When you picture images of the god of war, your brain probably defaults to one of two things: a bearded guy in leather straps screaming at a Greek mountain, or a stoic statue in a dusty museum. Both are right. Both are also kind of misleading.

The way we "see" Ares or Mars—or even the modern reimagining of Kratos—is a messy tug-of-war between ancient propaganda and modern blockbuster aesthetics. If you look at a Greek vase from 500 BCE, Ares doesn't look like a superhero. He looks like a terrified soldier or a chaotic bully. Contrast that with the Roman Mars, who appears in sculpture as a dignified, muscular statesman. It’s a wild shift. Images are never just art; they’re a reflection of how a specific culture felt about the bloody business of combat.

The Brutal Evolution of Ares in Visual Media

Most people assume the Greeks loved Ares. They didn't. They feared him, and honestly, they kind of found him embarrassing. In early images of the god of war, Ares is often depicted with a spear and a helm, looking almost identical to any other hoplite soldier. There’s no "divine glow."

Take the Ludovisi Ares, a Roman copy of a Greek original. He’s sitting down. His sword is put away. He looks... bored? Pensive? This wasn't the "God of War" as a mindless killing machine. It was an image of the aftermath. The Greeks were obsessed with the psychological weight of war, not just the glory. When you see him on pottery, he’s often paired with Aphrodite, which was the ancient way of saying that even the most violent force in the universe is softened by desire.

Then you have the Roman transition. Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) was the big deal for Augustus Caesar. The Roman images of the god of war shifted toward the monumental. Huge marble statues. High-crested helmets. He became a symbol of the state's power rather than just a personification of bloodlust. If you’re looking at these images today, you have to ask: is he holding a shield to protect his people, or a sword to expand an empire? The answer usually depends on who paid for the statue.

From Marble to Pixels: The Kratos Effect

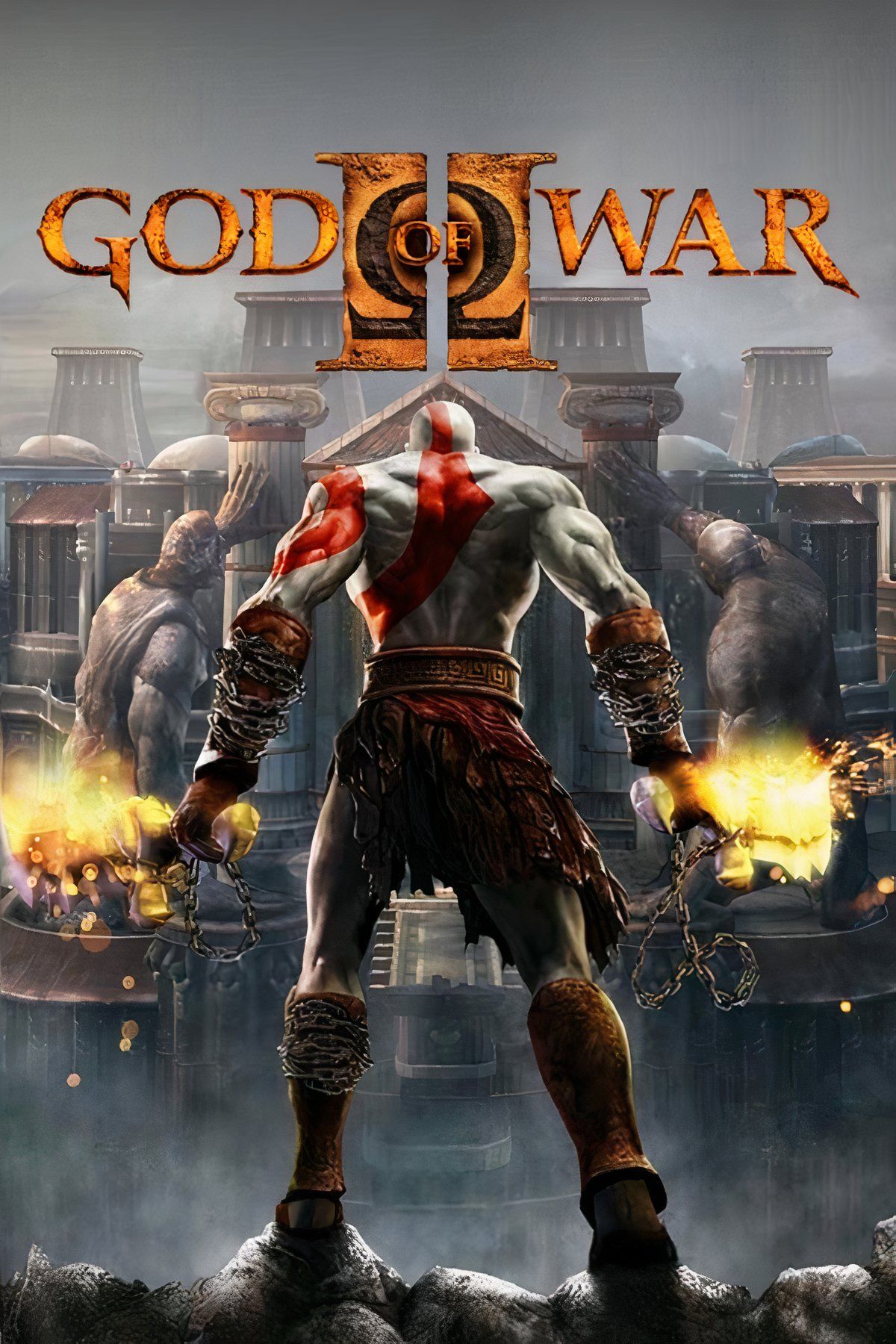

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. In the 21st century, images of the god of war are dominated by Santa Monica Studio’s Kratos. It is almost impossible to search for this topic without seeing a bald man with a red tattoo.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

This is where the imagery gets fascinating from a design perspective. Kratos isn't Ares. In the lore, he replaces Ares. But visually, he borrows from the "Berserker" archetype that is actually more Norse or Celtic than Greek. The ash-white skin—explained as the literal ashes of his family clinging to his body—is one of the most effective visual storytelling devices in gaming history. It takes the "image" of a god and turns it into a walking tombstone.

Think about the contrast in the 2018 and 2022 games. The images of the god of war changed from a lean, rage-filled youth to a "Dad Bod" deity. He’s wider. His beard is thick. His armor is fur-lined. This isn't just a graphics upgrade; it's a visual shift from war as "glory" to war as "burden." This mirrors the shift we saw from the Greek Ares to the Roman Mars, just in reverse. We went from a man who is war to a man who is trying to survive his own reputation.

Why We Are Obsessed With the Iconography of Violence

Visuals matter because war is hard to look at directly. We use images of the god of war as a proxy. Whether it's the Aztec Huitzilopochtli, often depicted as a hummingbird or a warrior with feathers, or the Hindu Kartikeya riding a peacock, these images try to make sense of destruction.

- The Armor: In almost every culture, the "God of War" is the most heavily accessorized. Why? Because armor represents the civilization's peak technology.

- The Eyes: Look closely at the eyes in ancient statues vs. modern CGI. Ancient statues often had blank or painted eyes to represent a detached, divine perspective. Modern images give Kratos or Mars "human" eyes full of regret.

- The Companions: Ares had Phobos (Fear) and Deimos (Terror). Mars had the wolf and the woodpecker. Modern imagery usually strips these away to focus on the "lone wolf" protagonist, which says a lot about our current obsession with individual heroism over collective military action.

Common Misconceptions in Modern Depictions

Let's clear some things up. If you see an image of the god of war wearing a Spartan plume that’s two feet tall, that’s mostly Hollywood. Real Corinthian helmets were practical.

Also, the "naked warrior" trope? That’s "Heroic Nudity." It was a Greek artistic convention to show off the perfect human form, not a suggestion that they went into battle without a tunic. If you see a digital painting of a god of war in a loincloth standing in the snow, that’s pure fantasy aesthetic. It looks cool on a 4K monitor, but it’s historically nonsensical.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Another big one: the color red. We associate Ares with red because of blood and the planet Mars. But in many ancient images of the god of war, the primary color was actually bronze or gold. Red became the "official" color of war much later, largely due to Roman military tunics and, eventually, modern color theory in cinema.

How to Analyze an Image of a War Deity

If you're a student of art history or just a fan of the genre, you should look for the "Attributes."

- The Weaponry: Is it a spear (distance/discipline) or a sword (closeness/savagery)?

- The Stance: Is he lunging forward or standing tall? A lunging god represents the chaos of the fray. A standing god represents victory and the "Pax Romana."

- The Scars: Modern images of the god of war use scars as a "resume" of past battles. Ancient images rarely did this; gods were supposed to be unblemished and eternal.

Honestly, the most "accurate" image of a war god is probably the one that makes you feel a little bit uneasy. It shouldn't just be "cool." It should be heavy. It should feel like something that could build a city or burn it down in the same afternoon.

Practical Steps for Sourcing and Using These Images

If you are looking for high-quality images of the god of war for a project, a blog, or even a tattoo, don't just hit Google Images and take the first thing you see.

First, check the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access collection. They have high-resolution, public-domain photos of actual Greek and Roman artifacts. You’ll find things there that look way more "metal" than anything a concept artist could dream up.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Second, if you’re looking at gaming assets, check out ArtStation. Look for "Key Art" from the God of War series or Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. This shows you the process of how a god is built—from the skeletal structure to the final shaders.

Third, understand the copyright. Most museum images of ancient statues are in the public domain, but photos of those statues taken by a specific photographer might not be. Always check the Creative Commons license.

To really understand the visual history, compare a 5th-century BCE bronze with a 19th-century Neoclassical painting and a 2024 game render. You’ll see the same man, but three completely different versions of what "power" looks like. One is a soldier, one is a hero, and one is a monster trying to be a man.

Start by visiting the digital archives of the British Museum and searching for "Ares." Look at the coins. Coins were the "social media" of the ancient world. How a king put a god of war on a coin tells you exactly how he wanted his enemies to see him: as a man with a very big god on his side.