You’ve probably seen one before—maybe on a grainy X-ray or a glossy anatomy poster in a waiting room. It looks like a simple vacuum cleaner hose. A ridged, translucent tube tucked behind your heart. But images of the trachea are actually much weirder and more complex than those high school biology diagrams suggest. When medical professionals look at these visuals, they aren't just looking at a "windpipe." They are hunting for millimeters of deviation that could mean the difference between easy breathing and a medical emergency.

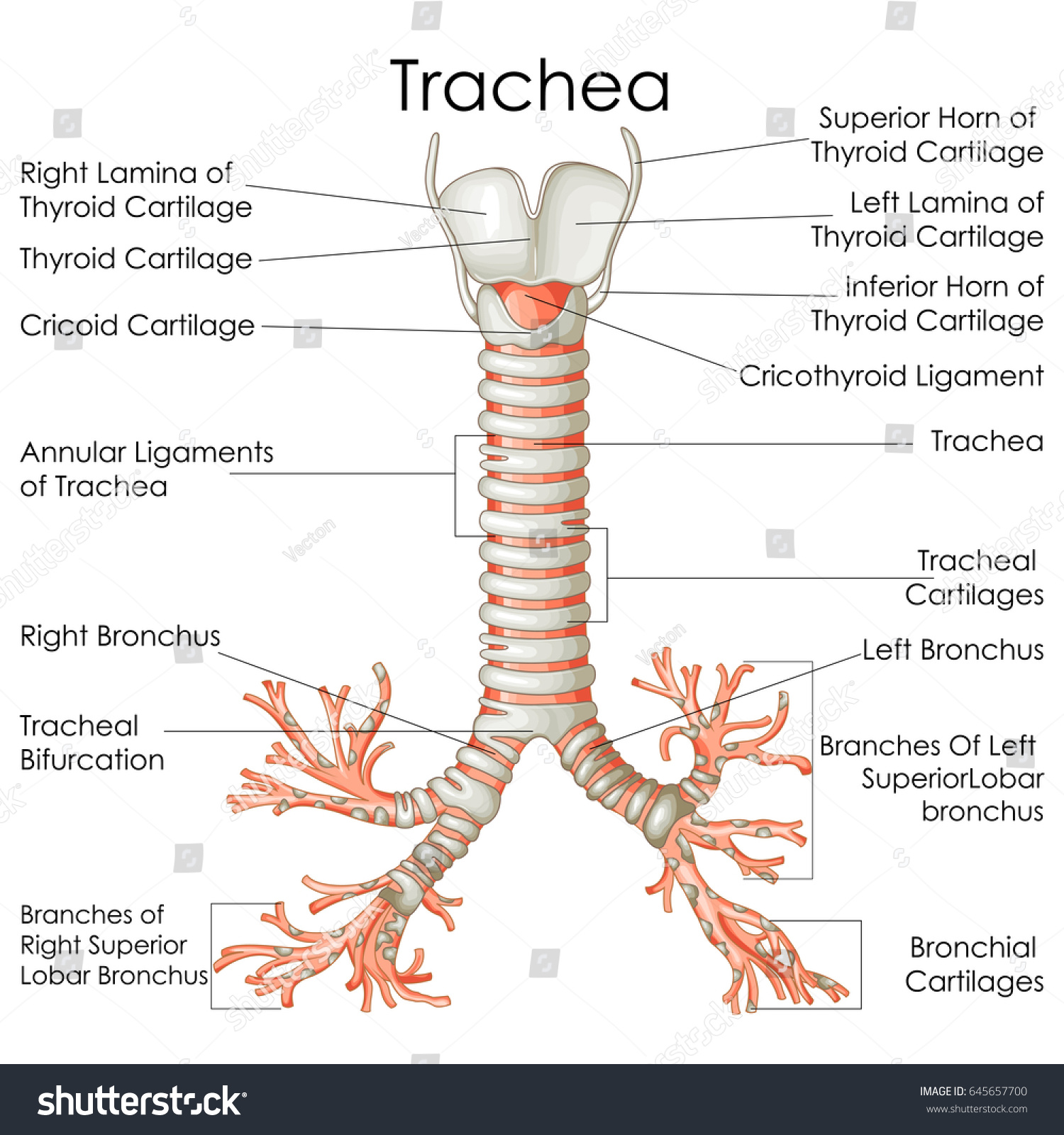

The trachea is roughly four inches long. It’s a masterpiece of structural engineering, honestly. It stays open under pressure thanks to C-shaped rings of hyaline cartilage. But here’s the kicker: those rings aren't complete circles. If they were, you couldn't swallow your food properly because the esophagus sits right behind it. When you see a cross-section image of the trachea, you’ll notice a flat back wall. That’s the trachealis muscle. It’s flexible for a reason.

Why Standard X-Rays Usually Fail to Show the Whole Picture

If you look at a standard chest X-ray, the trachea is often just a dark, vertical shadow. It’s filled with air. Air doesn't stop X-rays, so it shows up black. Radiologists call this the "air column." Most people think an X-ray gives a clear "photo" of the organ, but it’s more like a silhouette. If the trachea is shifted to the left or right—what doctors call tracheal deviation—it’s a massive red flag.

Often, the trachea isn't the problem itself in these images. It’s a victim of its neighbors. A massive tumor in the lung or a "tension pneumothorax" (a collapsed lung leaking air into the chest cavity) can push the trachea aside like a bully in a hallway. You can see this clearly in trauma bay imaging. It’s terrifying. One side of the chest is white or over-inflated, and that central air column is bent like a bow.

The Computed Tomography (CT) Revolution

CT scans changed everything for airway imaging. Instead of a flat, 2D shadow, we get "slices." Think of it like a loaf of bread. You can look at each slice individually. This is where images of the trachea become incredibly detailed. Doctors can measure the internal diameter to the millimeter. This is vital for conditions like tracheomalacia, where the cartilage softens and the airway collapses during exhalation.

👉 See also: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

On a CT scan, a healthy trachea looks like a perfect "O" or a slightly flattened "U." In patients with "Saber-Sheath Trachea," a condition often linked to COPD, the trachea narrows from side to side and elongates from front to back. It literally looks like the sheath of a sword. It’s a classic imaging finding that tells a doctor a lot about a patient’s lung health without even looking at the lungs themselves.

Bronchoscopy: The View from the Inside

Nothing beats the "first-person" view. A bronchoscopy involves threading a camera down the throat. The images captured here are wet, pink, and surprisingly rhythmic. You can see the mucosal lining. It should be shiny and pale pink. If it’s bright red and swollen, that’s inflammation.

One of the most striking things you'll see in these live images is the "carina." This is the fork in the road where the trachea splits into the left and right mainstem bronchi. It looks like a sharp, narrow ridge. In medical school, students are taught that the carina should be sharp like a knife's edge. If an image shows a dull, widened, or "blunted" carina, it often means there are swollen lymph nodes underneath it pushing up. This is a common sign in various cancers or sarcoidosis.

- Normal Carina: Sharp, distinct, V-shaped.

- Pathological Carina: Wide, flat, or obscured by secretions.

- Foreign Bodies: You’d be shocked at what ends up in these images. Peanuts, tooth fragments, and small toy parts are common "accidental" guests in the right mainstem bronchus because it’s wider and more vertical than the left.

Understanding Narrowing and Stenosis

Sometimes the trachea scars. This is called tracheal stenosis. It often happens after someone has been on a ventilator for a long time. The cuff of the breathing tube can irritate the delicate lining. When you look at images of the trachea in these cases, you see a "hourglass" deformity. The wide tube suddenly pinches down to a tiny hole.

✨ Don't miss: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

Imagine trying to breathe through a cocktail straw. That’s what it feels like. Radiologists use 3D reconstruction—taking CT data and turning it into a virtual model—to map this out before surgery. This allows surgeons to see exactly how many centimeters of the airway are damaged. They can even do a "virtual bronchoscopy," flying through a digital version of the patient's throat before they ever pick up a scalpel.

What People Get Wrong About Tracheal Images

There is a big misconception that "if the X-ray is clear, the airway is fine." That’s just not true. Standard imaging can miss "dynamic" collapse. This is where the trachea looks perfectly normal when you take a deep breath in (which is when X-rays are usually taken), but it collapses flat when you breathe out.

To catch this, doctors use "dynamic expiratory CT." They take images specifically while the patient is exhaling. It’s a game-changer for diagnosing chronic coughing or mysterious shortness of breath that doesn't show up on a resting scan. Honestly, the technology is incredible now, but it still requires a human eye to notice the subtle sagging of the posterior membrane.

Visualizing Pediatric vs. Adult Airways

Children aren't just small adults. Their tracheas are much more pliable. In a baby, the trachea is about the diameter of a drinking straw. Imaging a child's airway is a specialty in itself. Because their cartilage isn't fully hardened, it’s much easier for external things—like an enlarged blood vessel—to press on the airway and cause "stridor," that high-pitched gasping sound.

🔗 Read more: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

In pediatric images, radiologists look for the "steeple sign." This is seen on a frontal X-ray of the neck. The subglottic area narrows, making the air column look like a church steeple. It’s a classic hallmark of Croup. It’s different from epiglottitis, where the "thumbprint sign" shows a swollen flap of tissue at the very top of the airway. These visual cues are how ER doctors make split-second decisions.

Practical Steps for Understanding Your Own Imaging Results

If you or a loved one are looking at a radiology report mentioning the trachea, don't panic over every "slight deviation." Here is how to actually handle that information:

First, ask for the "coronal" and "sagittal" views. The coronal view is from the front; the sagittal is from the side. Looking at both gives you a 3D understanding of the space. If the report mentions "tracheal deviation," ask your doctor if it is "ipsilateral" (pulled toward a problem) or "contralateral" (pushed away from a problem). This helps pinpoint where the real issue lies.

Second, check for mentions of the "tracheoesophageal stripe." This is the thin line of tissue between the windpipe and the food pipe. If this stripe is thickened on an image, it can indicate infection or even early-stage esophageal issues.

Lastly, always request the actual image files (DICOM format) on a disc or via a portal. Seeing the "air column" yourself makes the doctor’s explanation much easier to follow. Look for that straight, dark line. It should be relatively central, maybe slightly to the right near the bottom because the aorta (the body's biggest artery) gives it a little nudge. That nudge is normal—it's called the "aortic impression"—and it’s one of the few "lumps" in a trachea image that isn't cause for concern.

Understanding these visuals isn't just for specialists. When you know what a healthy "air column" looks like, you become a much better advocate for your own respiratory health.