You’ve probably seen the red guy with the pitchfork. He’s on hot sauce bottles, sports mascots, and bad Halloween costumes. But when people start searching for images of the real devil, they aren't looking for a cartoon. They're usually looking for something "authentic"—a grainy CCTV still, a medieval woodcut, or maybe a shadowy figure captured on a doorbell camera.

Honestly? You're never going to find a selfie of Satan.

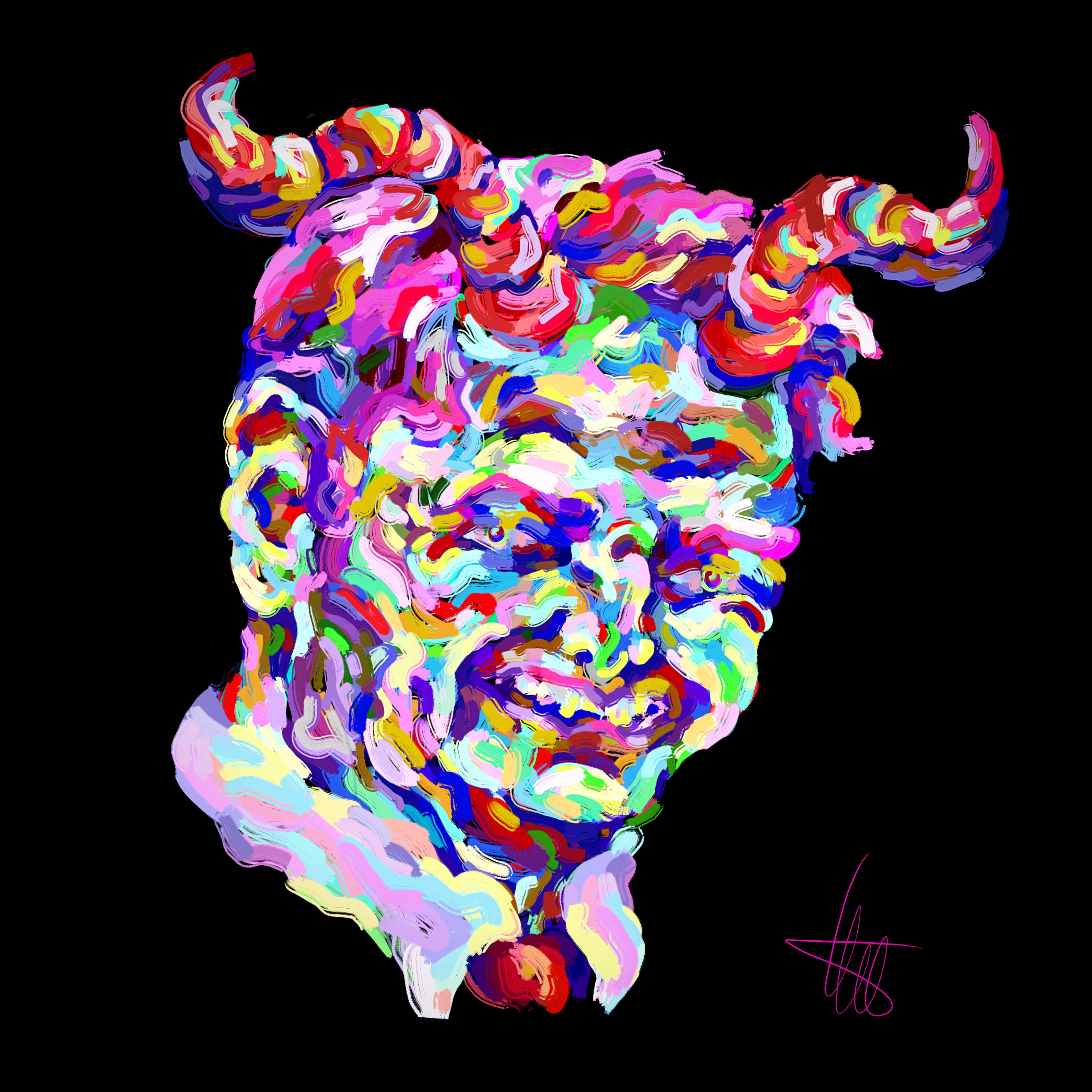

The search for a "real" image is a rabbit hole that leads through art history, theology, and a whole lot of psychological projection. We have this deep-seated human need to put a face on evil. We want a monster we can see, because if we can see it, maybe we can run away from it. But the history of how we’ve depicted this figure is way weirder than just a guy in a red suit.

Where the red suit actually came from

If you opened a Bible and looked for a description of a red man with horns and a tail, you’d be looking for a long time. It isn’t there. The "real" devil in early Christian thought wasn't a physical entity you could snap a photo of. He was a fallen angel, a spirit, or even a "roaring lion" looking for someone to devour.

The imagery we’re stuck with today is a mashup of ancient pagan gods. The horns and cloven hooves? Those were borrowed from Pan, the Greek god of the wild, mostly as a way for the early Church to say "these old gods are actually demons." The pitchfork is basically a downgraded version of Poseidon’s trident. It’s a branding exercise that’s lasted two thousand years.

By the time we got to the Middle Ages, artists like Giotto and Dante started getting specific. In the Inferno, Dante describes Satan as a giant, three-faced beast trapped in a lake of ice. Not fire. Ice. That’s a huge detail people miss. If you want images of the real devil as imagined by one of history’s greatest writers, he’s blue, freezing, and crying. It’s a pathetic image, not a scary one.

The modern obsession with "found" footage

Nowadays, the search has moved from cathedrals to the internet.

💡 You might also like: Why Pictures of Candles Burning Are Harder to Get Right Than You Think

Go to any paranormal forum and you'll see "leaked" photos. Usually, it's a blurry smudge in a basement or a reflection in a mirror. These are perfect examples of pareidolia. That's just a fancy way of saying our brains are hardwired to find faces in random patterns. We see a face in a burnt piece of toast; of course we’re going to see a demon in a low-resolution security feed.

There was that famous "demon on a hospital bed" photo that went viral years ago. Everyone swore it was a dark entity with bent legs standing over a patient. When the high-res version came out? It was a nurse’s leg and some medical equipment viewed from a weird angle.

Shadow people are another big one. People report seeing dark, humanoid silhouettes out of the corner of their eye. Sleep paralysis is the scientific culprit here. When your brain is half-awake but your body is locked down, your mind hallucinates "the intruder." It’s terrifying. It feels real. But it's an image generated by your synapses, not a digital camera.

How the "real" devil shifted from monster to human

Something changed during the Enlightenment. We stopped being scared of monsters under the bed and started being scared of the person next to us.

Look at Milton’s Paradise Lost. His Lucifer isn't a scaly beast. He’s a tragic, handsome, rebellious anti-hero. He says, "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven." This version of the devil—the sophisticated, seductive human—is what dominates our modern visual culture.

Think about Lucifer on Netflix or Al Pacino in The Devil’s Advocate. The "real" devil in these stories doesn't need a tail. He wears a tailored suit. This reflects a much scarier reality: the idea that evil doesn't look like a monster. It looks like us.

The iconography of the goat

We can't talk about images of the real devil without mentioning Baphomet. You've seen the goat-headed figure with wings and a torch between its horns. People often point to this as the "true" face of Satanism.

But here’s the kicker: Baphomet was created by Éliphas Lévi in 1854.

✨ Don't miss: Why Great Vegetarian Soup Recipes Often Fail (and How to Fix Them)

Lévi wasn't trying to draw the devil. He was trying to draw a symbol of "the absolute"—a balance of opposites (male/female, animal/human, dark/light). It was later adopted by the Church of Satan in the 1960s. It’s an iconic image, sure, but it’s a 19th-century occultist’s art project, not an ancient snapshot of a supernatural being.

Why we can't stop looking

There's a psychological weight to these images.

If we find a "real" image of a demon, it proves there’s a spiritual world. For a lot of people, even a scary spiritual world is better than a purely materialistic one where we’re just meat and bone.

Academic studies on "The Satanic Panic" of the 1980s show how quickly society can manufacture images of evil when it feels out of control. During that era, people "saw" devil-worshiping symbols in everything from heavy metal album covers to the logos of Procter & Gamble. None of it was real. But the fear was real, and it created a visual language that still haunts our search results today.

Analyzing the evidence

If you're looking for proof, you have to look at the source. Most "real" photos fall into three categories:

- Double Exposures: Old-school film tricks that look like ghosts or spirits.

- CGI and AI: It's 2026. You can generate a "hyper-realistic demon in a hallway" in four seconds. Digital artifacts are the new "orbs."

- The "Uncanny Valley": Images that look almost human but are slightly off. This triggers a primal fear response, making us label the image as "demonic" even if it's just a weirdly lit mannequin.

Real theologians will tell you that the devil is a "liar." If that's the case, why would he ever show his true face? He’d show you exactly what you wanted to see, or nothing at all.

What to do with this information

If you’re researching this for a project, or just because you went down a late-night YouTube hole, here’s how to handle the visual data:

- Cross-reference the metadata. If you find an "authentic" image online, use a reverse image search. Nine times out of ten, it’s a still from an obscure 2012 horror movie or a conceptual art piece from DeviantArt.

- Study the Art History. If you want to understand why the devil looks the way he does, look at the transition from the "beast" of the 1400s to the "gentleman" of the 1800s. It tells you more about human history than it does about theology.

- Question the "Leaked" Narrative. Real evidence of the supernatural wouldn't be hidden on a grainy TikTok with "spooky" music. It would be the biggest scientific discovery in human history.

- Check your biases. Are you seeing a face because it’s there, or because you’re looking for a reason to be afraid?

The most "real" images of the devil aren't found in a camera lens. They're found in the masterpieces of Bosch or the terrifyingly human portrayals of cinema. Those images matter because they reflect our own fears back at us. Everything else is just a glitch in the pixels.

Instead of hunting for a grainy photo, look into the "Codex Gigas"—the Devil’s Bible. It contains one of the most famous medieval portraits of the devil, supposedly drawn by a monk in a single night with the help of the prince of darkness himself. It’s a massive, beautiful, and deeply strange piece of history that offers a much more interesting "image" than any blurry doorbell cam ever will.