You’ve seen them. Those glossy, high-contrast images of bluefin tuna lying on the cold concrete of the Toyosu Market in Tokyo. They look like chrome-plated torpedoes. Massive. Almost robotic in their perfection. But honestly, most of the photos we scroll through on Instagram or see in sushi documentaries barely scratch the surface of what this fish actually is. It’s kinda wild how we’ve reduced one of the ocean's most sophisticated apex predators to a series of "food porn" shots or "big catch" trophies.

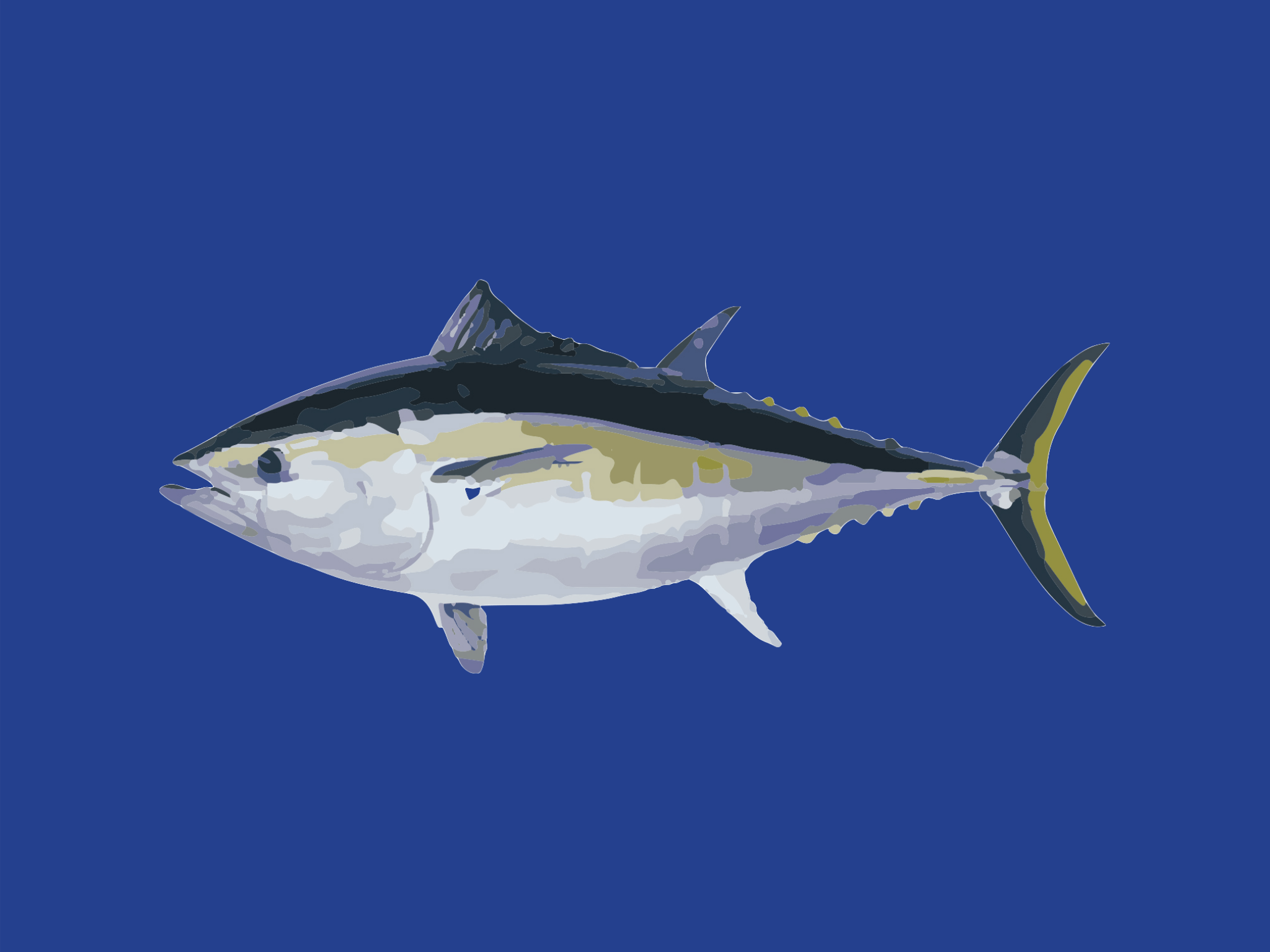

Bluefin tuna aren't just fish. They’re warm-blooded biological marvels. They can weigh as much as a grand piano and swim at speeds that would get you a ticket in a school zone. When you look at a photograph of a Pacific, Atlantic, or Southern bluefin, you're looking at an animal that has to keep moving its entire life just to breathe. If they stop, they die.

The problem with most digital photos

Most people searching for images of bluefin tuna are looking for one of two things: a massive fish hanging from a scale or a tray of fatty otoro sashimi. There’s a huge gap in between. We rarely see the iridescent purple and silver sheen they have while they’re still alive. That color fades the second they’re pulled out of the water. It’s a tragedy of physics, really. The oxygen stops hitting the blood-rich muscle, and that vibrant, neon glow turns into a dull grey-blue.

Photographers like Brian Skerry have spent years trying to capture them in their actual element. It’s hard. You’re trying to photograph a 600-pound bullet that doesn't want to be found. If you see a photo where the tuna looks like it’s glowing, that’s not Photoshop. That’s the real deal. They have this shimmering, metallic skin that reflects the ambient light of the open ocean in a way that looks almost digital.

Why images of bluefin tuna often look "fake" to the untrained eye

The scale is the first thing that messes with your head. You see a person standing next to a tuna and it looks like a forced-perspective trick. It isn't. The Atlantic bluefin (Thunnus thynnus) can reach lengths of over 10 feet. When you see a photo of a fisherman struggling to hold the head up, believe the struggle.

The anatomy is also weirdly specialized. If you look closely at high-resolution images of bluefin tuna, you’ll notice these tiny little spikes near the tail. Those are called finlets. They aren't just for show; they reduce turbulence. It’s hydrodynamics at a level that Formula 1 engineers study. Honestly, the more you look at the technical details of their bodies—the way their fins retract into slots to stay hydrodynamic—the more you realize they are built for one thing: speed.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

The dark side of the lens

There’s a lot of controversy surrounding how we document these fish. Conservation groups like PEW and the World Wildlife Fund often use heartbreaking images to highlight overfishing. You’ve probably seen the shots of dozens of tuna lined up like cordwood. These images serve a purpose, but they also create a disconnect. We start seeing the fish as a commodity rather than a creature.

Then you have the "tuna towers" and the high-end drone shots from fishing shows. These are exciting, sure. But they often miss the ecological nuance. A bluefin tuna isn't just a prize. It's a migratory wanderer that crosses entire oceans. They are the marathon runners of the sea.

Identifying the three main species in photos

Not all bluefin are created equal, though they look strikingly similar in low-res photos.

- Atlantic Bluefin: These are the giants. If the photo looks like the fish could swallow a Labrador retriever whole, it’s probably an Atlantic. They’re found from the Gulf of Mexico up to Newfoundland and across to the Mediterranean.

- Pacific Bluefin: Slightly smaller but equally fast. These are the ones usually featured in those high-end Japanese auction photos.

- Southern Bluefin: Found in the southern hemisphere’s colder waters. They are critically managed and often seen in Australian aquaculture photography.

If you’re looking at images of bluefin tuna and the fish has a yellowish tint on those finlets I mentioned earlier, you might actually be looking at a Yellowfin tuna. People mix them up all the time. Yellowfin are great, but they don't have the same "blocky" muscularity or the sheer mass of a true Bluefin.

The art of the "Sashimi Shot"

We have to talk about the food photography aspect because that’s where most of the "bluefin" traffic lives. Look at the marbling. Real bluefin otoro (the belly fat) looks like a high-end Wagyu steak. It’s pink, almost white in some places, with fine webs of intramuscular fat.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

If you see a photo of "bluefin" and the meat is a translucent, bright neon red with no fat? That’s likely either a different species or a very lean cut called akami. While akami is delicious, the "money shot" for photographers is always that fatty belly. Chefs like Jiro Ono have helped turn the visual of sliced tuna into a global icon of luxury. But remember, that deep red color in photos is often enhanced. In reality, the meat is a rich, blood-wine color because of the high myoglobin content. These fish are basically one giant muscle.

Getting the "Discovery" shot

If you’re a photographer trying to get your work featured, you need to move away from the dock. Google and Discovery audiences are moving toward "contextual" imagery. They want to see the bait balls. They want to see the "boil" on the surface when a school of tuna is feeding.

Tuna feeding frenzies are chaotic. The water looks like it’s boiling. This is because they use "ram ventilation"—they have to swim fast with their mouths open to force water over their gills. In photos, this looks like a terrifying, gaping maw. It’s actually just a fish trying to catch its breath while it eats.

What the data tells us about the visual demand

People are obsessed with the price tags. You’ll often see headlines like "Tuna sells for $3 million" accompanied by a photo of a single fish. It’s important to realize those are outlier events, usually the first auction of the year in Japan. It’s a PR stunt. Most bluefin don't cost as much as a house, but the photos make you think otherwise. This "wealth-porn" photography has actually made conservation harder because it increases the "trophy" status of the animal.

The technical side of the hunt

Taking images of bluefin tuna underwater requires specialized gear. You aren't just jumping in with a GoPro. Because they move so fast, you need a high shutter speed—at least 1/1000th of a second—to freeze the motion. And because they live in the "blue," color correction is a nightmare. Everything looks monochromatic unless you’re using powerful external strobes or filming in very shallow water during a surface feed.

📖 Related: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

The best shots usually come from spotter planes. Pilots fly over the ocean looking for the shimmer of a school. They radio the boats or the film crews. It’s a high-stakes game of hide and seek.

Actionable ways to use and find quality tuna imagery

If you’re looking for authentic visuals for a project or just because you’re a nerd for marine life, you’ve got to be picky. Don’t just grab the first thing on a stock site.

- Check the fins: If the pectoral fin (the one on the side) is really long and reaches past the second dorsal fin, it’s an Albacore, not a Bluefin. Don't get fooled.

- Look for the "Eye": Bluefin have relatively small eyes compared to their body size, especially when compared to Bigeye tuna. This is a classic mistake in stock photography tagging.

- Source from Scientific Databases: Sites like NOAA or the Monterey Bay Aquarium often have the most "honest" photos that haven't been over-saturated for social media.

- Understand the "Burn": In the fishing world, "burnt meat" is a real thing. If a tuna fights too hard for too long, its body temperature rises so high it literally cooks the meat from the inside out. In photos, this meat looks cloudy and opaque. High-quality images will show clear, gemstone-like flesh.

The next time you see images of bluefin tuna, look past the size. Look at the engineering. Look at the way the tail is shaped like a crescent moon for maximum efficiency. These animals are the peak of millions of years of evolution. They deserve to be seen as more than just a menu item or a heavy weight on a hook.

To find truly unique perspectives, start following marine biologists on social media rather than just "charter fishing" accounts. You'll see the migration patterns, the tagging process, and the underwater releases that show the fish in its true, vibrant state before the "fade" sets in. Focus on the iridescence on the dorsal side; that’s the fingerprint of a healthy, wild bluefin. Avoid images that look overly "reddened" in post-production, as they often mask the actual quality of the fish.