You’ve seen them. The glowing, gold-saturated images of the Valley of the Kings that pop up on every travel influencer's feed or in the glossy pages of a National Geographic spread. They’re stunning. Honestly, though? They’re often kinda misleading. When you’re actually standing in the Wadi el-Muluk, the "Gateway to the Afterlife" near Luxor, the reality is much more grit, dust, and overwhelming scale than a filtered JPEG can ever really capture.

The valley is a scorched limestone canyon. It’s hot. Brutally so. Most people expect a lush oasis because of the Nile nearby, but the Pharaohs chose this spot specifically because it was a natural fortress—a desolate, dry environment that helped preserve the bodies of the New Kingdom’s elite for millennia. When you look at high-resolution images of the Valley of the Kings today, you’re seeing the result of thousands of years of shifting sands and a century of intense archaeological restoration. But photos can’t smell the ancient, dry air or feel the sudden drop in temperature when you descend forty feet into a rock-cut tomb.

The Problem with Photography in the Tombs

For years, taking pictures inside the tombs was a big no-no. It was strictly forbidden. You’d have to smuggle a camera in like a spy or risk a hefty fine and an angry guard. Then, things changed. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities started allowing mobile phone photography for free, while professional gear still requires a pricey permit. This change flooded the internet with a new wave of images of the Valley of the Kings, mostly taken by tourists with iPhones.

While it’s great that we can document our trips, there's a downside. Flash photography is a legitimate enemy of ancient pigments. The vibrant blues, ochres, and reds on the walls of KV17 (the Tomb of Seti I) or KV9 (Ramesses V and VI) are incredibly sensitive. Light—even just the ambient light from thousands of visitors—causes a process called photodegradation. If you see a photo that looks unnaturally bright, it’s likely because the photographer pushed the exposure or used a flash they weren't supposed to. Real historical photography, like the haunting black-and-white plates captured by Harry Burton during the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, tells a much grittier, more honest story of the site’s ruggedness.

What the Cameras Often Miss

Digital sensors struggle with the "Egyptian Blue." This specific pigment, made from calcium copper silicate, often looks flat or overly neon in digital images of the Valley of the Kings. In person, it has a depth that feels almost three-dimensional. Also, the sheer claustrophobia of the steeper tunnels, like those in the tomb of Thutmose III, is hard to translate. You’re climbing down a metal ladder into a literal hole in the ground. It’s cramped. Most wide-angle shots make these chambers look like spacious hallways, but they are often tight, airless, and filled with the collective breath of fifty other tourists.

👉 See also: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

Beyond Tutankhamun: The Visual Power of KV17 and KV11

Everyone wants the "King Tut" shot. Honestly? His tomb, KV62, is tiny. It’s the smallest royal tomb in the valley because he died so young and they had to scramble to finish it. If you want the most impactful images of the Valley of the Kings, you have to look at the tombs of the long-lived pharaohs.

Seti I has arguably the most beautiful tomb ever carved. It’s nearly 450 feet long. The ceilings are covered in astronomical charts—the "Book of the Heavenly Cow" and the "Litanies of Re." When you see professional photos of this tomb, the detail is staggering. Every inch of the wall is carved in raised relief before being painted. Most tourists don't realize that the "white" background they see in photos is actually a layer of fine plaster called gypsum that was applied over the rough-cut limestone to create a smooth canvas for the artists.

Then there’s KV11, the tomb of Ramesses III. It’s famous for the "Harpers' Scene," showing two blind musicians. It’s one of those rare moments where ancient art feels human and relatable rather than purely religious or obsessed with the afterlife. If you’re searching for authentic visual records, look for the work of the Theban Mapping Project. They’ve done the heavy lifting of documenting these sites with surgical precision, creating 3D models and high-fidelity scans that put casual tourist snapshots to shame.

The Ethics of Capturing the Dead

We need to talk about the "Mummy Room" photos. For a long time, images of the royal mummies—Seqenenre Taa, Ramesses II, Seti I—were everywhere. There is a massive ethical debate here. Are these historical artifacts or are they human beings? Egypt recently moved many of these royals to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) in the "Golden Parade."

✨ Don't miss: Madison WI to Denver: How to Actually Pull Off the Trip Without Losing Your Mind

Taking images of the Valley of the Kings today often involves a choice: do you focus on the architecture and the art, or do you seek out the sensationalism of the remains? Most modern archaeologists, like Dr. Zahi Hawass or Dr. Salima Ikram, emphasize the importance of dignity. Many of the most famous photos of mummies you see online were taken decades ago when conservation standards were... let's say, "different." Today, there are strict bans on photographing the actual remains in many areas to maintain both the physical integrity of the bodies and a sense of respect.

The Impact of Modern Tourism on the Visual Landscape

If you look at images of the Valley of the Kings from the 1970s versus today, you'll notice a huge difference in the "infrastructure." Today, there are wooden walkways, glass barriers, and powerful LED lighting systems. These were installed to protect the floors from the literal millions of feet that walk through every year.

The humidity is the silent killer. Each visitor exhales moisture, and that moisture carries salts. The salts get into the limestone and then crystallize, which basically "pops" the paint off the walls. This is why you’ll often see large wooden fans or sophisticated ventilation systems in newer photos of the tombs. It’s not just for the comfort of the tourists; it’s a life-support system for the art.

How to Find "True" Images of the Valley of the Kings

If you’re a researcher or just a nerd for history, don't rely on Instagram. The best visual archives are often tucked away in university databases. The Griffith Institute at Oxford has an incredible collection of original excavation photos. Seeing the Valley through the lens of early 20th-century explorers gives you a sense of how much of it was buried under tons of rock and debris.

🔗 Read more: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

- The Met Museum's Archive: They have stunning high-res photos of the artifacts found in the valley.

- Theban Mapping Project: This is the gold standard for site plans and wall-by-wall photography.

- Journal of Egyptian Archaeology: For technical photos of recent discoveries.

Dealing with the Crowds and the Heat

If you’re planning to visit and want your own images of the Valley of the Kings, get there at 6:00 AM. Seriously. By 9:00 AM, the tour buses from Hurghada arrive, and the valley becomes a sea of umbrellas and selfie sticks. The light is also best in the early morning; the low sun hits the limestone cliffs and turns them a deep, burnt orange that looks incredible in photos.

Avoid using a flash. Just don't do it. Even if the guards aren't looking. Modern phone sensors are good enough to handle the low light of the tombs without it. Use a "Night Mode" or long exposure setting, but hold your breath so your hands don't shake. The result will be a much more "moody" and accurate representation of the tomb's atmosphere than a washed-out flash photo.

Actionable Tips for the Modern Explorer

Don't just take pictures of the walls. Look at the ceilings. The "Starry Ceilings" in tombs like KV9 are some of the most overlooked features in amateur photography. They represent the night sky, often with the goddess Nut arched over the world. Also, pay attention to the "unfinished" tombs. Some chambers were left mid-work when a Pharaoh died suddenly. These provide a fascinating "behind the scenes" look at how the artists worked—you can see the red grid lines used for proportions and the black "correction" marks made by the master artists.

When you're looking at images of the Valley of the Kings, remember that you’re looking at a site that has survived tomb robbers, floods, and 3,000 years of history. The best way to respect it is to document it thoughtfully. If you're buying postcards or books on-site, look for the ones produced by local Egyptian publishers—they often have access to angles and lighting that the big international firms miss.

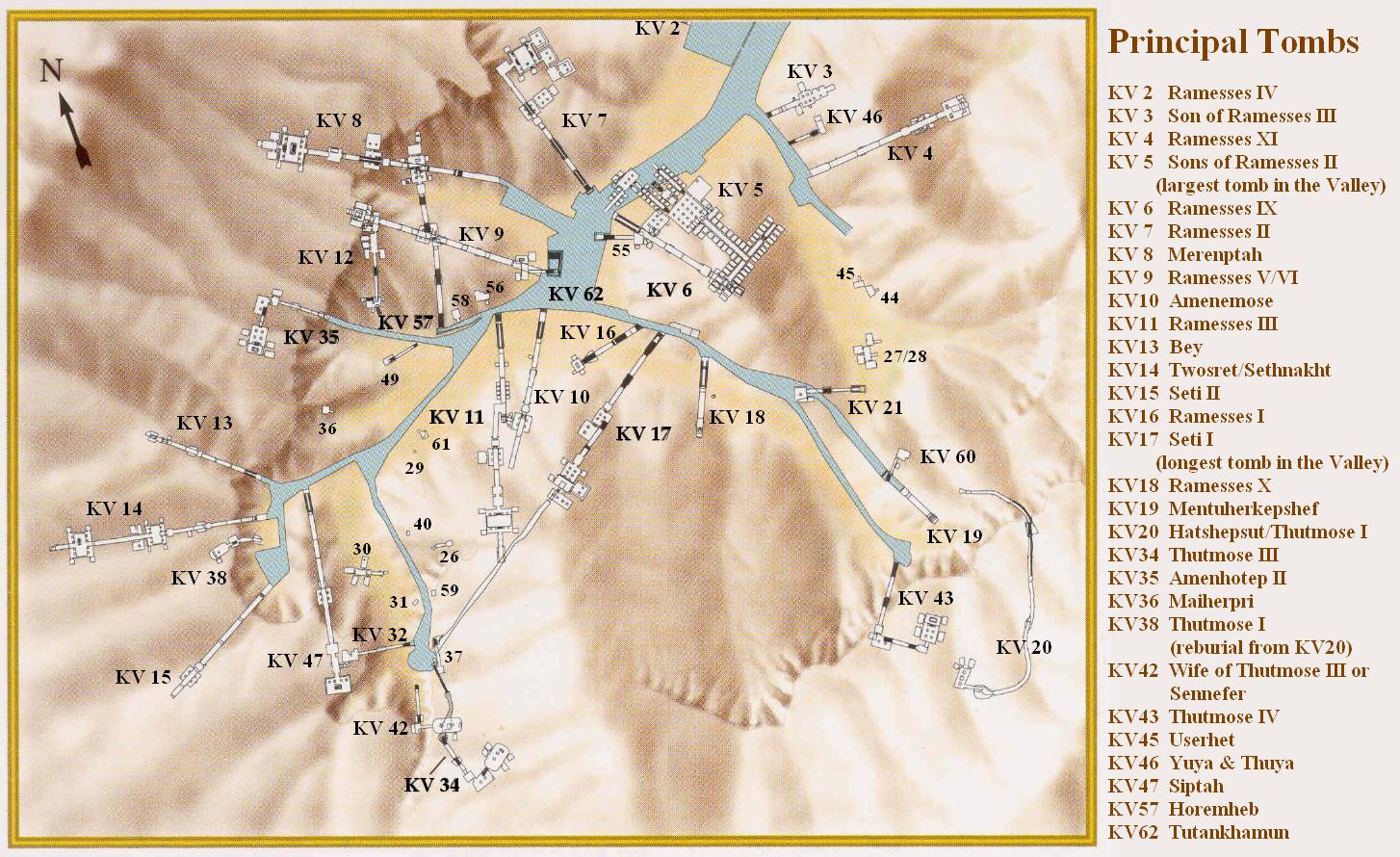

To truly understand the site, start by exploring the digital archives of the Theban Mapping Project to see the layout of the 60+ tombs. If you're traveling, invest in a high-quality circular polarizer filter for your camera lens; it helps cut the glare of the intense Egyptian sun on the white limestone. Finally, always check the official Ministry of Antiquities website before you go, as they frequently rotate which tombs are open to the public to prevent over-exposure to humidity. Seeing the Valley is a once-in-a-lifetime deal, so make sure the photos you take (or look at) reflect the actual majesty of the place, not just the "tourist version."