Let’s be real for a second. Nobody wakes up and thinks, "I’d love to scroll through some high-definition photos of my large intestine today." It's just not on the bingo card. But when you’re sitting in a cold exam room and your gastroenterologist starts talking about images of the bowel, things get serious fast. Most people assume we’re just talking about a grainy screen during a colonoscopy. It's way more complex than that. We are talking about a massive, winding landscape inside your body that looks different depending on whether you’re looking through an endoscope, a CT scanner, or a tiny camera hidden inside a pill you swallowed.

The weird reality of looking inside yourself

The human gut is long. Really long. If you stretched it out, it would be about 25 feet of pink, pulsing tissue. Because of this, getting clear images of the bowel isn't as simple as taking a selfie. Different tools see different things. An MRI is great for the "outside-in" view, showing how the bowel sits among your other organs. But if you want to see the lining—the actual mucosa where things like polyps or inflammation hide—you need to get inside.

Ever heard of a "pill cam"? Technically, it's called capsule endoscopy. You swallow a device the size of a large vitamin, and it takes thousands of photos as it tumbles through your small intestine. This is a game-changer because traditional scopes usually can't reach the middle sections of the gut. It's like a tiny, lonely space probe traveling through a fleshy galaxy.

What do healthy images of the bowel even look like?

Honestly, a healthy bowel is kind of beautiful in a clinical way. It should look glistening and pink. Doctors look for a specific pattern of blood vessels, which usually looks like a fine, lacy network just beneath the surface. If that network is gone, or if the surface looks like wet sandpaper, that’s a red flag for inflammation.

When things go wrong, the pictures change dramatically. In cases of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the "landscape" looks angry. You might see deep ulcers that look like white craters or "cobblestoning," where the tissue swells up in lumps between cracks. Seeing these images of the bowel allows doctors to grade the severity of the disease without just guessing based on how much your stomach hurts. Pain is subjective; a 4K image of a bleeding ulcer is not.

💡 You might also like: Supplements Bad for Liver: Why Your Health Kick Might Be Backfiring

The role of "virtual" imaging

Not every look inside involves a tube. "Virtual colonoscopy" (CT Colonography) uses X-rays and fancy software to create a 3D fly-through of your gut. It’s less invasive, sure. But there’s a catch. If the radiologist sees a suspicious shadow on the digital scan, you still have to go in for a regular colonoscopy to get it snipped out. It’s a bit like seeing a potential leak on a satellite map of your house; eventually, someone has to go in with a wrench.

Radiologists like Dr. Perry Pickhardt at the University of Wisconsin have pioneered how we use these digital images of the bowel to catch cancer early. The tech is so good now that it can spot polyps smaller than a pea. But the prep—the part where you drink that gallon of salty liquid—is unfortunately still required. You can't see the "wall" if the "room" is full of... well, you know.

Why high-resolution matters for cancer screening

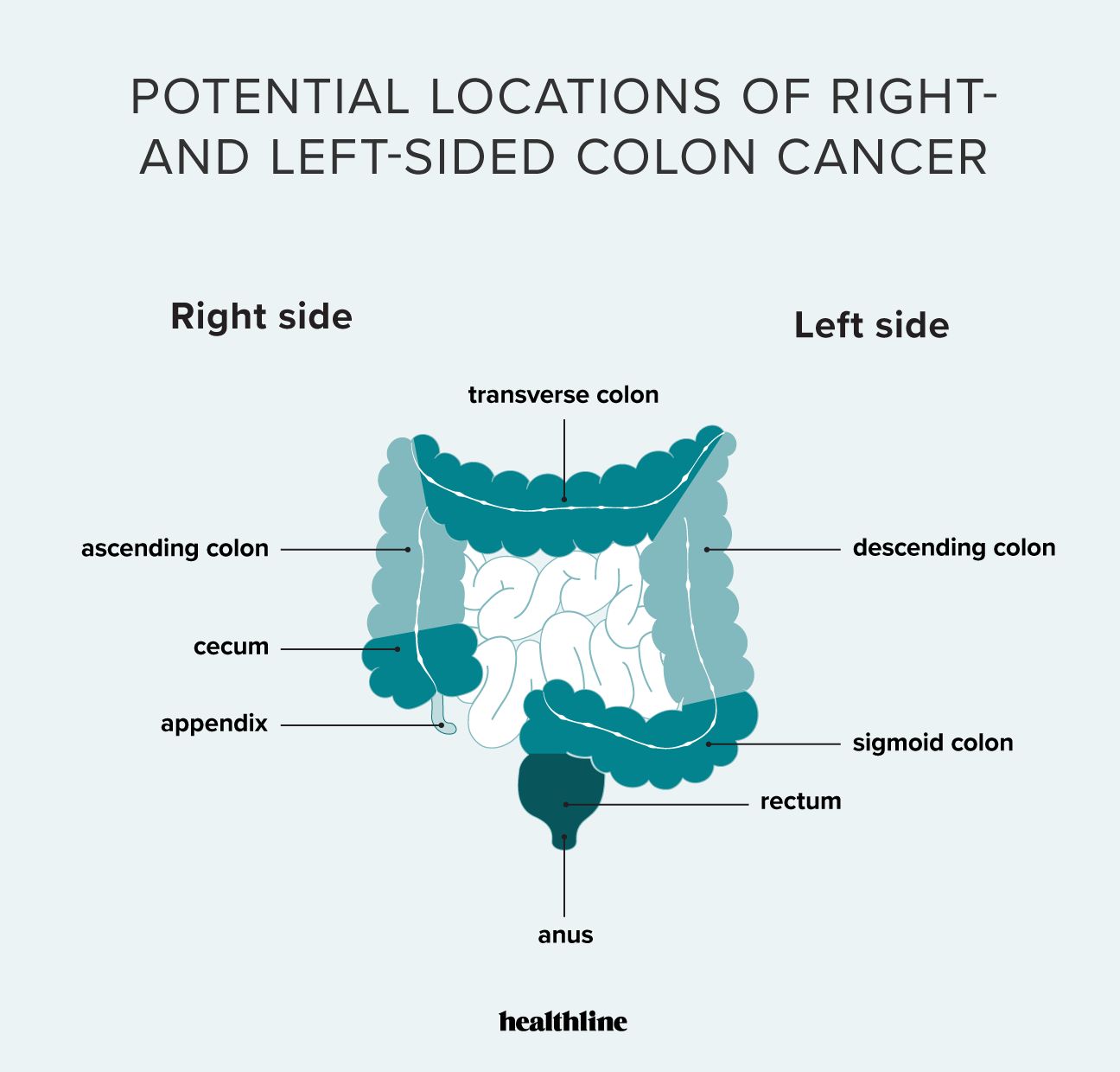

Colon cancer is one of the most preventable cancers because it usually starts as a polyp. A polyp is basically a tiny mushroom growing on the wall of your gut. If a doctor sees it on one of these images of the bowel, they can literally reach out with a wire loop and zapping tool to remove it right then and there.

We’ve moved past the days of blurry black-and-white feeds. Modern scopes use NBI—Narrow Band Imaging. This is a special light filter that highlights the blood vessels in polyps. Since tumors need lots of blood to grow, they "glow" darker under this light. It’s like turning on a blacklight in a dark room to find a neon sign. This technology has significantly boosted the "adenoma detection rate," which is just a fancy way of saying doctors are getting much better at finding the bad stuff before it turns into a nightmare.

📖 Related: Sudafed PE and the Brand Name for Phenylephrine: Why the Name Matters More Than Ever

Misconceptions about what you'll see

People often freak out thinking their gut is going to look "dirty." It won't. If you did the prep right, it looks like the inside of a clean, wet balloon. Another weird thing? The bowel actually moves. It’s not a static pipe. It’s constantly squeezing and shifting (peristalsis). When a doctor is capturing images of the bowel, they often have to puff a little air or CO2 inside to keep the walls from collapsing so they can see around the corners.

There's also the "red herring" problem. Sometimes, someone sees a red spot on a scan and panics. But it might just be an "angiodysplasia"—a harmless, tiny malformed blood vessel that looks like a spider web. Not every spot is a tumor. Not every shadow is a crisis. Context is everything in gastroenterology.

The future: AI is watching your gut too

This sounds like sci-fi, but AI is already integrated into many endoscopy suites. As the doctor moves the camera, an AI overlay runs in real-time, placing little green boxes around things it thinks are polyps. It’s like a second pair of eyes that never gets tired or distracted. These AI-driven images of the bowel are helping less experienced doctors perform at the level of veterans.

Studies, like those published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, show that AI assistance can increase the detection of precancerous polyps by over 10%. That’s thousands of lives saved just by having an algorithm double-check the "video feed" of a human's insides.

👉 See also: Silicone Tape for Skin: Why It Actually Works for Scars (and When It Doesn't)

Practical steps if you're facing an imaging procedure

If your doctor has ordered any kind of scan or scope to get images of the bowel, don't just show up and hope for the best. The quality of the "photo" depends almost entirely on you.

- Take the prep seriously. If the bowel isn't empty, the images are useless. It’s like trying to take a photo of a floor through a pile of laundry.

- Ask about the technology. Is your doctor using High-Definition scopes? Do they use NBI or other "image enhancement" tools?

- Request the photos. You have a right to your medical records. Seeing the images yourself can help you understand your diagnosis, whether it's Diverticulosis (tiny pouches in the wall) or Colitis.

- Check the "viewing" window. If you’re getting a CT or MRI, ask if it’s a "weighted" scan specifically for the bowel (like an MRE), which uses a special contrast drink to distend the small intestine for better clarity.

Understanding what is happening when doctors look at images of the bowel takes the mystery out of the process. It's not just "pictures"; it's a map of your internal health. Whether it's a routine screen or investigating a mystery pain, these visuals are the most powerful tool we have to stop problems before they start.

Next Steps for Your Health

If you have a family history of colon issues or you're over 45, talk to your GP about which imaging method is right for you. Don't wait for symptoms like bleeding or "pencil-thin" stools; at that point, the images usually show something much harder to treat. The goal is to find nothing. A "boring" image of a pink, healthy bowel is the best result you can ever get.