You’ve probably seen the photos. Maybe it was a viral Facebook post or a grainy thumbnail on a news site. Usually, it’s a literal island of trash—bottles, crates, and old tires so thick you could almost walk on them. It looks like a floating landfill in the middle of the ocean.

But here is the weird thing.

If you actually sailed out to the coordinates of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), you wouldn't see a giant mountain of rubbish peaking over the horizon. Honestly, you might sail right through the middle of it and not notice a thing. This is the biggest misconception fueled by images of the Pacific Garbage Patch that circulate online. People expect a continent. What they get is more like a thin, plastic soup.

It’s actually much scarier than a visible island.

The Viral Lie: Sorting Fact from Fiction

Most of the "popular" photos you see aren't even from the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. A very famous image often associated with the patch shows a diver swimming through a sea of thick debris, but that was actually taken in Manila Bay. Another shows a massive "island" of trash that turned out to be a harbor in the Caribbean after a storm.

We love the "island" narrative because it’s easy to understand. It’s a villain we can point at.

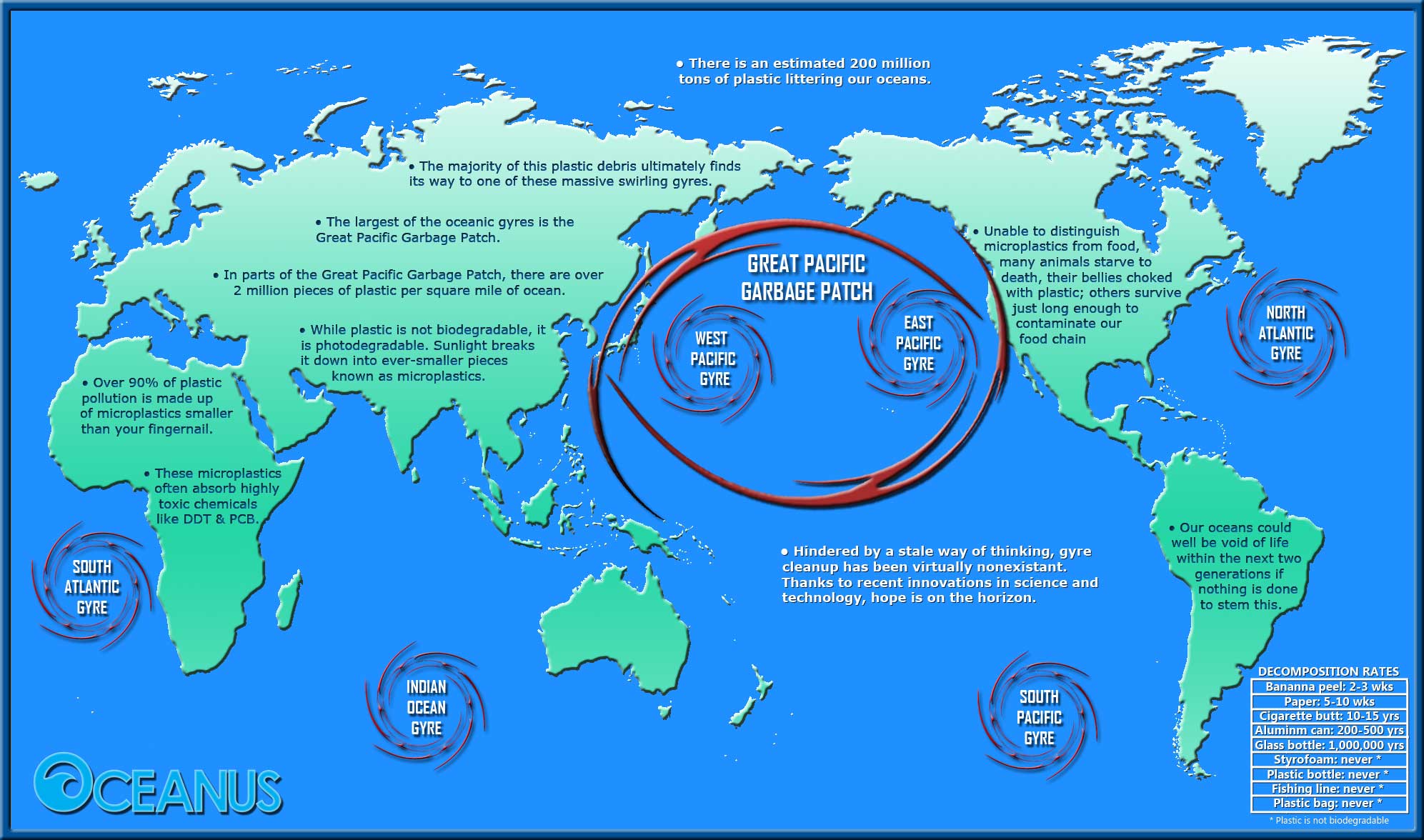

But the reality of the GPGP is a massive area—roughly twice the size of Texas or three times the size of France—where the water just looks a bit "cloudy." Capt. Charles Moore, who is widely credited with discovering the patch in 1997, described it not as a mountain of trash, but as a "plastic soup."

Think about that for a second.

If it were a solid island, we could probably just scoop it up with a crane. Because it’s a soup of microplastics, it’s integrated into the very ecosystem of the water column. It’s everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Why Real Images of the Pacific Garbage Patch Look "Empty"

If you look at verified photos from The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit founded by Boyan Slat, you’ll notice something different. You see vast stretches of blue water. Then, you see a ghost net. Or a single, sun-bleached laundry detergent bottle from the 1980s.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

The patch is a high-pressure area between Hawaii and California where rotating ocean currents (the gyre) pull debris inward. Once the trash is there, it’s trapped.

But the sun is a powerful force.

Photodegradation happens. The UV rays from the sun beat down on those floating milk jugs and fishing lines, making them brittle. Eventually, they don't disappear; they just shatter into trillions of tiny pieces called microplastics. Most of these are smaller than a grain of rice.

This is why satellite imagery can't "see" the patch. If you look at Google Earth, there’s no brown blob in the Pacific. The particles are too small and often sit just below the surface. To get an accurate "image" of what’s happening, scientists have to use neuston nets—fine-mesh nets that they drag behind boats. When they pull those nets up, that's when the horror becomes visible. It looks like colorful confetti mixed with plankton.

Actually, in some parts of the patch, there is more plastic by weight than there is biomass (living stuff). That’s a heavy thought.

The "Ghost" Problem

While microplastics make up the bulk of the particle count, the bulk of the weight in the patch comes from something else. "Ghost gear."

Research published in Scientific Reports indicates that about 46% of the mass in the GPGP is made up of fishing nets. These aren't just bits of string. They are massive, multi-ton tangles of polypropylene and nylon that have been lost or discarded by commercial fishing vessels.

When you see legitimate images of the Pacific Garbage Patch recovery efforts, you’ll see these massive, dripping heaps of green and black netting being hauled onto ship decks. These nets are "ghosts" because they keep fishing long after humans have touched them. They entangle sea turtles, choke seals, and crush coral reefs if they eventually drift into shallower waters.

It’s not just "us" throwing water bottles away—though that’s part of it. It’s a systemic industrial issue.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Complexity of the Water Column

We often focus on the surface because that's where the cameras are. But the GPGP isn't a 2D map. It’s 3D.

Microplastics have been found thousands of feet down. Some plastics are denser than seawater and sink immediately. Others get covered in algae and tiny barnacles (a process called biofouling) until they become heavy enough to drop to the seafloor.

So, while we talk about a "patch" on the surface, there is likely a "shadow" of trash on the ocean floor miles below. We have almost no photos of that. We are essentially looking at the tip of an iceberg, except the iceberg is made of HDPE and polystyrene.

The Survival of the "Plastic Island" Myth

Why does the media keep using fake photos? Honestly, it’s because the truth is boring to look at.

A photo of a clear blue ocean with a caption saying "This water contains 50,000 pieces of plastic per square kilometer" doesn't get clicks. A photo of a guy in a canoe in a literal river of trash gets clicks.

But this creates a dangerous "out of sight, out of mind" mentality. If people go to the beach and don't see a literal wall of garbage hitting the sand, they think the ocean is fine. They think the "patch" is some far-away problem that doesn't affect them.

The reality is that these microplastics are entering the food chain. Small fish eat the plastic "confetti" thinking it's plankton. Bigger fish eat the small fish. Then we eat the bigger fish. We are essentially eating our own trash, just filtered through a tuna first.

Can We Actually Clean It?

For a long time, the consensus was "no." It was too big, too far away, and the pieces were too small.

However, organizations like The Ocean Cleanup have developed long, floating barriers that act like an artificial coastline. These systems use the ocean's natural currents to concentrate the plastic into a "retention zone" where it can then be scooped up and taken back to land for recycling.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

They’ve already removed hundreds of thousands of kilograms.

But here is the catch.

Even if we cleaned up every single gram of plastic in the GPGP tomorrow, it would just fill back up. The problem isn't just the "patch" in the ocean; it’s the "leak" on land. Estimates suggest that millions of tons of plastic enter the ocean every year from rivers.

Cleaning the patch without stopping the flow is like trying to vacuum your house while someone is standing at the window throwing bags of dust inside. It’s a bit of a losing game unless you tackle both ends.

What You Can Do (Beyond Just Looking at Photos)

It's easy to feel paralyzed by the scale of this. You look at a photo of a dead albatross with a stomach full of plastic lighters and you want to give up. Don't.

The "images of the Pacific Garbage Patch" should be a catalyst, not a cause for despair.

Start by auditing your own life, but don't obsess over perfection. You've probably heard of "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle," but the most important one is "Refuse." Just say no to the stuff that’s designed to be used for five minutes and last for five hundred years.

Next Steps for Impact:

- Support Interceptor Technology: Look into groups that are placing "interceptors" in rivers. Stopping the plastic in the Citarum or the Yangtze is way more efficient than catching it once it hits the open Pacific.

- Question the "Island" Narrative: When you see a sensationalist photo, check the source. Educating others that the patch is a "soup" helps people understand why it’s a much more complex chemical and biological threat.

- Microplastic Awareness: Use laundry bags (like the Guppyfriend) that catch synthetic fibers from your clothes. Every time you wash a polyester fleece, thousands of microfibers go down the drain and, eventually, into the gyre.

- Demand Policy Change: Individual action is great, but global treaties on plastic production are better. Support legislation that holds manufacturers responsible for the entire lifecycle of their packaging.

The Pacific Garbage Patch isn't a place you can visit and stand on. It's a symptom of a global design flaw. We created a material that lasts forever and used it for things we throw away instantly. The "image" we should really be focused on isn't the trash in the water—it's the way we view our relationship with the things we buy.

The ocean is resilient, but it isn't a magic trash can. It's a living system that we are currently clogging up with the ghosts of our convenience. Turning the tide means changing the "soup" back into water, one less bottle at a time.