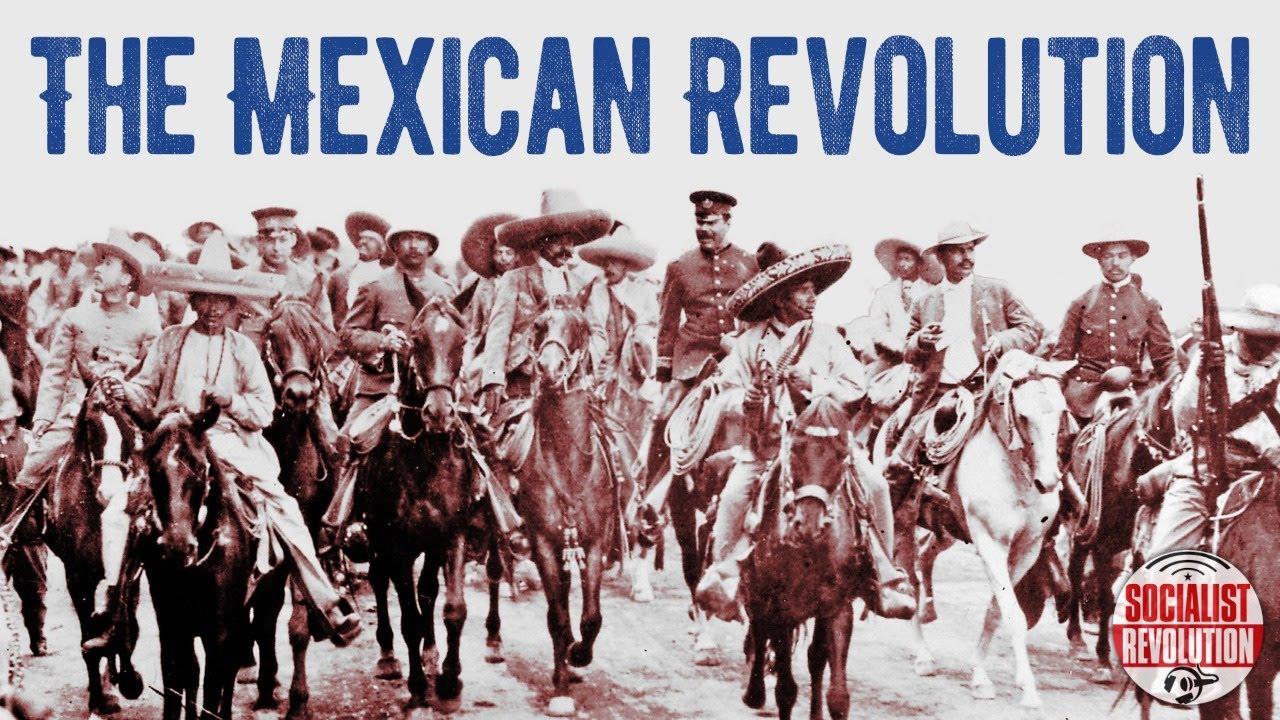

Honestly, when most people think about the 1910 conflict in Mexico, they see a grainy, sepia-toned blur of big hats and dusty horses. It’s a vibe. But the images of Mexican Revolution history we see today aren't just "cool old photos." They were actually the world’s first real taste of a "media war." This wasn't some quiet, isolated civil war; it was a gritty, high-stakes spectacle captured by photographers who were literally dodging Mauser bullets to get the shot.

You’ve probably seen the famous shot of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata sitting in the presidential chairs in Mexico City. Villa looks like he’s having the time of his life, grinning ear to ear. Zapata? He looks like he’d rather be anywhere else, clutching his rifle like a lifeline. That single frame tells you more about the friction between the north and the south than a five-hundred-page textbook ever could.

The revolution was messy. It was a chaotic scramble for "Tierra y Libertad" (Land and Liberty), and because the Kodak Brownie had recently become a thing, the whole world watched it happen in near real-time.

Why These Photos Look the Way They Do

Ever wonder why everyone looks so stiff? It wasn't just because they were "tough." Early 20th-century film was slow. If you moved, you blurred. But by 1910, technology was shifting. We started seeing more candid shots—soldiers eating at a railway station, women (soldaderas) peering out of train cars, and the grim reality of the firing squads.

The images of Mexican Revolution fighters weren't just for art. They were propaganda. Rebels and federales alike knew that if they looked powerful in a photo, it might influence the American government across the border. They basically invented "optics" before the word was even a thing in politics.

Photographers like Agustín Víctor Casasola became legends because they realized this was a goldmine. The Casasola Archive in Pachuca, Mexico, holds over 500,000 images. It’s a massive, dusty treasure trove. If you’ve seen a photo of the revolution, there is a roughly 90% chance it came from the Casasola family. They were everywhere. They captured the hunger, the dirt, and the weirdly formal way people dressed to go to war back then.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

The Mystery of the Soldaderas

We need to talk about the women. You see them in the background of so many images of Mexican Revolution scenes, usually lugging pots, pans, and extra ammo. These weren't just "camp followers." They were the backbone of the entire movement.

Some photos show them with crossed ammunition belts (bandoliers) over their dresses. Others show them disguised as men, like Petra Herrera, who led a brigade of hundreds but had to pretend to be "Pedro" just to get the respect she deserved. When you look at these photos, look at their eyes. There’s a specific kind of exhaustion there that transcends the black-and-white film.

The American Obsession with the Border War

It wasn't just Mexican photographers on the scene. American news outlets were obsessed. They sent guys like Jimmy Hare and even silent film crews to follow Pancho Villa.

Villa was a genius at branding. He actually signed a contract with the Mutual Film Corporation in 1914. He basically agreed to fight his battles during the day so the cameras had enough light to film him. Think about that for a second. A warlord was scheduling his revolution around "golden hour" for better production value.

That’s why so many images of Mexican Revolution leaders look so iconic. They were literally posing for a global audience. They wanted to look like the heroes of a Western movie, and the American public ate it up. This created a weird bridge between real-life violence and entertainment that we’re still dealing with today in the age of social media.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

The Grim Side of the Lens

Not everything was a posed portrait. Some of the most haunting images are the "postcard" photos. Believe it or not, people used to buy postcards of executions. It sounds morbid—because it is—but there was a huge market for it in the U.S. and Europe.

You'll see photos of the "Decena Trágica" (the Ten Tragic Days) where Mexico City’s streets were littered with debris and bodies. These images weren't filtered. They showed the shattered glass, the dead horses, and the hollowed-out buildings. It’s a stark reminder that behind the romanticized image of the "charro" rebel, there was a country being ripped apart at the seams.

Identifying the Real Deal

If you’re looking at images of Mexican Revolution archives, you have to be careful. A lot of movie stills from the 1930s and 40s get passed off as real historical photos.

Real photos from the era usually have a specific grain. They have imperfections. You’ll see "light leaks" or chemical stains on the edges. Also, look at the equipment. If the soldiers are carrying rifles that look a bit too modern for 1915, it’s probably a fake or a later reenactment. The Mauser 1893 and the Winchester carbine were the stars of the era. If the gear doesn't match the year, the photo is lying to you.

How to Explore the History Yourself

If this has sparked a rabbit hole for you, don’t just stick to Google Images. Most of those are low-res and poorly captioned.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Check out the Sinafo (Sistema Nacional de Fototecas) in Mexico. It’s the official national archive. You can search through thousands of digitized plates. Another great spot is the Library of Congress in the U.S., which has a massive collection of photos taken by American journalists along the border.

You should also look for the work of Hugo Brehme. He was a German-born photographer who took some of the most beautiful, almost pictorialist photos of the Mexican landscape and its people during the war. His stuff looks more like art than journalism, focusing on the lighting and the epic scale of the mountains.

A Quick Reality Check on "Colorized" Photos

You’ll see a lot of colorized versions of these photos on Instagram or Twitter. They’re cool, sure. They make the history feel "closer." But remember that the colors are often guesses. That "brown" jacket might have actually been a faded green or a dusty grey. Colorization is an interpretation, not a fact. Always try to find the original monochrome version to see what the photographer actually saw through the viewfinder.

Taking Action: Where to Go Next

To really understand the visual history of this era, you have to look beyond the "great men" like Villa and Zapata.

- Search for "La Adelita" imagery: Find the photos of the anonymous women who kept the rail lines running and the troops fed.

- Visit the National Museum of the Revolution if you're ever in Mexico City. It’s located right under the Monument to the Revolution, and the photo galleries are hauntingly good.

- Analyze the backgrounds: Stop looking at the faces for a second. Look at the children in the corners of the frames. Look at the state of the adobe walls. That’s where the real story of 1910 lives.

The revolution ended a long time ago, but these images keep the tension alive. They aren't just snapshots; they are the DNA of modern Mexico. Studying them isn't just about looking at the past—it's about seeing how a nation decided to show itself to the world for the first time.