It happened fast. One minute, South Korea was a stable, high-tech democracy; the next, soldiers were rappelling onto the roof of the National Assembly. Honestly, the impeachment of the South Korean president in late 2024 felt like a fever dream. If you weren't glued to the news on December 3, you missed the night that almost broke Seoul.

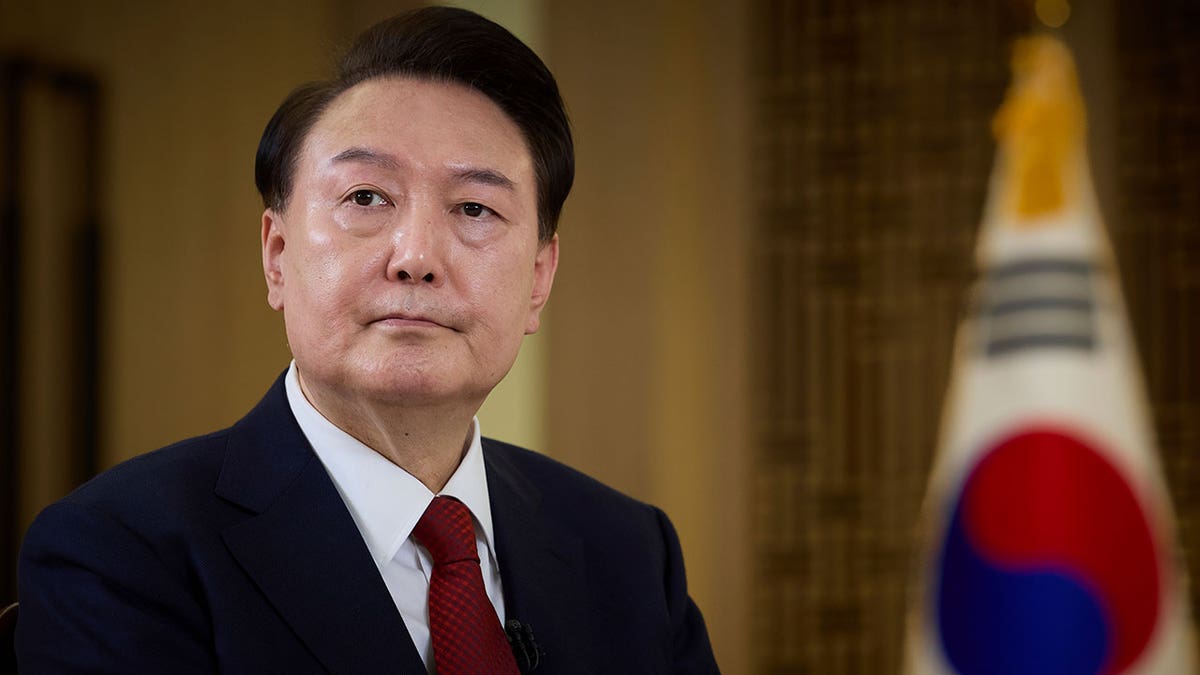

President Yoon Suk Yeol, a former "star prosecutor" who rose to fame by putting his predecessors in jail, suddenly found himself on the other side of the handcuffs. He declared emergency martial law at 10:25 PM. He called the opposition "anti-state forces." Basically, he tried to pause democracy because he was losing a budget fight.

It backfired. Spectacularly.

By 4:30 AM the next morning, the decree was dead. Lawmakers had hopped fences and pushed through lines of special forces to vote it down. But the political damage was permanent. That six-hour stunt triggered a chain reaction that ended with a unanimous 8-0 ruling from the Constitutional Court on April 4, 2025, stripping him of his title for good.

The Martial Law Mess That Started It All

You’ve got to understand how weird this was. South Korea hasn't seen martial law since the 1980s. When Yoon went on TV, people weren't sure if it was a prank or a coup. He claimed he was protecting the "liberal democratic system" from pro-North Korean elements.

✨ Don't miss: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

In reality? He was stuck. His approval ratings were hovering in the low teens. The opposition held a massive majority in the National Assembly. They were slashing his budget and impeaching his cabinet members. He felt cornered. So, he pulled the emergency brake.

But here is what most people get wrong: martial law isn't a "get out of jail free" card in Korea. The Constitution is very specific. Article 77 says the president can declare it, but Article 77, Clause 5 says if the National Assembly votes to lift it, the president must comply.

190 lawmakers made it into the hall. They voted 190-0 to kill the decree. Yoon was legally checkmated in under three hours.

Two Votes, One Goal

The impeachment of the South Korean president wasn't a one-and-done deal. It took two tries in the National Assembly to actually suspend him.

🔗 Read more: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

- The First Try (Dec 7, 2024): This was a bust. Members of Yoon's own People Power Party (PPP) boycotted the vote. Without them, the assembly couldn't reach the 200-vote quorum (two-thirds of the 300 seats).

- The Second Try (Dec 14, 2024): This time, the vibe had shifted. Protests were massive. It came out that Yoon had allegedly ordered the arrest of top politicians—including the leader of his own party, Han Dong-hoon. That was the breaking point. Twelve PPP members defected. The motion passed 204-85.

The moment the gavel hit, Yoon's powers were frozen. Prime Minister Han Duck-soo became the acting president.

How the Law Actually Works (The Boring but Important Part)

In the US, impeachment is mostly a political circus in the Senate. In South Korea, it's a legal trial. Once the National Assembly votes "yes," the case goes to the Constitutional Court. They have 180 days to decide if the president actually broke the law or the Constitution.

While the court deliberates, the president is basically a ghost. They stay in the Blue House (or the new Yongsan office), they keep their security detail, but they can't sign a single piece of paper. They can't even fire a janitor.

Yoon’s defense team tried everything. They argued the country was in a "state of national emergency." They claimed the opposition was paralyzing the government. The court didn't buy it. They ruled that using the military to block lawmakers was a "grave violation" of the principle of popular sovereignty.

💡 You might also like: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Why Park Geun-hye was different

People always compare this to the 2017 ousting of Park Geun-hye. But that was about corruption and a "shaman" friend pulling strings. Yoon's case was about an actual insurrection. Prosecutors eventually sought the death penalty for him—though that's mostly symbolic in a country that hasn't executed anyone since 1997.

Life After the Gavel

When the court upheld the impeachment of the South Korean president in April 2025, the clock started ticking. By law, a new election must be held within 60 days.

This led to the June 2025 snap election, where Lee Jae-myung—Yoon’s biggest rival—finally took the presidency. It was a massive swing to the left. But even that wasn't simple. Lee had his own legal baggage, showing just how messy Korean politics can get.

The fallout you should know about:

- Military Shakedown: A bunch of generals and police chiefs were arrested. They were the ones who sent the troops to parliament.

- Acting President Chaos: Even the acting president, Han Duck-soo, was impeached for a bit by the opposition. It was a total leadership vacuum for weeks.

- Economic Jitters: The Won tanked. Investors hate it when soldiers are roaming the streets of a global semiconductor hub.

What This Means for You

If you’re watching South Korea from the outside, don't just see this as "another political scandal." It’s actually a weirdly hopeful story about how strong their institutions have become. In the 70s, those soldiers would have stayed. In 2024, they were kicked out by a vote and a court ruling.

Actionable Insights for Following the Story:

- Track the Criminal Trials: The impeachment only removed Yoon from office. Now, he faces separate criminal trials for insurrection and abuse of power. Watch for news out of the Seoul Central District Court.

- Monitor the New Administration: President Lee Jae-myung’s policies on North Korea and the US are the polar opposite of Yoon's. Expect a shift away from the hardline stance against Pyongyang.

- Watch the "Third Force": Small parties like the Rebuilding Korea Party gained a lot of steam during the protests. They are the new kingmakers in the National Assembly.

The lesson here? In South Korea, the president has a lot of power—right up until they try to use it against the people who gave it to them.

Next Steps to Stay Informed:

- Check the latest rulings from the Seoul Central District Court regarding the insurrection charges against former military leaders.

- Review the 2026 budget proposals from the Lee Jae-myung administration to see how they are reversing Yoon-era fiscal policies.