It was 1968. Music was changing, sure, but nobody was quite ready for seventeen minutes of a fuzzy, repetitive organ riff and a drum solo that felt like it lasted an entire presidency. When you think about In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly, you’re thinking about a song that basically broke the radio. Before this track dropped, pop songs were three minutes of neat, tidy melodies. Afterward? Everything was different.

Honestly, the story of how it was made is way messier than the polished "classic rock" narrative we’ve been fed for decades. It wasn’t a grand master plan. It was a happy accident born out of exhaustion and a lot of cheap wine.

Doug Ingle, the band's keyboardist and vocalist, was the one who wrote it. The legend—which is actually true, by the way—is that he was so drunk on Red Mountain wine when he played it for drummer Ron Bushy that he couldn't even enunciate the intended title. It was supposed to be "In the Garden of Eden."

Imagine that.

If Ingle had been sober, we’d be talking about a flowery, psychedelic hippie tune with a biblical name. Instead, Bushy wrote down the phonetic slurs he heard: In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. It sounded mystical. It sounded heavy. It sounded like something from another planet. And so, rock history was accidentally pivoted by a guy who couldn't find his tongue.

The Myth of the Seventeen-Minute Jam

Most people assume the song is long because they were "experimental." That’s giving them too much credit. The real reason the track takes up the entire second side of the album is that the band was waiting for their producer, Jim Hilton, to show up at the studio.

They were just warming up.

They started playing the riff to get their levels right. The engineer, Don Casale, was smart enough to hit the "record" button while they jammed out. They just kept going because nobody told them to stop. When you listen to that sprawling middle section, you’re hearing a band literally killing time. You've got Erik Brann—who was only 17 years old at the time—shredding through guitar tones that felt way more aggressive than the "Summer of Love" vibe happening elsewhere in California.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

By the time the producer actually arrived, the "demo" was finished. He listened to it and realized they couldn't possibly do it better. It was raw. It was slightly out of tune in places. It was perfect.

Why the Riff Stuck (and Why it Still Matters)

Why does this song still show up in The Simpsons, Home Alone, and every "Best of the 60s" compilation? It’s the riff. That D-minor descent is heavy. It’s got a chromatic, "evil" quality that would later become the blueprint for bands like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple.

If you look at the musical structure, it’s actually pretty simple. It doesn't rely on complex jazz chords or high-level theory. It’s primal.

- The opening organ blast creates an immediate sense of dread.

- The fuzzy guitar mirrors the bassline, creating a "wall of sound" effect.

- The drum solo—love it or hate it—was the first time a rock drummer was given that much real estate on a studio recording.

Ron Bushy’s solo wasn’t technically the most advanced thing ever recorded, but it was tribal. It moved people. In an era where music was becoming increasingly intellectual and "progy," In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly stayed in the dirt. It felt like a basement party.

The Commercial Shockwave

Atlantic Records didn't know what to do with a 17-minute song. You can’t play that on AM radio. You just can’t.

But then came the rise of FM radio. DJs at "underground" stations loved it because it gave them enough time to go outside and smoke a cigarette (or whatever else they were doing in 1968) while the record played. It became the anthem of the FM revolution.

Eventually, they cut a three-minute version for the "normals," but the damage was done. The album In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida stayed on the charts for 140 weeks. It was the first album in history to be certified "Platinum" by the RIAA. Think about that. Before Iron Butterfly, "Gold" was the highest honor. They literally had to invent a new award because this weird, drunken jam sold so many copies.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

It’s easy to mock the song now. The lyrics are basically nonexistent. The organ sounds like it belongs in a haunted house. But in 1968, this was the heaviest thing on the planet.

Misconceptions and the "Doom Metal" Connection

A lot of critics at the time hated it. They called it repetitive. They called it self-indulgent. And yeah, it is those things. But that’s exactly why it works.

Modern "Doom Metal" and "Stoner Rock" owe everything to this track. If you listen to a band like Sleep or Electric Wizard, you can hear the DNA of Iron Butterfly. That commitment to a single, crushing groove for an extended period of time started here.

People also forget how young the band was. Erik Brann was a kid. He wasn't some seasoned studio pro; he was a teenager with a fuzz box and an attitude. That youthful aggression is what keeps the song from feeling like a museum piece. It feels alive. It feels like it might go off the rails at any second.

How to Listen to it Today

If you’re going to revisit In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly, don’t bother with the "Single Version." It’s pointless. It’s like eating the crust of a pizza and throwing away the rest.

You have to hear the full 17:05.

Put on a good pair of headphones. Notice how the drums are panned. Listen to the way the organ and guitar fight for space. It’s a masterclass in 1960s "more is more" production.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

- Focus on the 6:30 mark: This is where the drum solo starts to get weird.

- Check the 13:00 mark: The way the band re-enters after the solo is one of the most satisfying "drops" in rock history.

- The Ending: It doesn't fade out; it crashes.

Actionable Takeaways for Rock Fans

If you're a musician or a fan of the genre, there are a few things you can actually learn from this weird moment in history.

First, don't over-polish your demos. Some of the greatest records ever made happened when the band thought the "real" recording hadn't even started yet. Capturing a vibe is more important than capturing perfection.

Second, embrace the mistake. If Doug Ingle hadn't been slurring his words, we would have had a generic song about a garden. Instead, we got a legendary piece of gibberish that defined an era.

Finally, understand the context. To really appreciate what Iron Butterfly did, you have to listen to what else was on the charts in 1968. While everyone else was singing about sugar and honey, these guys were playing the soundtrack to a fever dream.

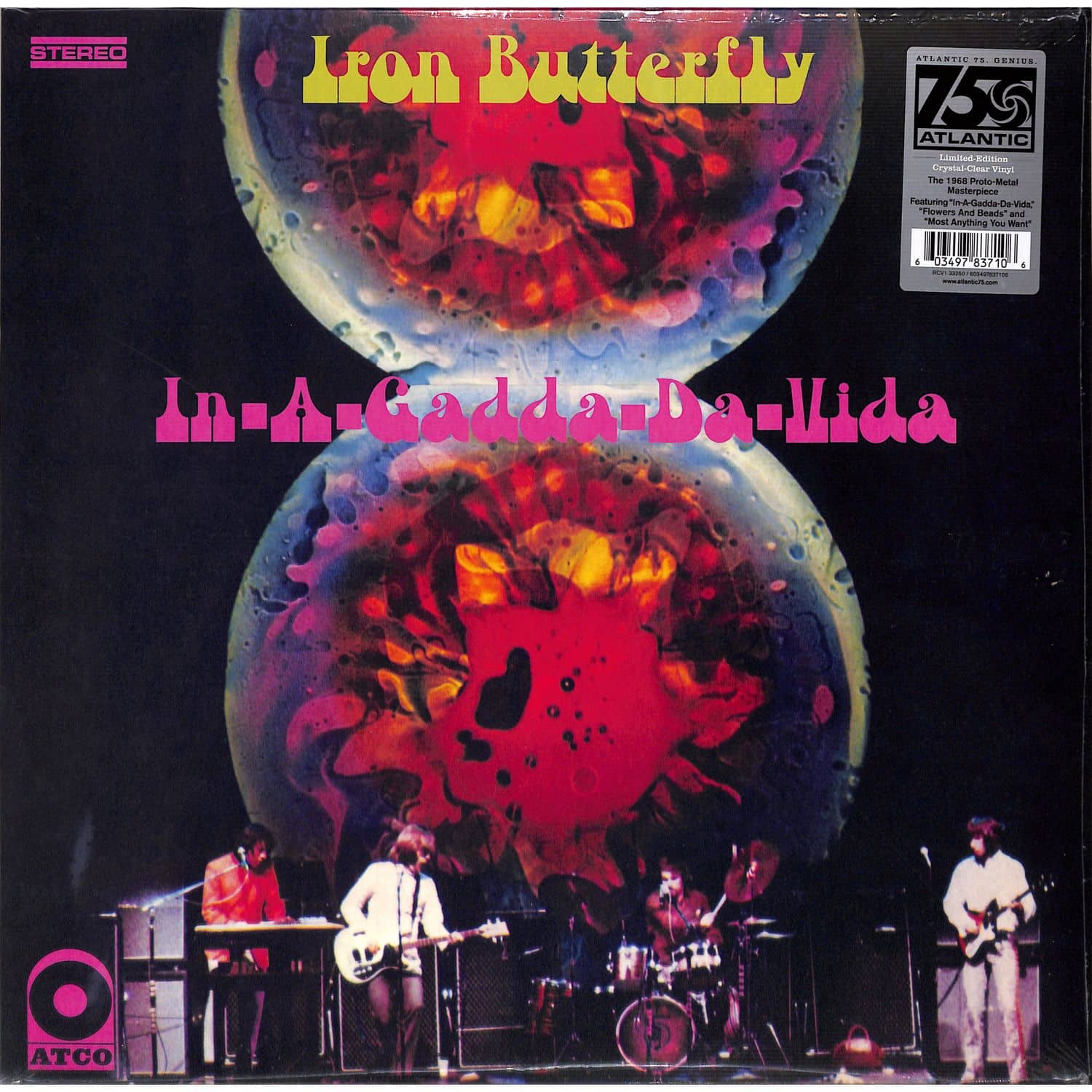

Go find the original vinyl if you can. The digital remasters are fine, but there’s something about the hiss and pop of a physical record that makes that D-minor riff feel even heavier. It’s not just a song; it’s a time capsule of a moment when rock music decided it didn't want to be polite anymore.

Next Steps for Deep Listeners:

- Compare the studio version to the live version on Live (1970) to see how much faster they played it once they were sober.

- Track down the 1995 "Deluxe Edition" for the clearest audio of the drum solo’s various percussion layers.

- Listen to Black Sabbath’s "Master of Reality" immediately afterward to see how the "Iron Butterfly blueprint" evolved into 70s metal.