You’ve probably seen the "bees around a hive" picture. It’s that famous graphic of Earth completely smothered in a thick, glowing cloud of white dots. It looks terrifying. It looks like we’re trapped in a cage of our own making. But honestly? That’s not a photograph. It’s a visualization, and while it’s based on real data from agencies like ESA (European Space Agency), it’s fundamentally misleading if you take it literally. If those dots were actually the size they appear to be in the graphic, each piece of junk would be the size of Paris.

Space is big. Really big.

When people go looking for images of space debris, they’re usually looking for proof of the "Kessler Syndrome"—that nightmare scenario where one collision starts a chain reaction that shreds every satellite we own. We want to see the wreckage. We want the "Star Wars" graveyard of twisted metal floating over the horizon. The reality of what we can actually photograph from the ground or from other satellites is much more haunting, much more technical, and arguably way more dangerous than a CGI render suggests.

The struggle to capture real images of space debris

Why don't we have more high-resolution, "National Geographic" style photos of the junk up there? Physics is a bit of a jerk about it.

Most space debris is moving at about 17,500 miles per hour. That is roughly seven times faster than a bullet. If you’re trying to snap a selfie with a piece of a spent Russian rocket stage as it zooms past your satellite, you’re going to get a blur, if you get anything at all. Most of the images of space debris that look like "real" photos are actually sensor data reconstructions or incredibly high-end radar imagery.

Take the work of HUSIR, the Haystack Ultra-wideband Satellite Imaging Radar. MIT Lincoln Laboratory uses this massive dish to "see" objects in orbit. The images it produces aren't what your eyes see; they are radar returns that show the shape and orientation of the object. They look like ghostly, pixelated versions of satellites. In 2023, the world got a rare look at the upper stage of an H-IIA rocket through the eyes of Astroscale’s ADRAS-J mission. That was a big deal. It was a "proximity rendezvous," meaning a chaser satellite got close enough to actually take a recognizable photo of a piece of space junk from just a few meters away.

It looked lonely. And surprisingly intact.

💡 You might also like: Examples of an Apple ID: What Most People Get Wrong

The "White Dot" problem in visualizations

We have to talk about those CGI models again because they dominate Google Images. NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office uses these to track the roughly 35,000 objects larger than 10 centimeters currently being monitored. But there are millions of smaller pieces—paint flakes, frozen coolant from old Soviet RORSAT satellites, and bits of exploded bolts.

If you tried to make an accurate map where the dots were to scale, the dots would be invisible. You wouldn't see a "cloud." You'd see a big blue marble and nothing else. The reason artists make the dots huge is to show the density and the risk, not the physical appearance. This creates a weird disconnect where the public thinks we’re literally flying through a junkyard, while astronauts on the ISS often look out the window and see... nothing. Just the blackness of the void.

Until something hits the window.

When the debris hits back: Real photos of damage

If you want to see the most honest images of space debris, you shouldn't look at the sky. You should look at the stuff that came back down. Or the stuff currently occupied by humans.

- The ISS Cupola Window: In 2016, Tim Peake snapped a photo of a 7mm chip in one of the International Space Station’s windows. What caused it? A tiny flake of paint or a small metal fragment, probably no more than a few thousandths of a millimeter across. At orbital speeds, that flake has the energy of a dropped bowling ball.

- The Endeavour Shuttle Tail: There is a famous photo of a hole in the radiator of the Space Shuttle Endeavour (STS-118). It looks like a clean gunshot wound.

- Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF): This was a giant school-bus-sized experiment NASA left in orbit for nearly six years. When they finally brought it back in 1990, it was covered in over 20,000 tiny craters.

These are the "real" images. They aren't sweeping vistas of wreckage; they are clinical, terrifying close-ups of what happens when kinetic energy meets aluminum and glass. It's the difference between seeing a map of a minefield and seeing a boot that stepped on one.

Tracking the "Unseen" 100 million

Statistically, the things we can't photograph are the things that will end our modern way of life. There are an estimated 130 million pieces of debris between 1mm and 1cm. We can’t track them. We can’t photograph them. We can only "see" them when they impact a solar panel and cause a satellite to go dark.

📖 Related: AR-15: What Most People Get Wrong About What AR Stands For

Professor Don Kessler, the man who gave the "Kessler Syndrome" its name, once noted that the problem isn't the big stuff we see in images of space debris—it's the grinding down of that big stuff into a lethal dust. Think of it like a car crash. The initial impact is bad, but the glass shattering into a million pieces and flying into your face is what does the secondary damage.

Is the situation actually getting worse?

Actually, yes. It's getting much worse, and the images from the last five years prove it.

The launch of mega-constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink has fundamentally changed the "look" of our orbit. If you’ve ever seen a "Starlink Train" photo—those long strings of bright lights moving across the night sky—you’re looking at the new face of orbital congestion. While Starlink satellites aren't "debris" (they are active and maneuverable), they add to the total mass in orbit.

When things go wrong, they go wrong spectacularly. In 2021, a Russian Anti-Satellite (ASAT) test created a massive cloud of debris that forced the ISS crew to take shelter in their return capsules. The radar tracks from that event looked like a literal explosion frozen in time. Those tracks are the most accurate "images" we have of a fresh debris field. They show a localized cluster that slowly spreads out over months into a "shell" around the entire planet.

The legal and political nightmare

Who owns the junk? That’s the catch. Under the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, a country is responsible for its space objects forever. You can’t just go up and "clean up" a piece of a Chinese rocket or a Russian spy satellite without permission. That would be considered an act of war or theft.

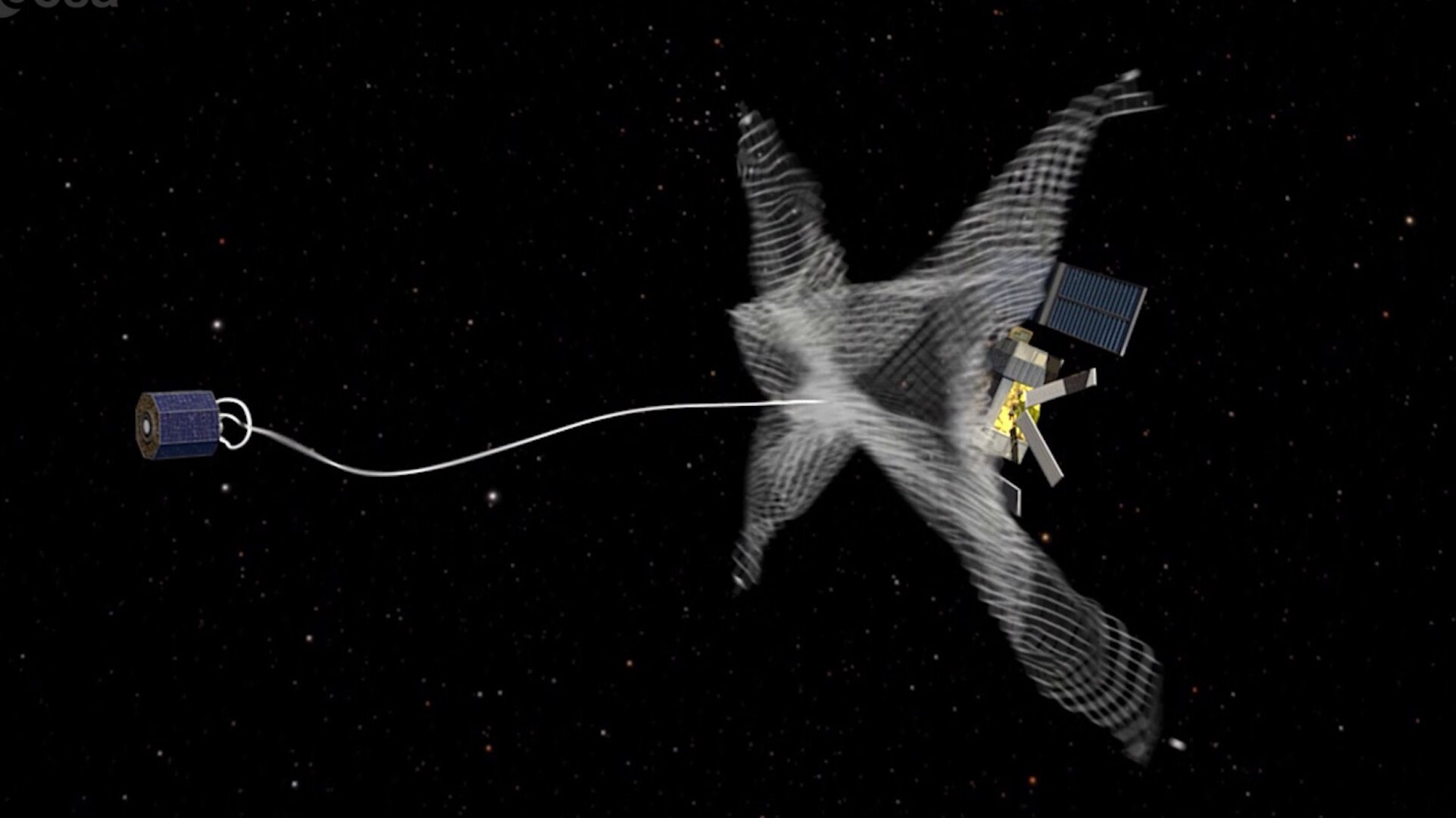

This is why we don't have many close-up images of space debris from "janitor" satellites. We are only just now beginning to test the technology to even get near these objects. Japan’s Astroscale and the European Space Agency’s ClearSpace-1 mission are the pioneers here. ClearSpace-1, scheduled for 2026, aims to capture a Vespa adapter (a piece of rocket hardware) using a giant robotic claw.

👉 See also: Apple DMA EU News Today: Why the New 2026 Fees Are Changing Everything

Imagine the photos we'll get from that. It will be the first time humanity actually "touches" its trash in deep space.

How to spot a fake space debris photo

If you're browsing the web and see a photo of space debris, look for these red flags to tell if it's real or a render:

- The Lighting: If the debris is perfectly lit from all sides, it’s a render. In space, lighting is harsh. One side is blindingly bright from the sun, and the other is pitch black.

- The Earth’s Curve: If the Earth looks like a perfect, vibrant blue marble in the background with hundreds of distinct, sharp "satellite" shapes visible, it’s a visualization. To see the Earth that way, you have to be thousands of miles away. At that distance, satellites are too small to see.

- The Motion: Real photos from orbit often have a slight "streak" or a very shallow depth of field.

- The Source: Real images usually come from NASA, ESA, JAXA, or specialized companies like LeoLabs (which produces amazing radar visualizations that look like neon maps).

What we can do right now

We are at a tipping point. The "Tragedy of the Commons" is playing out 300 miles above our heads. If we don't start cleaning up the big stuff—the abandoned rocket bodies that act as ticking time bombs—we won't be able to use certain orbits at all.

Actionable Insights for the Space-Conscious:

- Support "Space Sustainability" Ratings: Some organizations are pushing for a rating system for satellite operators, similar to LEED certification for buildings. Support companies that commit to de-orbiting their satellites within five years of mission end.

- Follow Real-Time Tracking: Use tools like "Stuff in Space" or "See A Satellite Tonight." These sites use real NORAD data to show you exactly where the junk is. It's much more sobering than a fake CGI image.

- Demand Policy Change: The FCC in the US recently started fining companies for failing to de-orbit their satellites. This is a massive step. It turns "trash" into a financial liability.

- Look Up: Get a pair of binoculars. On a clear night, just after sunset, look up. Those moving "stars" aren't all planes. Many are the very objects you see in those images of space debris. Seeing it with your own eyes changes your perspective on how crowded our "empty" sky really is.

The next decade will determine if our orbit stays a gateway to the stars or becomes a graveyard that keeps us grounded. The images we capture in the next few years—the real ones, the gritty, radar-mapped, claw-grabbing ones—will tell the story of whether we learned to clean up after ourselves or not.

Practical Next Steps:

- Visit the ESA Space Debris Office website to view their annual Space Environment Report. It contains the most factually accurate, non-sensationalized data charts available.

- Check out LeoLabs' visualizations for a look at how commercial radar tracks thousands of objects in real-time. This is the closest you can get to seeing the "live" state of orbital junk.

- Search for "ADRAS-J mission photos" to see the most recent, high-resolution actual photographs of an uncooperative piece of space debris in Earth orbit.