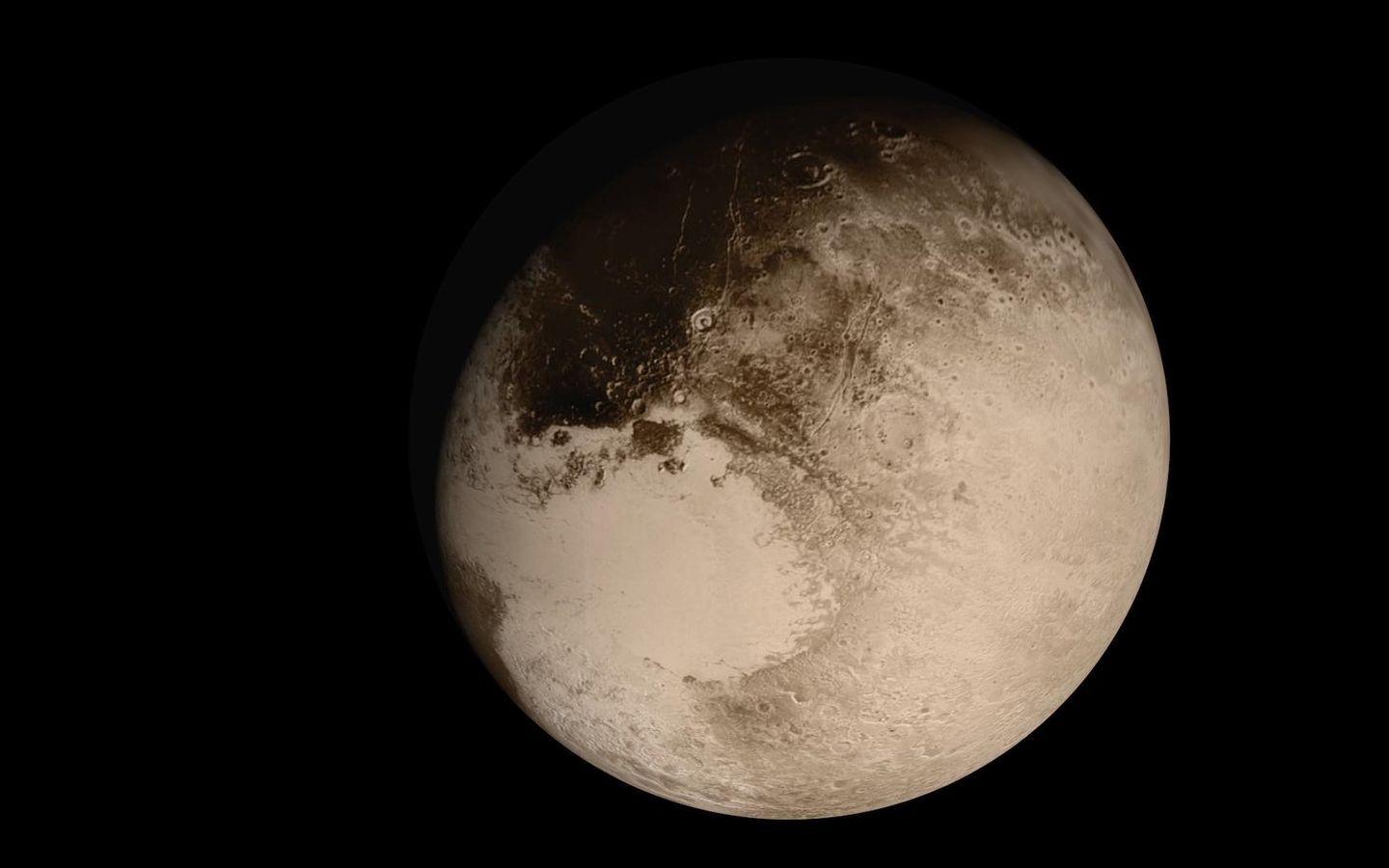

For decades, we saw a smudge. A blurry, pixelated, gray-beige marble that looked more like a dirty ping-pong ball than a world. Then 2015 happened. When the New Horizons spacecraft screamed past the Kuiper Belt at 36,000 miles per hour, our collective screens were flooded with high-resolution images of Pluto NASA released to a stunned public. It wasn't gray. It wasn't boring. It had a giant, icy heart.

But here’s the thing: most of the vibrant, psychedelic photos you see on social media aren't what you'd see if you were looking out a porthole.

Pluto is a weirdo. It’s a complex, geologically active powerhouse that basically spat in the face of everyone who thought small, cold rocks were "dead." Understanding the photography behind this mission isn't just about looking at pretty pictures; it’s about how NASA engineers use "false color" to see things the human eye is literally too weak to perceive.

📖 Related: Apple Genius Bar Appointments: How to Actually Get Help Without Losing Your Mind

The Giant Heart and the Red Snow

The most famous feature in the images of Pluto NASA captured is officially named Tombaugh Regio. Most of us just call it the "Heart." This isn't just a random shape. It’s a massive glacier made of nitrogen ice.

NASA’s Ralph instrument—a combination of a visible light camera (MVIC) and an infrared spectrometer (LEISA)—is responsible for the data that builds these shots. When you see a version of Pluto that looks bright red or deep purple, you’re looking at a compositional map. The reds often represent "tholins." These are complex organic molecules that form when methane and nitrogen are hit by cosmic rays. Think of it as a cosmic sunburn. It’s basically organic soot that rains down and stains the surface.

The variety is staggering. One minute you’re looking at the "Sputnik Planitia," which is as smooth as a skating rink because it’s a churning convection cell of nitrogen. The next, you’re looking at the "Bladed Terrain" of Tartarus Dorsa. These are giant shards of methane ice, some as tall as skyscrapers. Why do they exist? Sublimation. The ice goes straight from solid to gas, carving out wicked, jagged edges that look like something out of a sci-fi horror flick.

Why the Colors Look So "Fake"

Let's get real about the "true color" debate. If you were standing on Pluto at high noon, it would feel like twilight on Earth. The sun is just a very bright star. Because of this, NASA often boosts the saturation in released images.

They do this to highlight the "chemical provinces." If everything were rendered in the muted, brownish-gray that the human eye would actually see, we’d miss the fact that the "Heart" is chemically distinct from the dark, cratered Cthulhu Macula (yes, NASA nerds named a region after Lovecraft).

The Blue Haze Mystery

One of the most breathtaking images of Pluto NASA sent back shows a blue ring around the planet’s silhouette. It looks like Earth’s atmosphere. It’s beautiful.

But it’s an illusion of physics.

The particles in Pluto’s haze are likely gray or red, but they are so small that they scatter blue light—the same phenomenon, known as Rayleigh scattering, that makes our sky blue. When New Horizons looked back at the sun through Pluto’s atmosphere, it caught this blue glow. It proved that Pluto has a layered, structured atmosphere that extends hundreds of miles into space. It’s thin, sure, but it’s there, and it’s surprisingly complex.

The Complexity of the Five Moons

Pluto isn't alone. It’s part of a binary system, really. Its largest moon, Charon, is so big that the two of them actually orbit a point in empty space between them.

When we got the first high-res shots of Charon, scientists expected a cratered, dead moon. Instead, they found Mordor Macula. That’s the "Red Spot" at Charon’s north pole. It turns out Pluto is "spraying" its atmosphere into space, and Charon is catching some of it. The methane from Pluto gets trapped at Charon’s poles, freezes, and gets baked by UV light into that same red tholin "gunk" we see on the parent planet.

The other four moons—Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra—are basically chaotic tumbling potatoes. Because Pluto and Charon create such a wobbly gravitational field, these smaller moons don't have a "dark side." They spin wildly. Imagine trying to set a clock on a moon where the sun rises in the north one day and the west the next.

🔗 Read more: Why a 40 inch monitor curved setup is actually the sweet spot for productivity

Data is Not an Instant Download

People often forget how hard it was to get these images of Pluto NASA published. New Horizons was about 3 billion miles away. The data transfer rate was roughly 1 to 2 kilobits per second. To put that in perspective, a single high-res photo took hours to transmit.

It took over 15 months to get all the data from that one flyby back to Earth.

Scientists like Alan Stern, the Principal Investigator for the mission, had to wait in agonizing silence as the bits trickled in. Each new image debunked a previous theory. We thought Pluto would be a battered, cratered rock like our Moon. Instead, we saw mountains made of water ice that are as tall as the Rockies. We saw signs of a subsurface ocean that might still be liquid today, kept warm by radioactive decay in the core and the insulating "blanket" of nitrogen ice on top.

How to View Pluto Images Like a Pro

If you want to dive into the raw files, don't just look at Pinterest. Go to the PDS (Planetary Data System) or the New Horizons mission gallery hosted by Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

- Look for the LORRI images: These are Long Range Reconnaissance Imager shots. They are black and white but have the highest spatial resolution. They show the "cracks" and "pits" in the ice.

- Check the MVIC overlays: These provide the color. When you see a "natural color" image, it’s a best-guess reconstruction using the Red, Blue, and Near-infrared filters.

- Search for "Pluto at Night": These are the backlit images showing the haze layers. They are the most technically difficult to capture because the camera has to avoid being blinded by the sun.

What’s Next for the King of the Kuiper Belt?

There are no current missions going back to Pluto. It’s a tragedy of funding and physics. To orbit Pluto, rather than just fly by, a spacecraft would need an enormous amount of fuel or a massive nuclear engine to slow down.

However, the data we already have is being re-processed with 2026-era AI and deconvolution algorithms. We are seeing sharper details in the old 2015 photos than we did ten years ago. We’re finding "cryovolcanoes"—ice volcanoes—like Wright Mons, which may have been erupting "lava" made of slushy ice in the recent geological past.

To truly appreciate the images of Pluto NASA provides, you have to look past the "Planet or Not" debate. Whether it’s a planet, a dwarf planet, or a giant ice ball doesn't matter to the geology. The images show a world that is alive, changing, and deeply weird.

✨ Don't miss: Beolab 90: What Most People Get Wrong About These 8,200-Watt Giants

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts

- Visit the NASA Photojournal: Search specifically for "PIA19952" to see the highest-resolution global map ever created.

- Use NASA's Eyes: Download the "NASA's Eyes on the Solar System" app. It allows you to simulate the New Horizons flyby in real-time 3D, showing exactly where the cameras were pointed when specific famous shots were taken.

- Check the Raw Feeds: Follow the New Horizons mission page for occasional updates as they continue to study the Kuiper Belt Object "Arrokoth," which the probe visited after Pluto.

- Adjust Your Monitor: To see the subtle gradients in the "dark" regions of Pluto (like Cthulhu Macula), ensure your display's black levels are calibrated; otherwise, the most interesting organic chemistry looks like a flat black blob.

The legacy of these images is a shift in perspective. We used to think the outer solar system was a graveyard. Now we know it’s a frontier.