Scorpions are basically the stuff of nightmares for anyone living in the Southwest or tropical climates. You're walking through the garage in flip-flops, or maybe reaching for a gardening glove, and suddenly—bam. It feels like a cigarette burn or a sharp electric shock. Then you’re on Google, frantically typing in images of scorpion stings to see if that tiny red dot on your thumb is going to kill you or just ruin your weekend.

Honestly? Most of the time, the "image" isn't even that impressive.

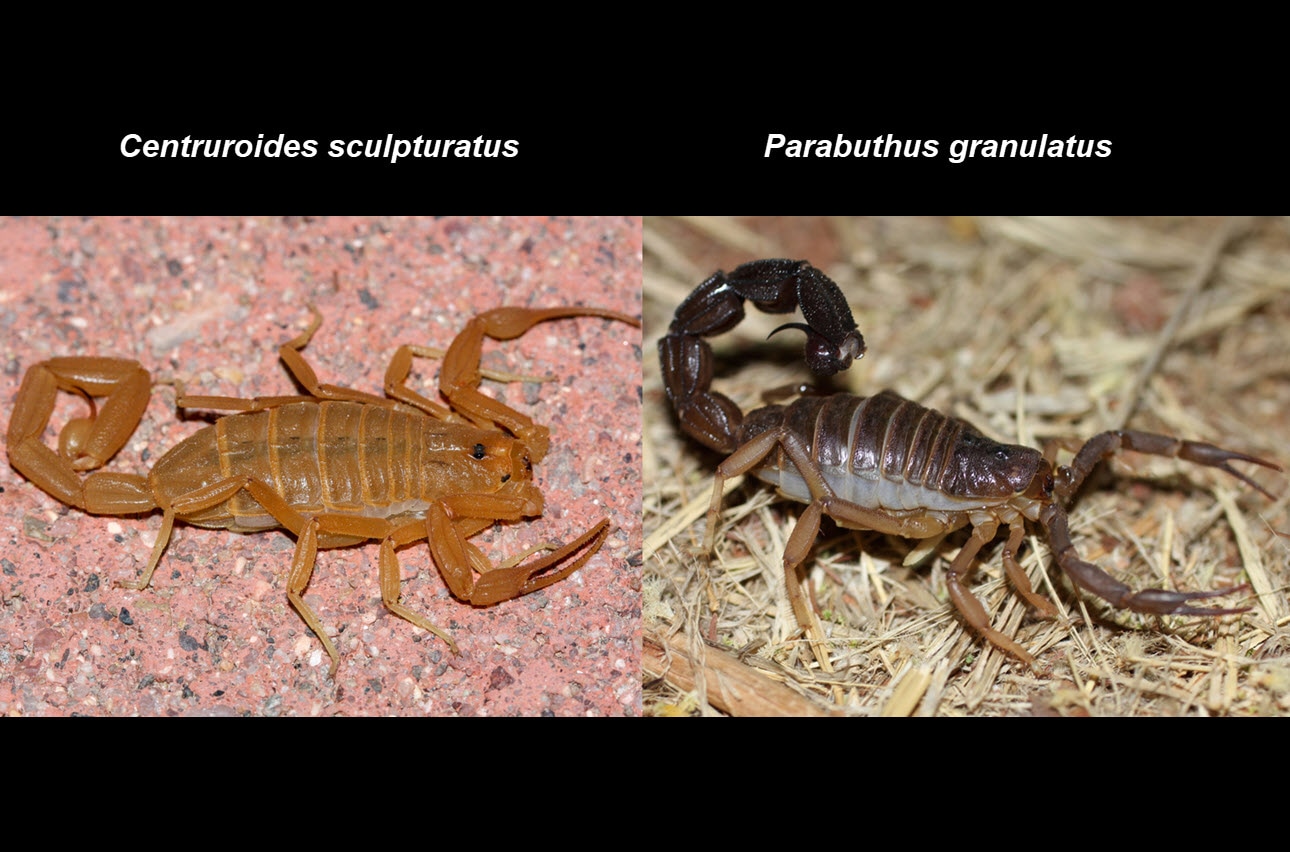

If you’re looking at your skin right now and seeing a massive, weeping sore or a giant purple welt, you might actually be looking at a spider bite or a skin infection. Scorpion stings are deceptive. Most species, including the infamous Arizona Bark Scorpion (Centruroides sculpturatus), leave almost no local mark. You might see a tiny puncture, some mild swelling, or a bit of redness. It’s the stuff happening under the skin that matters.

Identifying the Mark: Why Images of Scorpion Stings Can Be Misleading

The problem with searching for a visual reference is that everyone reacts differently. I’ve seen people get stung by a Striped Bark Scorpion and look like they were hit by a bee—swollen, red, itchy. Then you have the Bark Scorpion stings where the skin looks completely normal, yet the person is in absolute agony.

It's weird.

If you look at medical databases like those maintained by Banner Health or the University of Arizona’s Poison and Drug Information Center, they’ll tell you that the lack of a "gross" wound is actually a hallmark of a scorpion sting. Unlike a Brown Recluse bite, which causes necrotic skin death (basically a hole in your arm), a scorpion’s venom is neurotoxic. It targets your nerves, not your flesh.

What You’ll Likely See

- A small red puncture: This is the "hit" site. It’s usually no bigger than a pinprick.

- Mild edema: That’s just fancy doctor-speak for slight swelling.

- No discoloration: In about 80% of cases, there is zero bruising or darkening of the skin initially.

I remember talking to a paramedic in Phoenix who said the most common mistake people make is waiting for the sting site to "look bad" before calling for help. If you wait for the skin to turn colors, you're looking for a symptom that might never come, even if you’re heading toward systemic toxicity.

The Bark Scorpion Factor

We have to talk about the Bark Scorpion because it’s the heavy hitter in North America. If you find images of scorpion stings from this specific critter, you’ll notice they look identical to a harmless sting from a common desert hairy scorpion. But the symptoms are worlds apart.

🔗 Read more: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

The Bark Scorpion is small, yellowish-tan, and can climb walls. It doesn't need to be big to be scary. When it stings, the venom moves through the bloodstream and starts "misfiring" your nerves.

Have you ever had your foot fall asleep and get that "pins and needles" feeling? Imagine that, but cranked up to ten and spreading across your whole body. This is called paresthesia. It’s the primary way doctors diagnose a serious sting when the visual evidence on the skin is lacking.

When the Image Becomes a Medical Emergency

Most healthy adults handle scorpions just fine. It’s like a really bad wasp sting. You ice it, you take some ibuprofen, you swear a lot, and you move on. But for kids and the elderly, it’s a whole different game.

Grades of Envenomation

Medical professionals actually categorize these stings into grades.

- Grade I: Local pain and some tingling. The skin looks fine.

- Grade II: Pain and tingling that starts to travel. If you got stung on the finger, your elbow starts hurting.

- Grade III: This is the danger zone. Cranial nerve dysfunction. You might see the person’s eyes jerking around (nystagmus) or they might start drooling because they can’t swallow properly.

- Grade IV: Total loss of muscle control, foaming at the mouth, and potential respiratory failure.

At Grade III and IV, the "image" of the sting is the last thing anyone is looking at. They’re looking at the patient’s face. The Anascorp antivenom, which was FDA approved back in 2011, is a literal lifesaver here, but it’s incredibly expensive—sometimes costing thousands per vial.

Distinguishing Stings from Other Bites

You might think you’ve been stung, but the visual evidence suggests otherwise.

Spiders vs. Scorpions

A Black Widow bite often shows two distinct puncture marks. A Brown Recluse bite eventually develops a "bullseye" pattern with a dark center. Scorpion stings? Just one singular, barely visible point.

💡 You might also like: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

Bee Stings

A honeybee leaves a stinger behind. Scorpions don't. If there’s a barb stuck in your skin, it wasn’t a scorpion. Also, bee stings tend to swell much more aggressively in the first ten minutes than a scorpion sting does.

Allergic Reactions

This is the wild card. Some people are allergic to scorpion venom the same way people are allergic to peanuts. In this case, the images of scorpion stings will show hives, massive swelling, and the person might struggle to breathe (anaphylaxis). This is different from the neurotoxic reaction. This is an immune system meltdown.

Real-World Treatment: Forget the Movies

Please, for the love of everything, do not try to "suck out the venom."

I’ve seen people try to use those "extractor" pumps you see in camping stores. They don't work. By the time you’ve grabbed the kit, the venom has already entered the capillary system. You’re just bruising your skin and making it harder for a doctor to see what's actually happening.

Also, don't use a tourniquet. You aren't in a 1950s Western. Cutting off blood flow can actually cause more localized tissue damage because you’re concentrating the venom in one small area rather than letting the body’s natural systems dilute it.

The Simple Protocol

- Wash it: Use soap and water. Simple.

- Cool it: Use a cold compress. Not ice directly on the skin—that can cause frostbite—but a cold, damp cloth.

- Elevate it: Keep the sting site at heart level.

- Monitor: Watch for the "tapping test." If you tap the sting site and it sends a jolt of "electricity" through the limb, that’s a sign of a neurotoxic sting.

The "Scorpion Season" Myth

People think scorpions only come out in the heat of August. While they are more active when it’s warm, they love a good monsoon. Rain drives them inside. In Arizona and Nevada, "Scorpion Season" is basically whenever the temperature is above 70 degrees.

I’ve heard stories of people finding them in their shoes in the middle of November because the scorpion was looking for a warm place to hide. Always shake out your boots. Always.

📖 Related: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

If you’re trying to find scorpions before they find you, buy a UV flashlight (blacklight). Most scorpions fluoresce a bright, eerie green under UV light. It’s actually pretty cool to see, provided they aren't in your bed. This happens because of a protein in their exoskeleton. Interestingly, even fossilized scorpions from millions of years ago still glow under blacklight.

Actionable Steps for Management

If you or someone else has been stung, stop scrolling through images of scorpion stings and follow these steps immediately.

First, take a deep breath. Unless it’s a small child or an infant, the odds are very high that you will be completely fine. Call your local poison control center. In the U.S., that’s 1-800-222-1222. They are experts and can walk you through the symptoms better than a search engine can.

Second, if the victim is a child, get to an emergency room. Children have less body mass, meaning the venom concentration is much higher for them. Don't wait for "Grade III" symptoms like weird eye movements.

Third, try to (safely) identify the scorpion. If it’s dead, put it in a jar. If it’s alive, take a quick photo with your phone if you can do it without getting close. Knowing if it was a Bark Scorpion versus a Giant Desert Hairy Scorpion helps the medical team decide if antivenom is necessary.

Finally, manage the pain. It’s going to hurt for about 24 to 72 hours. It’s a lingering, throbbing, annoying pain. Use acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Avoid narcotics, as they can sometimes suppress breathing, which is a risk if the venom also starts affecting the respiratory system. Keep the area clean and don't poke at it. Most people recover fully with nothing more than a localized "zing" that fades over a few days.