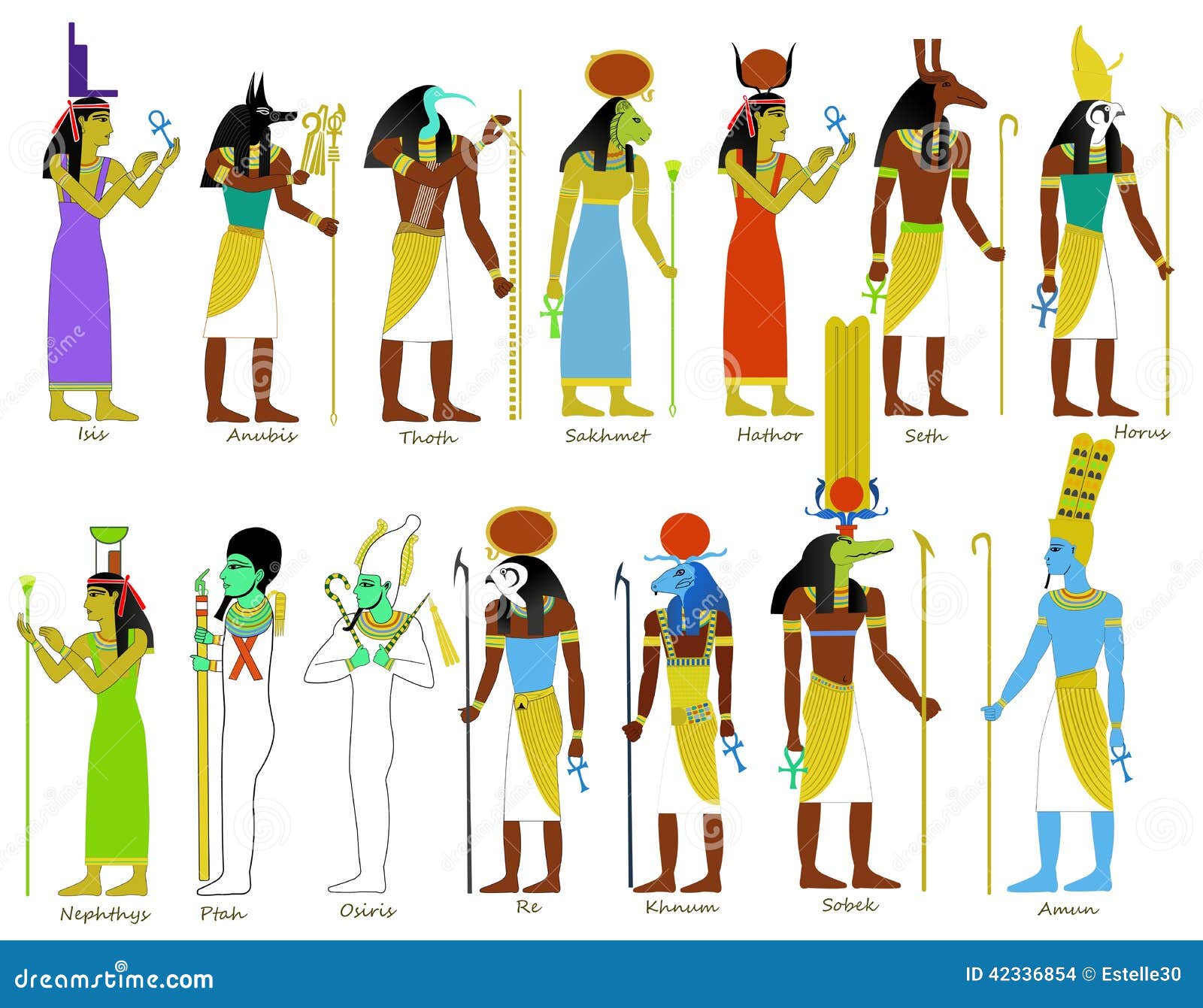

Walk into any major museum—the Met, the British Museum, the Louvre—and you’ll see them. Those stiff, colorful, and frankly bizarre images of ancient Egyptian gods staring back at you with animal heads and unblinking eyes. It’s easy to think the Egyptians were just obsessed with furries or had a limited grasp of perspective. They didn't.

Actually, the way these deities were depicted was a highly sophisticated language. Every curve of a beak and every tint of skin pigment was a calculated choice. If you see a green-skinned man, he isn't sick. He’s Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and that green represents the lush silt of the Nile and the promise of rebirth. It’s basically visual shorthand.

People often ask me why the art feels so "flat." It’s because the Egyptians weren't trying to capture a single moment in time like a snapshot. They were trying to capture the eternal essence of a being. To do that, they showed the most "characteristic" parts of the body. Think about it: a face is easiest to recognize from the side, but an eye is most expressive from the front. So, they just smashed them together. It looks weird to us, but to them, it was the only way to show the "truth" of a person.

The Logic Behind the Animal Heads

Why the animals? This is where most people get tripped up. The Egyptians didn't literally believe their gods were walking around as giant jackals or ibises.

Instead, the animal head served as a name tag. If you saw a figure with the head of a falcon, you knew immediately you were looking at Horus. Why a falcon? Because falcons fly high and have incredible vision, much like a king who needs to watch over his entire domain. It's about the attribute.

Take Anubis. He’s usually shown as a black jackal or a man with a jackal’s head. In the ancient world, jackals were often seen prowling around cemeteries. Instead of just being annoyed by them, the Egyptians flipped the script. They figured, "Hey, if this animal is always hanging around the dead, he must be the one protecting them." So, Anubis became the guardian of the mummification process. His skin is black in these images of ancient Egyptian gods because black was the color of the fertile Nile soil—symbolizing regeneration—and also the color of a body after it had been treated with resin during embalming.

Not All Gods Stayed the Same

The imagery was fluid. Religion in Egypt lasted for over 3,000 years. Things change!

🔗 Read more: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

Thoth is a great example. Sometimes he’s a baboon, and sometimes he’s an ibis. Why the switch? Baboons are noisy and smart, which fits the god of wisdom, but the ibis has a curved beak that looks a bit like a crescent moon, and Thoth was also a lunar deity. The artists chose the "costume" that fit the specific function they wanted to highlight in that temple or tomb.

Decoding the Colors in Egyptian Art

Color wasn't just decorative. It was "iwm," which basically translates to "character" or "disposition." If you were painting a god, you didn't just pick a color because it looked pretty on the limestone wall.

- Blue: This was the color of the heavens and the primeval flood. It's why Amun-Ra is often shown with blue skin when he's in his creator form.

- Gold: The Egyptians believed the flesh of the gods was literally made of gold. That’s why the funerary mask of Tutankhamun is so blinding. It wasn't just a flex of wealth; it was a religious necessity to turn the dead king into a god.

- Red: This one is tricky. It symbolized life and fire, but also chaos and the desert. Set, the god of storms and disorder, is frequently associated with red.

If you’re looking at images of ancient Egyptian gods and you see a goddess like Hathor with yellow skin, that’s because yellow was often used to denote women’s skin (since they theoretically stayed indoors) while men were painted a reddish-brown. But with gods, these rules often blurred because they were "luminous" beings.

Perspective and the Hierarchy of Scale

Ever notice how the Pharaoh or a god is five times bigger than everyone else in a painting? That’s not a mistake. It’s called hierarchy of scale.

In the Egyptian worldview, importance equaled size. If you are a puny human making an offering to Isis, you’re going to look like a toddler next to her. This helped the viewer—most of whom were illiterate—understand exactly who was in charge of the scene.

They also used something called "registers." These are the horizontal lines that act like the floor in a comic strip. If a god is floating above a register or placed in a higher one, it usually means they are in a different realm or have a higher status. It’s a very organized way of looking at the universe. Honestly, it’s kind of refreshing compared to the messy, overlapping perspective we use today.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

The "Hidden" Symbolism You Probably Missed

Look at the hands. What are they holding? Usually, it's an Ankh, which looks like a cross with a loop on top. This is the symbol for "life." You’ll often see a god holding it up to a Pharaoh’s nose. They are literally "giving the breath of life."

Then there’s the Was scepter. It’s a long staff with a fork at the bottom and a weird animal head on top. It represents power and dominion. If a god isn't holding one, they're probably not a major player in that specific scene.

The Mystery of the Headgear

The hats are a whole other story.

- The Double Crown: Represents the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

- The Solar Disk: Usually surrounded by a cobra (the uraeus), symbolizing the sun and protection.

- Feathers: Ma'at, the goddess of truth and justice, wears a single ostrich feather. In the afterlife, your heart was weighed against this feather. If your heart was heavier than a bird's plume, you were in big trouble. Specifically, a monster named Ammit (part lion, hippopotamus, and crocodile) would eat your soul.

Why Do These Images Still Haunt Us?

There’s a reason we still put Sekhmet on t-shirts and hang posters of Bastet in our rooms. These images have "ma’at"—a sense of balance and order. Even when they are showing terrifying things, like the weighing of the heart, the lines are clean and the symmetry is calming.

Modern artists like Salvador Dalí and even fashion designers like Alexander McQueen have pulled directly from this visual bank. There is something deeply human about trying to give a face to the forces of nature—the sun, the Nile, death, and birth.

How to View This Art Today (The Right Way)

If you want to actually "read" these images next time you’re at a museum or browsing a digital archive, don't just look at the faces.

📖 Related: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

First, check the feet. Are they both firmly planted, or is one forward? A forward foot usually suggests action or movement. Second, look at the direction the figures are facing. In Egyptian hieroglyphs and art, you usually read "into" the faces of the characters. If the gods are facing right, you read from right to left.

Also, pay attention to the negative space. The Egyptians hated "empty" air. They would fill every square inch with tiny hieroglyphs that act as a caption for the image. These captions often list the god's "titles," like "Lord of Abydos" or "Mistress of the Sycamore."

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you’re genuinely interested in the visual history of these deities, don’t just stick to Google Images.

- Visit the UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. It’s a peer-reviewed resource that goes deep into the "why" behind the art.

- Look for "Ostraca." These are limestone flakes or pottery shards where ancient artists practiced their sketches. They are much more fluid and "human" than the formal temple carvings.

- Check out the Digital Giza project. It’s an incredible 3D resource that lets you see how these images looked in their original architectural context.

The most important thing to remember is that these weren't just "pictures." For the people who made them, these images of ancient Egyptian gods were physical vessels. They believed a piece of the god’s spirit could actually inhabit the statue or the wall painting if the ritual was done correctly. When you look at them, you aren't just looking at art; you're looking at what the Egyptians considered to be a living doorway to the divine.

To get a better handle on this, start by picking one deity—maybe Sobek, the crocodile god—and track how his image changed from the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. You'll see him go from a literal crocodile to a muscular man with a crocodile head, reflecting how the Egyptian relationship with the natural world became more "human-centric" over the millennia.

Stop looking for "beauty" in the Western sense and start looking for "clarity." Once you do that, the logic of the animal heads and the weird perspective finally clicks. It’s not a primitive style; it’s a perfect one.