’s played at funerals for people who never even served in the military. It has transcended the trenches.

Beyond the choir: Modern adaptations

In recent years, the In Flanders Fields song has migrated into some weird places. You’ll find it in video game soundtracks (like Battlefield 1) and even in folk-rock covers.

The folk versions are actually some of the most authentic. If you listen to a version with a simple acoustic guitar and a raw vocal, it feels much closer to what McCrae might have heard in his head—not a grand orchestra, but a quiet, desperate hum amidst the noise of the guns.

- The Choral Powerhouse: Usually 4-part harmony (SATB). This is the "wall of sound" version.

- The Solo Bugle/Voice: Often performed at the Cenotaph.

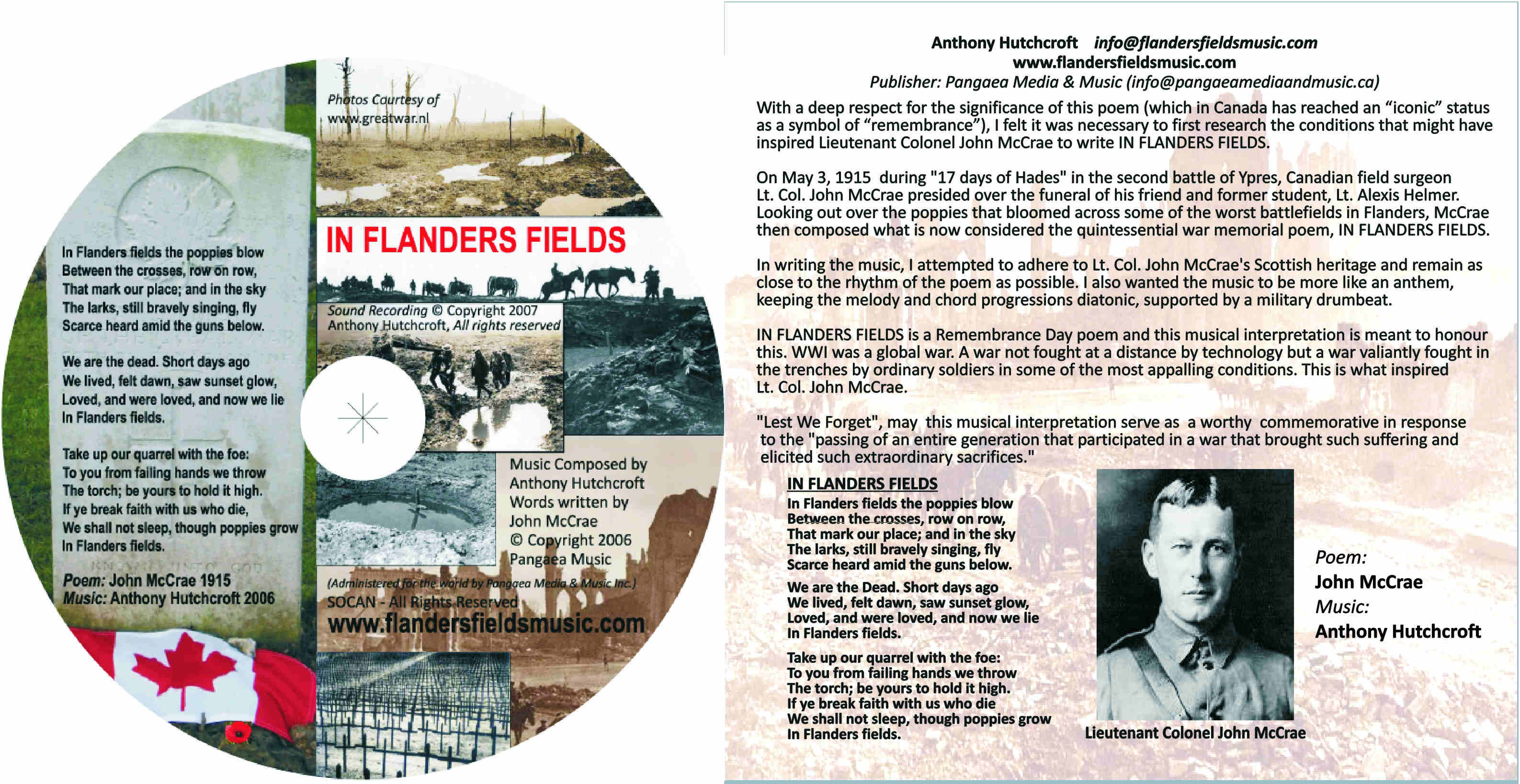

- The Contemporary Re-imagining: Artists like Anthony Hutchcroft have tried to give it a more modern, cinematic feel.

The technical challenge of singing McCrae

Ask any tenor. The middle section is a nightmare.

"We are the Dead. Short days ago / We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow."

The phrasing requires huge breath control because you can't break the line. If you breathe in the middle of "sunset glow," you ruin the imagery. You have to hold that "glow" while the accompaniment shifts underneath you. It’s meant to feel like the sun is actually setting.

Also, the "Poppies blow" line needs to be airy. If it’s too heavy, the song loses its ghost-like quality. Most directors tell their singers to imagine they are the grass itself, swaying.

Actionable steps for exploring the music

If you’re looking to truly understand the In Flanders Fields song, don't just listen to the first YouTube result.

👉 See also: Why Foo Fighters The Pretender Lyrics Still Hit So Hard Twenty Years Later

- Compare two extremes: Listen to the Charles Ives version (it’s weird, be prepared) and then listen to a standard choral arrangement by Roger Emerson. Notice how the first feels like a nightmare and the second feels like a prayer.

- Check the sheet music: If you play piano, look for the 1910s-era sheet music on sites like the Library of Congress. The cover art alone tells a story of how the song was marketed to a grieving public.

- Read the medical context: Before you sing it, read about John McCrae’s work at the dressing station. It changes how you interpret the "quarrel" line. It wasn't about politics for him; it was about the sheer volume of loss he saw on his operating table.

The In Flanders Fields song isn't just a piece of music. It’s a 110-year-old conversation between the dead and the living. Whether you like the military versions or the soft folk covers, the core message remains: the dead are watching us to see if we'll keep the faith. It's a heavy burden for a simple melody, but that's exactly why we haven't stopped singing it.

To get the most out of this history, look for recordings by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir for sheer scale, or seek out the Canadian Chamber Choir for a more intimate, nationalistic interpretation that honors McCrae's specific roots.