Look at the Moon on a clear night and it feels close enough to touch. It’s right there. Big, silver, and covered in those familiar gray splotches we call "seas." But if you’re looking for the American flags or the base of the Eagle lander with a backyard telescope, you’re going to be disappointed. You won't find them. It’s physically impossible.

The physics of light is a stubborn thing. To see the Apollo 11 descent stage from your driveway, you’d need a telescope roughly 75 feet wide. Even the Hubble Space Telescope, orbiting high above Earth's blurry atmosphere, can't resolve something as small as a lunar module. To Hubble, the Apollo sites are just a few pixels of gray.

That hasn't stopped the rumors, though. For decades, people have swapped blurry photos and grainy crops, arguing over what’s a rock and what’s a man-made relic. But things changed in 2009. That was the year NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) reached its destination. It didn't just take pictures; it changed the game.

The LRO changed how we look at images of lunar landing sites

The LRO orbits the Moon at a dizzying speed, but it flies low—sometimes just 31 miles above the surface. Its camera, the LROC, has captured images of lunar landing sites with enough clarity to make out the dual-tone contrast of the lunar rover's wheel tracks. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. Those tracks have been sitting there, undisturbed by wind or rain, for over fifty years.

Take a look at the shots of the Apollo 11 site in the Sea of Tranquility. You can see the Lunar Module "Eagle" sitting there like a tiny, angular speck. But the most human part isn't the metal. It’s the dark, winding trails. Those are the "beaten paths" created by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they walked to the Little West Crater.

The lunar soil, or regolith, is actually quite delicate. When the astronauts walked on it, they scuffed up the top layer, revealing darker material underneath. In the LRO photos, these paths look like messy pencil sketches on a dusty floor. It’s evidence of human presence that feels weirdly intimate, even from fifty miles up.

Why some photos look "fake" to the untrained eye

A lot of people get tripped up by the shadows. In many images of lunar landing sites, the shadows look incredibly long and distorted. This isn't a Hollywood lighting mistake. It’s a result of the Sun being low on the lunar horizon when the LRO passes over. Since the Moon has no atmosphere to scatter light, shadows are pitch black and razor-sharp.

👉 See also: Pi Coin Price in USD: Why Most Predictions Are Completely Wrong

There's also the issue of the "shimmer." Sometimes, the descent stages look like they’re glowing or reflecting light in a way that feels unnatural. That’s because these crafts were covered in Kapton—that gold-colored, crinkly thermal insulation. Even after decades of solar radiation, that material is still more reflective than the dull, volcanic basalt of the lunar plains.

It's not just about the Americans anymore

While the Apollo sites are the most famous, they aren't the only footprints on the Moon. We’re in a new era. China’s Chang'e missions have been dropping landers and rovers like clockwork. The Chang'e 4 mission, which landed on the far side of the Moon (the side that never faces Earth), provided some of the most hauntingly beautiful images we've ever seen.

The far side is rugged. It’s mountainous and battered by craters. Seeing the Yutu-2 rover in those images—a tiny white dot against a landscape that hasn't changed in billions of years—really puts things in perspective.

Then you have the crash sites. Not every landing is a soft one. In 2019, India’s Vikram lander and Israel’s Beresheet both met a violent end on the lunar surface. The LRO team actually spent weeks hunting for the impact sites. When they finally found them, the images showed a literal debris field. Tiny shards of metal scattered across the gray dust. It’s a stark reminder that space is hard. Really hard.

The technical hurdles of photographing the Moon

You might wonder why we don't have 4K live streams of these sites 24/7. It basically comes down to bandwidth and power. Sending high-resolution data back to Earth takes a massive amount of energy. Most orbiters have to prioritize scientific data—spectroscopy, gravity mapping, and altitude measurements—over "tourist shots."

Also, the Moon is a harsh place for a camera. The temperature swings are brutal. We're talking 250 degrees Fahrenheit in the sun and minus 200 in the shade. The electronics have to be shielded, which adds weight and cost. Every gram of a camera's sensor has to be justified by the science it will produce.

✨ Don't miss: Oculus Rift: Why the Headset That Started It All Still Matters in 2026

Dr. Mark Robinson, the Principal Investigator for the LROC, has spoken at length about the challenges of identifying objects in these photos. Sometimes, a rock is just a rock. But when you align the LRO photos with the surface photos taken by the astronauts themselves, the math doesn't lie. You can match a specific boulder in an Apollo 17 photo to a specific pixel in a satellite image. That kind of cross-referencing is what proves these images are the real deal.

The debate over "Heritage Sites"

There’s a growing conversation about what these images mean for the future. As private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin eye the Moon, people are getting worried. Should we protect the Apollo 11 site? Should it be a "No-Fly Zone"?

If a rocket lands too close to the Sea of Tranquility, the engine plume could blast lunar dust at high speeds. That dust acts like sandpaper. It could literally sandblast the original footprints and the American flag into oblivion. This isn't just theory. When Apollo 12 landed near the Surveyor 3 probe, it pitted the older craft with tiny craters.

Images of lunar landing sites are now being used by organizations like "For All Moonkind" to map out these historic zones. They want to create a framework for heritage preservation. Honestly, it’s a weirdly modern problem to have: how do we keep from ruining our own history on another world?

How you can find these images yourself

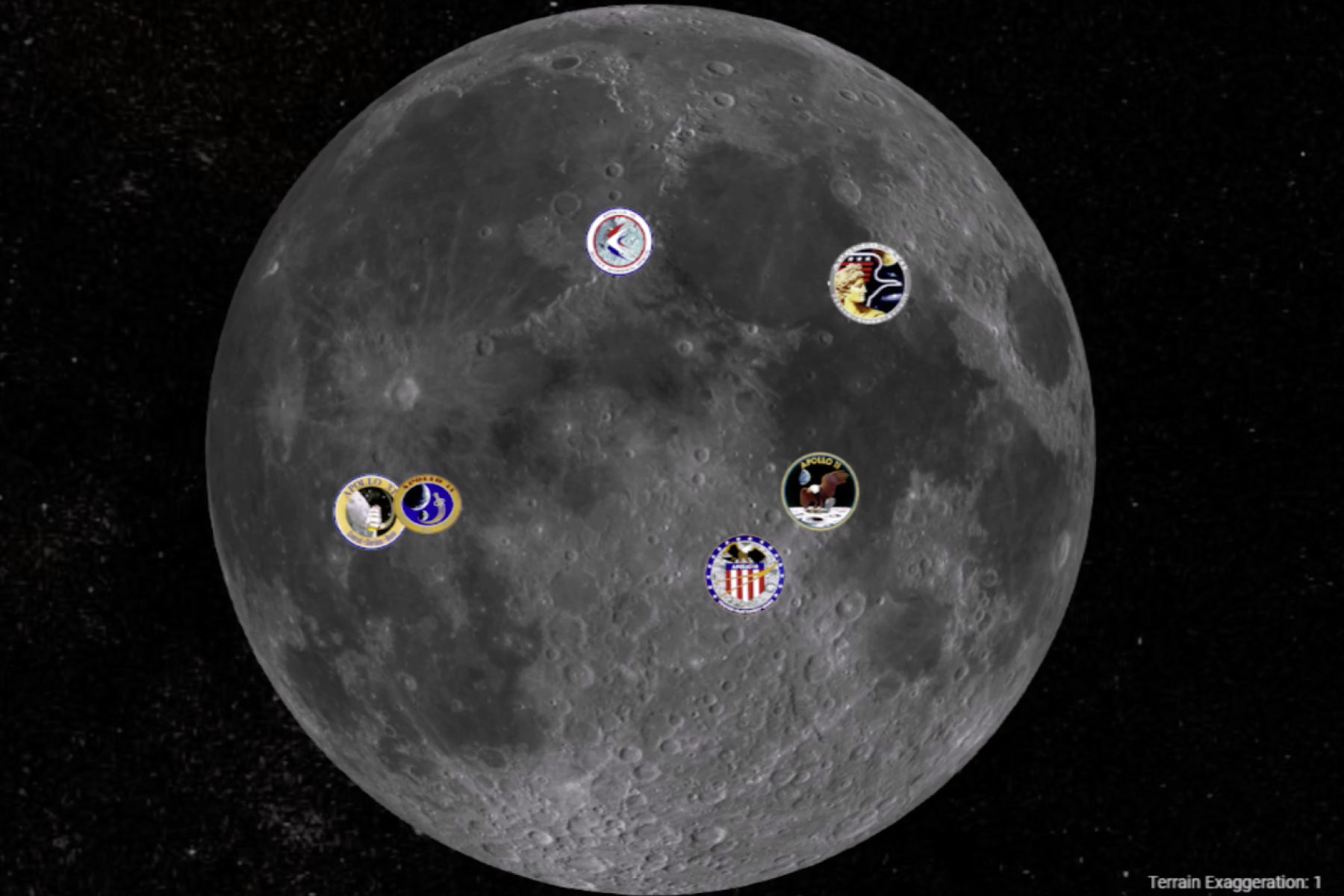

You don't need a security clearance to see these. NASA is actually pretty great about making its archives public. The LROC website has an interactive map called "QuickMap." It’s basically Google Earth but for the Moon.

You can zoom in on the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 sites. You can find the Lunokhod rovers left by the Soviet Union. You can even see the "grave" of the Saturn V third stages that were intentionally crashed into the Moon to calibrate seismometers.

🔗 Read more: New Update for iPhone Emojis Explained: Why the Pickle and Meteor are Just the Start

- Apollo 15 (Hadley-Apennine): This is arguably the most scenic site. The lander sits right next to the massive Hadley Rille, a giant lava channel. The LRO photos show the tracks where the astronauts drove the Lunar Roving Vehicle right to the edge of the canyon.

- The "Man in the Moon": Use the high-res mosaics to see how the lighting changes during a lunar day. The craters look totally different when the sun is directly overhead versus when it's at an angle.

- Chang'e 5: Look for the site in the Oceanus Procellarum where China collected samples and blasted back off. You can see the distinct "scorch mark" from the ascent engine.

Realities of the "Missing" Flags

One of the most frequent questions people ask when looking at images of lunar landing sites is: "Where are the flags?"

In the Apollo 11 photos, you can't see the flag because it was actually blown over during takeoff. Neil Armstrong reported seeing it fall as the Eagle's ascent engine ignited. For the other missions, the LRO images show something fascinating. The flags are still there, casting tiny, thin shadows.

However, they aren't the stars and stripes anymore. Decades of unfiltered ultraviolet light have almost certainly bleached the nylon white. If you stood next to the Apollo 12 flag today, it would likely look like a white flag of surrender. It’s a ghost of a flag, standing in a vacuum.

What to do next if you're a space nerd

If this stuff fascinates you, don't just look at the low-res social media crops. Go to the source. The Arizona State University LROC image gallery is a goldmine. They have the "Featured Image" section where they explain exactly what you're looking at, from "swirls" of mysterious magnetism to the "pit craters" that might lead to underground lava tubes.

You should also check out the "Apollo Lunar Surface Journal." It’s a massive project that pairs the LRO images with the original transcripts of the astronauts' conversations. Reading what Buzz Aldrin said while looking at the exact crater you can see in a satellite photo is a surreal experience. It bridges the gap between the 1960s and the 2020s.

The Moon isn't a dead rock. It's a museum. And thanks to modern imaging technology, we finally have the "eyes" to walk through its halls without leaving our desks.

Actionable Insights for Amateur Observers:

- Download the LROC QuickMap: Use the "Layers" tool to toggle between different lighting conditions to see how shadows reveal or hide landers.

- Verify with coordinates: Don't trust "UFO" blogs. Cross-reference any "strange object" with the official Apollo landing coordinates ($0.67408^{\circ} N, 23.47297^{\circ} E$ for Apollo 11).

- Monitor Artemis updates: NASA's Artemis program will be taking new images of lunar landing sites as they scout for the next crewed landing near the lunar South Pole.

- Support preservation: Follow groups like For All Moonkind to understand the legal battle to protect these sites as "off-world" heritage locations.