You’ve probably stared at a grainy, black-and-white printout in a podiatrist's office and wondered if that's actually your body. It looks like a mess of pebbles and sticks. Honestly, it kind of is. The human foot is a mechanical nightmare—or a masterpiece, depending on whether you're currently dealing with a stress fracture. When you look at images of bones in the foot, you aren't just looking at a static structure. You're looking at 26 bones, 33 joints, and over a hundred muscles, tendons, and ligaments all trying to coordinate so you don't fall over while reaching for the milk.

Most people think their feet are just blocks of bone. Nope.

If you've ever seen a standard anatomical diagram, it’s all clean lines and labeled parts like the "calcaneus" or the "talus." But real life is messy. Real X-rays show bone spurs, varying densities, and sesamoids—those tiny pea-shaped bones under your big toe—that sometimes look like they're floating in space. Understanding what you're seeing in these images matters because, frankly, foot pain is one of the most common reasons people lose their mobility as they age.

What the charts don't tell you about images of bones in the foot

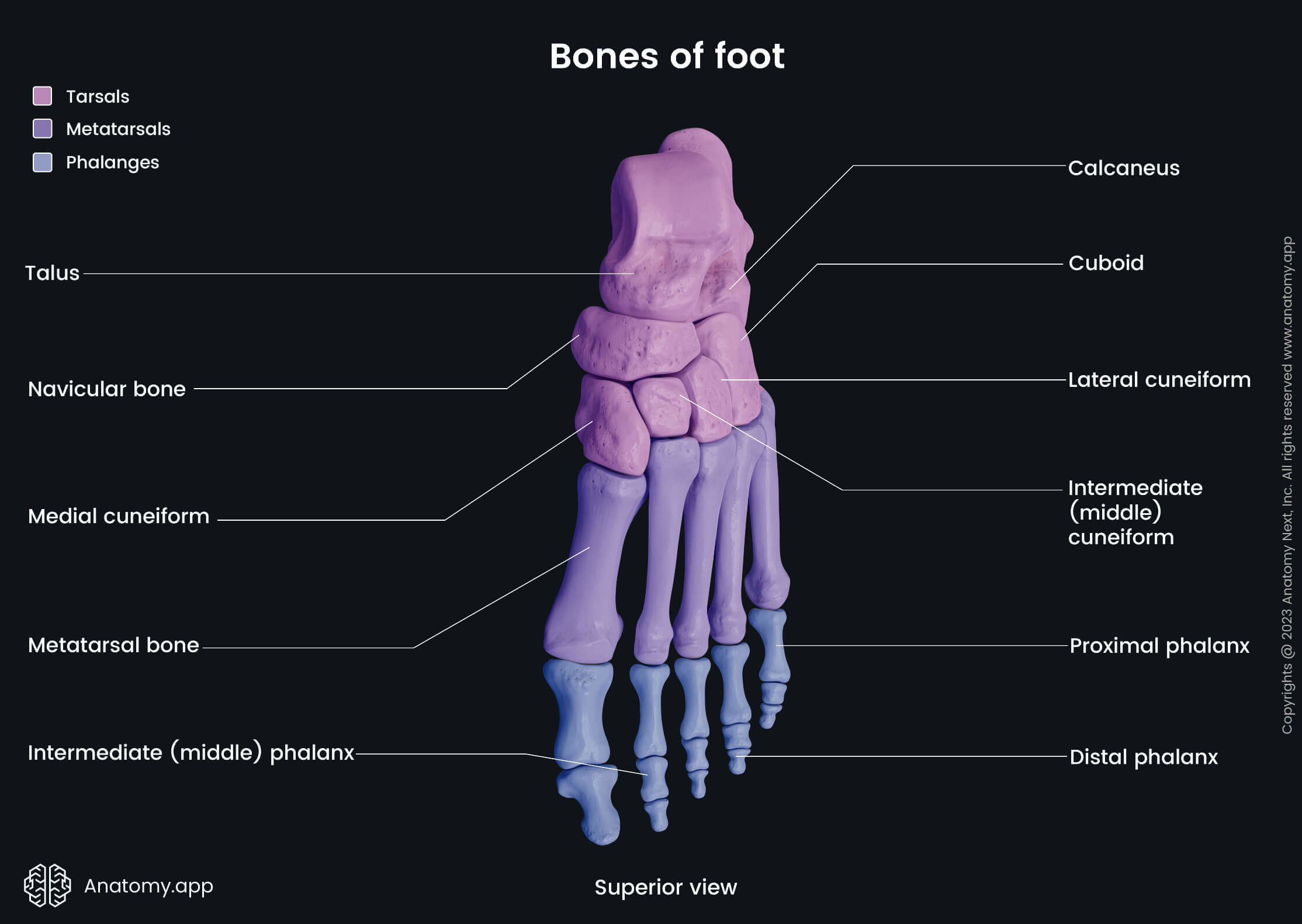

Standard medical illustrations are "perfect." Your feet are not. One of the biggest shocks people get when looking at clinical images of bones in the foot is the sheer complexity of the midfoot. This area, known as the tarsus, contains seven bones that fit together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle.

There's the talus, which sits right on top and connects your leg to your foot. Below that is the calcaneus—your heel bone. It’s the biggest bone in the foot and takes the brunt of every step you take. Then you have the navicular, the cuboid, and the three cuneiform bones.

Why does this matter? Because if one of these tiny, awkwardly shaped bones shifts even a millimeter, the entire "bridge" of your arch can collapse.

💡 You might also like: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

Experts like Dr. Kevin Kirby, a renowned podiatrist and pioneer in foot biomechanics, often point out that the way these bones appear on an image changes drastically based on whether you are standing or sitting. An X-ray of a foot "in the air" is almost useless for diagnosing functional issues like overpronation. You need to see how those bones behave under the weight of your entire body. When you look at weight-bearing images of bones in the foot, you might see the joints compress or the arch flatten out in a way that perfectly explains why your knees hurt after a three-mile walk.

The mystery of the accessory bones

Sometimes, people look at their X-rays and freak out because they see an "extra" bone. It looks like a break. It's often not.

About 10% to 15% of the population has what's called an os tibiale externum or an accessory navicular. It’s basically an extra piece of bone or cartilage located on the inner side of the foot, just above the arch. In an image, it looks like a chip has broken off the navicular bone. If your doctor doesn't know what they're looking at—or if you're trying to self-diagnose via Google Images—you might think you have a fracture. In reality, you were just born that way. It’s a quirk of evolution.

Why "normal" is a lie in podiatry

I’ve seen dozens of people compare their X-rays to the "normal" ones they find on Wikipedia. Stop doing that.

Bone density varies. Age changes things. If you’ve spent twenty years wearing high heels or tight work boots, your images of bones in the foot will reflect that. You’ll see the hallux (the big toe) starting to lean toward the other toes. That’s the beginning of a bunion, or hallux valgus. On an X-ray, the space between the first and second metatarsal widens, and the joint itself starts to look angry and jagged.

📖 Related: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

Then there are the metatarsals themselves. There are five of them. They are long, thin, and surprisingly fragile.

- The first metatarsal is thick because it handles the "push-off" phase of walking.

- The second and third are more fixed and rigid.

- The fifth metatarsal—the one on the outside—is the one most likely to snap if you roll your ankle.

When you look at images of these bones, look for the "cortex," the bright white outer edge of the bone. If that white line has a tiny, dark crack in it, you're looking at a stress fracture. These are notoriously hard to see on standard X-rays early on. Often, a doctor won't see the fracture itself until it starts to heal and a "callus" of new bone—which looks like a fuzzy white cloud—appears on the image a few weeks later.

The role of the sesamoids

Don't ignore the tiny guys. Underneath the head of the first metatarsal are two tiny bones called sesamoids. They’re embedded in the tendons. Think of them like kneecaps for your big toe. In images of bones in the foot, they look like two little seeds. If one is split in two, it might be a fracture, or it might just be a "bipartite sesamoid," which is just another natural variation.

Technology has changed how we view foot anatomy

We aren't just stuck with flat 2D X-rays anymore. Weight-bearing CT (Computed Tomography) scans are the new gold standard.

Unlike a traditional CT where you lie down, these machines allow you to stand up while the image is taken. This captures the three-dimensional relationship between the bones while they are actually doing their job. It’s a game-changer for surgeons. Seeing how the talus rotates inside the ankle mortise under pressure allows for much more precise surgeries.

👉 See also: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

If you are looking at images of bones in the foot to understand a chronic injury, a 2D lateral view (from the side) only tells half the story. You need the "AP" view (top-down) and the oblique view (at an angle) to see the gaps between the joints. If those gaps are gone, you’re looking at arthritis. The cartilage has worn away, and the bones are literally grinding against each other. On an image, this looks like "bone-on-bone" contact, often with white, sclerotic edges where the bone has hardened in response to the friction.

Practical steps for interpreting your own foot images

If you’re looking at your own medical records or trying to understand your foot health better, don't just focus on the bones themselves. Look at the alignment.

- Check the Meary’s Angle: Draw a line through the middle of the talus and another through the first metatarsal. In a "normal" foot image, these lines should basically be a straight line. If they angle downward, you have flat feet (pes planus). If they angle upward, you have high arches (pes cavus).

- Look for "Joint Space": There should be a clear, dark gap between every bone. That dark space is where your healthy cartilage lives. If the bones look like they are merging or "kissing," that’s where your pain is coming from.

- Identify the Fifth Metatarsal Base: If you’ve had an ankle sprain that won't heal, look at the very base of the bone on the pinky-toe side. A "Jones Fracture" occurs here and is famous for not healing well because that specific spot has a terrible blood supply.

- Observe the Heel Spur: Many people see a sharp hook of bone coming off the bottom of the calcaneus and panic. Actually, heel spurs aren't usually the cause of pain; the inflamed plantar fascia ligament attached to it is. The spur is just a sign that the ligament has been pulling on the bone for a long time.

Understanding images of bones in the foot is about recognizing that your feet are dynamic. They change with every step, every shoe choice, and every injury. Next time you see an X-ray, look past the labels. Look for the symmetry—or the lack of it. Compare your left foot to your right. Often, the "abnormality" on the painful foot is only obvious when you see how different it looks from the "good" foot.

Get a copy of your imaging. Ask your technician for the DICOM files, not just a paper printout. Use a free DICOM viewer on your computer to zoom in. You’ll see the trabecular patterns—the internal "honeycomb" structure of the bone—and you’ll start to realize just how complex those two things at the end of your legs really are. No two feet are the same, and your images are a map of your specific life and movement patterns. Use that map to talk to your doctor about functional goals, not just "fixing a bone." Focus on how those bones move together as a unit.

Next Steps for Foot Health Management

To move forward with your foot health, request a "weight-bearing" series of X-rays specifically, as non-weight-bearing images often mask the alignment issues that cause pain during movement. If you're reviewing existing images, locate the "joint space" between the talus and the calcaneus; narrowing here is a primary indicator of subtalar arthritis, which often requires specific orthotic intervention rather than just general cushioning. Finally, if a fracture is suspected but not visible on an X-ray, advocate for an MRI or a bone scan, as stress reactions in the metatarsals frequently remain invisible on standard film for up to four weeks after the onset of symptoms.