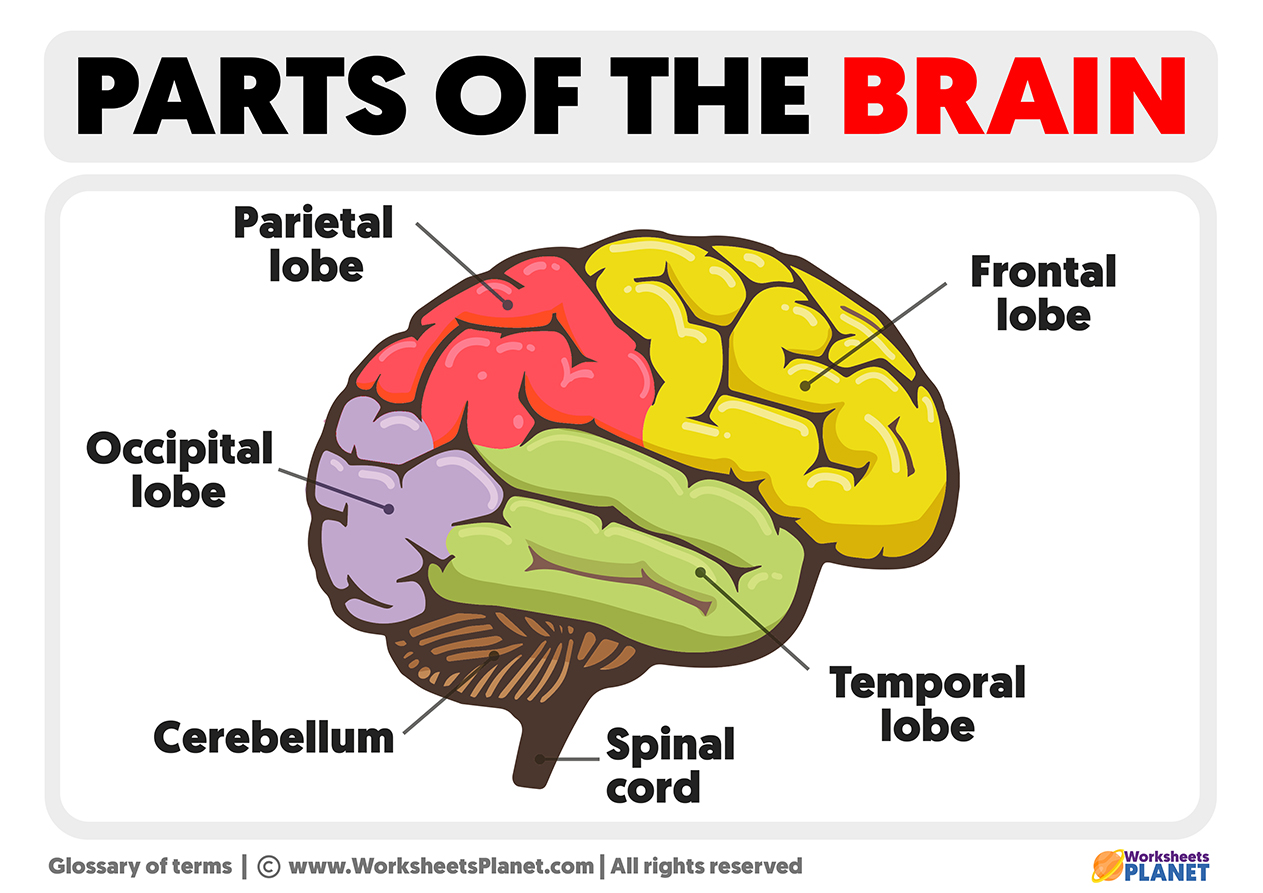

You've seen them. Those neon-colored, perfectly mapped-out images of parts of the brain that make it look like your head is a neatly organized filing cabinet. The frontal lobe is blue. The temporal lobe is yellow. Everything has a nice, clean border.

It's a lie. Well, a half-truth at best.

The reality of neuroanatomy is messy. If you actually looked at a human brain on an operating table, you wouldn't see colors. You’d see a grayish-pink slab of tissue that looks remarkably like firm tofu or a large walnut. The distinct "parts" we talk about aren't separate rooms; they are overlapping functional zones. Understanding how we visualize these areas is the difference between passing a high school biology quiz and actually grasping how your consciousness functions.

The Problem with Traditional Brain Mapping

Most people think of the brain like a map of the United States. New York ends exactly where New Jersey begins. But the brain is more like the ocean. Where does the Atlantic end and the Caribbean start? It’s all water.

Take the "Limbic System." You’ll find thousands of images of parts of the brain highlighting the amygdala and hippocampus as this discrete "emotional center." However, many modern neuroscientists, like Lisa Feldman Barrett, argue that the limbic system isn't even a real, unified thing. It’s a conceptual shorthand we’ve used for decades that doesn't hold up under modern fMRI scrutiny. Brain regions are constantly multitasking. Your "visual cortex" doesn't just see; it reacts to touch and sound too.

Scientists used to rely on Brodmann areas. In 1909, Korbinian Brodmann mapped the cerebral cortex into 52 distinct regions based on cell structure. We still use these numbers today. If a surgeon says "Area 44," they mean Broca's area. But even Brodmann knew his map was a simplification. We’ve spent a century trying to make the brain fit into neat little boxes because it makes us feel like we understand it.

What Modern Imaging Actually Shows Us

We’ve moved past static drawings. Now, we have Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI). Instead of showing the "blobs" of the brain, DTI shows the wiring. It tracks the movement of water molecules along white matter tracts.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Care at Texas Children's Pediatrics Baytown Without the Stress

- White Matter: The "cables" connecting different cities.

- Gray Matter: The "cities" where the processing happens.

When you look at DTI images of parts of the brain, it looks like a neon rainbow of yarn. These images represent the connectome. This is the new frontier. We are realizing that the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala is often more important than the parts themselves.

If those cables are frayed, it doesn't matter how healthy the "parts" look. This is why some people have perfectly normal-looking CT scans but suffer from devastating traumatic brain injuries. The map looks fine, but the roads are washed out.

The Myth of the Left Brain vs. Right Brain

We need to kill this myth. You aren't "left-brained" because you like math. You aren't "right-brained" because you paint.

Looking at functional MRI (fMRI) images of parts of the brain during complex tasks shows total global activation. If you’re solving a logic puzzle, both hemispheres are chatting. If you're writing a poem, your "logical" left side is processing the syntax while your "creative" right side handles the metaphor. They are tied together by the corpus callosum, a massive bridge of 200 million nerve fibers. Cutting that bridge is one of the only ways to actually see the hemispheres work in isolation, a radical surgery sometimes used for extreme epilepsy.

How to Read a Brain Scan Without Being a Doctor

If you're looking at a clinical image—maybe your own or a family member's—it's easy to freak out over a dark spot. Don't.

Ventricles are a great example. These are the "holes" in the middle of the brain. On many images of parts of the brain, they look like scary black voids. In reality, they are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). They’re supposed to be there. They cushion your brain so it doesn't turn into mush when you trip on the sidewalk.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Healthiest Cranberry Juice to Drink: What Most People Get Wrong

However, if those ventricles look too big, it might indicate hydrocephalus or even the brain-shrinking effects of Alzheimer’s. It’s all about proportion.

Then you have the sulci (the grooves) and the gyri (the bumps). As we age, the grooves get wider. It’s called atrophy. Everyone gets it to some degree. It’s like wrinkles, but for your thoughts.

Why 3D Renderings Can Be Misleading

Medical illustrators have a tough job. They have to make the brain look "readable." This usually means stripping away the meninges—the three protective layers that actually wrap the brain.

- Dura Mater: Tough and leathery.

- Arachnoid Mater: Looks like a spiderweb.

- Pia Mater: A thin, shrink-wrapped skin.

Most images of parts of the brain ignore these. They also ignore the massive network of blood vessels. Your brain is a blood hog. It uses 20% of your body's oxygen despite being only 2% of your weight. If an image doesn't show the "Circle of Willis"—the circular graveyard of arteries at the base—it’s missing the plumbing that keeps the lights on.

The Future: PET Scans and Molecular Imaging

The coolest images of parts of the brain aren't about structure; they're about chemistry. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans can track specific proteins.

In research for diseases like Parkinson's, scientists use tracers that bind to dopamine receptors. You can literally see the "fading out" of dopamine in the substantia nigra. It's haunting. You're looking at the physical disappearance of the chemical that allows a person to move and feel pleasure.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Hybrid Athlete Training Program PDF That Actually Works Without Burning You Out

We are also getting better at seeing "tau" and "amyloid" plaques. These are the hallmarks of Alzheimer's. For a long time, you could only truly diagnose Alzheimer's after someone died by looking at their brain under a microscope. Now, we can see the buildup in a living person. It’s not a perfect diagnostic tool yet, but it’s getting there.

Practical Insights for the Curious

If you are looking at images of parts of the brain for educational or personal reasons, keep these nuances in mind. Context is everything.

- Ignore the colors: In fMRI, the "orange" spots don't mean that part of the brain is "lighting up" like a bulb. It just means there is a statistically significant increase in oxygenated blood flow compared to a resting state. It's a calculation, not a photo.

- Scale matters: A tiny lesion in the brainstem (the "reptilian" part that controls breathing) is way more dangerous than a larger lesion in the frontal lobe. Location is more important than size.

- Plasticity is real: The brain is "plastic." If one part is damaged, other parts can sometimes learn to take over its job. You can’t see this on a static image, but you can see it in "before and after" functional maps over years of recovery.

Basically, your brain is a dynamic, shifting electric storm. Static images of parts of the brain are just snapshots of a lightning bolt mid-strike. They tell you where the energy was, but they don't tell the whole story of the storm.

To truly understand neuroanatomy, stop looking for "the spot where X happens." Start looking for the pathways. Start looking at how the prefrontal cortex—the CEO of your head—manages the unruly employees in the deeper, older structures.

The most accurate "map" of your brain isn't a picture at all; it's the sum total of your actions, memories, and the weird way you laugh at jokes. No MRI can capture that yet.

If you're trying to learn more, look for "atlases" created by universities like the University of British Columbia or the Allen Brain Institute. These use real tissue samples and high-resolution digital slicing. They aren't as "pretty" as the ones in textbooks, but they are honest. They show the grainy, complex reality of the three-pound universe sitting behind your eyes.

Start by identifying the major landmarks: the Central Sulcus, which divides movement from sensation, and the Sylvian Fissure, which tucks away the temporal lobe. Once you find those "anchors," the rest of the geography starts to make sense.

Next time you see a viral "brain scan" claiming to show "the brain on love" or "the brain on coffee," look at the fine print. Usually, it's just showing a tiny change in blood flow in the nucleus accumbens. Interesting? Yes. The whole story? Not even close.