Mars isn't red. Well, it is, but not the way you see it in the movies. If you spent your afternoon scrolling through images of Mars rovers, you’ve probably noticed something weird. Some photos look like a dusty afternoon in Arizona. Others look like a psychedelic fever dream with neon blue rocks and purple skies.

It’s confusing.

Scientists aren't trying to trick you. They’re just looking for things your eyes can't see. When Curiosity or Perseverance beams data back to the Deep Space Network, it isn't sending a JPEG file like your iPhone does. It’s sending raw data packets that have to be stitched together, color-corrected, and sometimes intentionally distorted to highlight geological features. It’s a messy, fascinating process that blurs the line between photography and data science.

Honestly, the "true color" of Mars is actually a bit of a debate among imaging specialists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

How we actually get images of Mars rovers to Earth

Getting a high-resolution selfie from 140 million miles away is a nightmare of physics. You've got limited bandwidth. You've got cosmic rays that can flip bits in the memory. You've got a window of time where the orbiters—like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter—are actually in the right position to act as a relay.

Most images of Mars rovers start as grayscale. The cameras use filters.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Specifically, the Mastcam-Z on Perseverance uses a filter wheel. It snaps the same frame multiple times through different colored glass. Red. Green. Blue. Infrared. When these are combined, you get a "true color" image, or at least the closest thing to what a human standing in Jezero Crater would see. But "human vision" is subjective. Dust in the Martian atmosphere scatters light differently than Earth's nitrogen-rich air. This causes a phenomenon called "Mie scattering." On Earth, our sky is blue and our sunsets are red. On Mars? The sky is a butterscotch pink during the day, and the sunsets are blue.

If you see an image where the sky looks Earth-blue, that’s "white-balanced." It’s a trick scientists use to make the rocks look like they would under Earth’s lighting. It helps geologists identify minerals they recognize from field work in places like Iceland or the Australian outback.

The selfie stick you can't see

People always ask: "Who is taking the picture of the rover?"

It looks like a floating drone is hovering nearby. It isn't. (Except for that one time Ingenuity took a photo of Perseverance). Usually, those iconic images of Mars rovers are composites. The rover uses the robotic arm to take dozens of overlapping shots. Then, clever software at JPL stitches them together and digitally removes the arm from the final frame.

It’s the ultimate Instagram move.

🔗 Read more: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

The evolution of Martian photography

We’ve come a long way since 1976. The Viking 1 lander sent back the first successful images from the surface. They were grainy. They were yellow. People were just happy to see rocks.

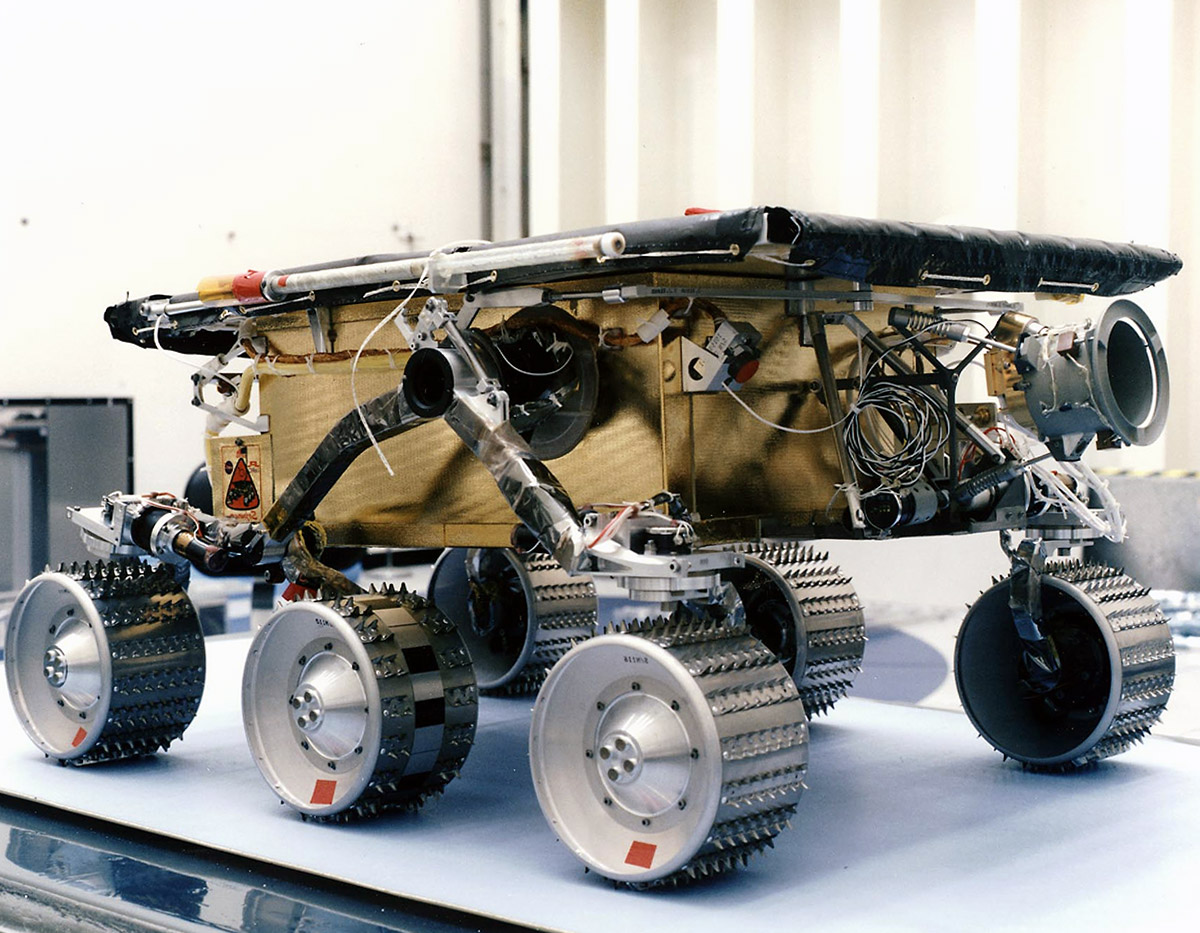

Then came Sojourner in 1997. It was tiny, the size of a microwave. The images were better, but still limited. By the time Spirit and Opportunity landed in 2004, we started getting "pancam" views that felt immersive. These rovers were the marathon runners of the solar system. Opportunity was supposed to last 90 days. It lasted 15 years. Because of that longevity, we have a massive archive of images of Mars rovers showing the changing seasons and the terrifying buildup of "dust devils" on the solar panels.

Curiosity changed the game in 2012. It brought the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI). This thing can see grains of sand. It can see the texture of a drill hole.

Why some photos look like "False Color" garbage

You’ll occasionally find a photo that looks like a 1990s rave. This is "False Color" imaging. It’s not for aesthetics. Scientists use near-infrared and short-wave infrared filters to map mineralogy. Hematite might show up as bright purple. Clay minerals might look green. If you're a scientist looking for signs of ancient water, you don't care about "true color." You care about where the magnesium-rich olivine is hiding.

The psychological impact of seeing the Red Planet

There is something deeply moving about seeing a wheel track in the dust. It’s a human mark on a world that hasn't seen a drop of rain in billions of years. When we look at images of Mars rovers, we aren't just looking at robots. We are looking at ourselves. We’re looking at our curiosity—literally and figuratively.

💡 You might also like: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

We see "pareidolia" everywhere. This is the human tendency to see familiar shapes in random patterns. It’s why people claim to see a "face on Mars" or a "Martian Bigfoot" or "discarded spoons" in rover photos. In reality, it’s just wind-sculpted basalt. But our brains want it to be more.

The raw power of the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera is worth mentioning here too. It’s on the orbiter, not the rover. But it’s powerful enough to take photos of the rovers from space. Seeing a tiny white speck (Perseverance) in the middle of a massive, ancient river delta really puts our place in the universe into perspective. It's tiny. We're tiny.

Troubleshooting common misconceptions about Mars photos

- "The colors are faked to make it look like Earth." Actually, it's often the opposite. NASA often has to "warm up" the images because the raw data can look very cold and blue-heavy.

- "There are no stars in the background."

This is a classic conspiracy theory trope. Rover cameras are exposed for the bright Martian surface. The sun, while further away, is still very bright. To see stars, you’d need a long exposure that would completely blow out (overexpose) the rover and the ground. - "The images are delayed by hours." Light travels fast, but not instantly. Depending on where the planets are in their orbits, it takes between 3 and 22 minutes for a signal to reach us. So, when you see a "live" stream of a landing, you're actually watching history that already happened.

Making sense of the raw data

If you want to be a pro at looking at these, go to the source. NASA's Raw Image feed is public. You can see the photos before they get the "Hollywood" treatment.

- Check the timestamp: Look for the "Sol" number. That’s the Martian day count since the rover landed.

- Look for the calibration target: Most rovers carry a "Sun Dial" or a color palette. This has known colors (Red, Green, Blue, Yellow) and even little pieces of mirrors. This allows the software to adjust for the specific lighting conditions of that specific day.

- Note the shadows: Long shadows mean the photo was taken at the start or end of a Sol. This is often when the "blue sunset" effect is most visible.

Actionable steps for the armchair explorer

Don't just look at the "Picture of the Day." Dig deeper into the archives to understand the context of what these machines are actually doing.

- Visit the NASA Raw Image Gallery: Both the Curiosity and Perseverance missions have dedicated portals where every single raw frame is uploaded as it arrives. You can see the "ugly" photos—the ones with lens flares, blurry focus, and motion smear.

- Use the interactive maps: Tools like "Explore with Perseverance" allow you to see exactly where a photo was taken within the Jezero Crater. This spatial context changes how you perceive the landscape.

- Learn to read a histogram: If you’re into photography, look at the light distribution. Martian images are often very "flat" because the atmosphere is thin and the light is harsh.

- Follow the "Image Processing" community on social media: There are independent experts like Emily Lakdawalla or Kevin Gill who take raw data and create stunning, high-fidelity mosaics that often surpass the official releases in artistic quality.

The most important thing to remember is that an image is a tool. Whether it’s a wide-angle 360-degree panorama of the Gale Crater or a microscopic view of a rock nicknamed "Lighthouse Lamb," these photos are the only way we can experience a world that would kill us in seconds if we stood there unprotected. They are our eyes in the dark. And even if the colors are a little "off" sometimes, they are the most honest look at our neighbor we've ever had.