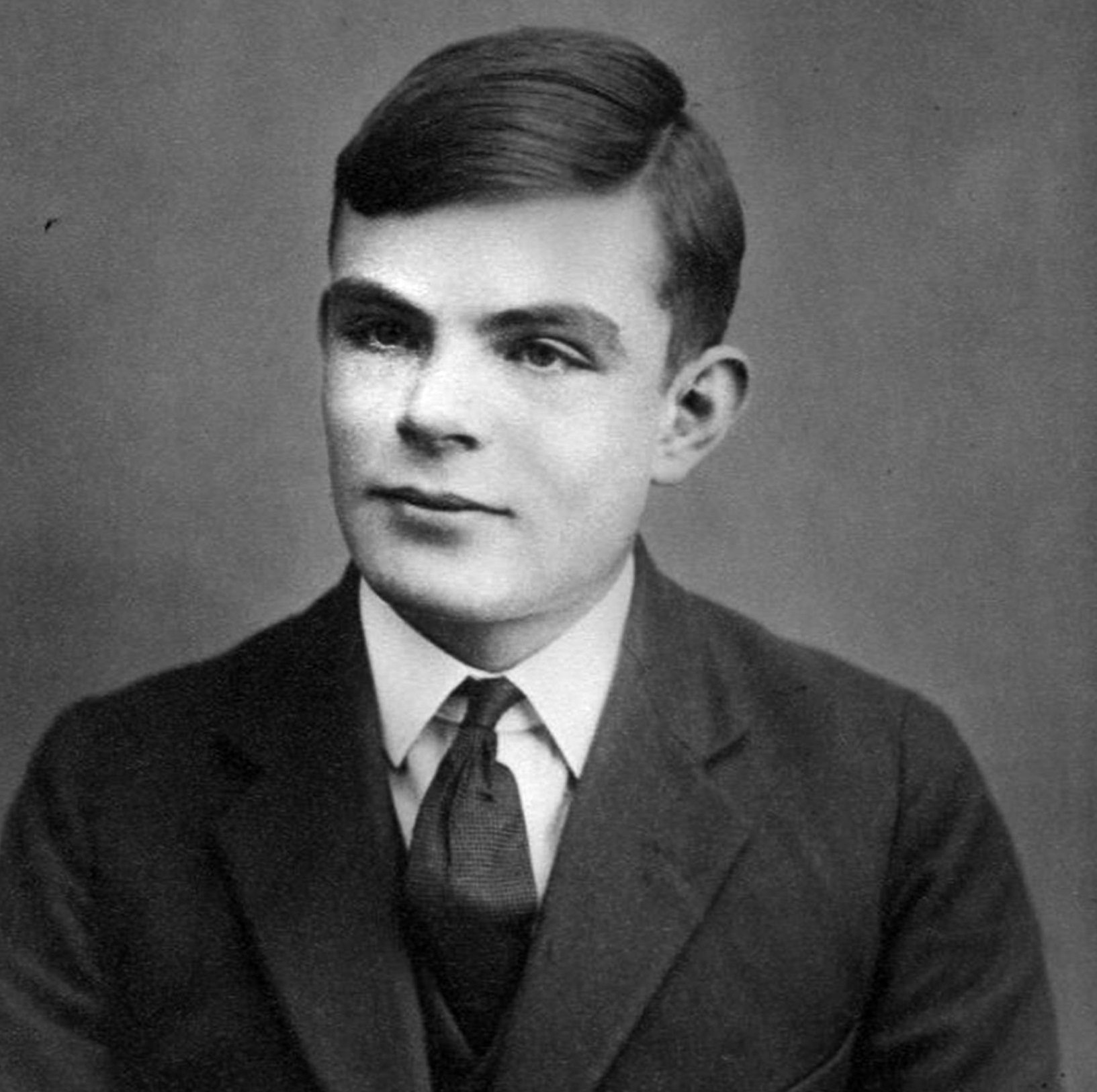

You’ve seen the face. It’s usually that one specific black-and-white portrait where he’s wearing a sensible jacket, looking slightly off-camera with a gaze that feels both distant and incredibly sharp. That’s the 1951 Elliott & Fry photograph. It’s the "official" face of a man who basically invented the future. But if you start digging into the actual archive of images of Alan Turing, you realize how much that single, polished portrait sanitizes the man.

He wasn’t just a static figure in a suit.

There aren’t many photos. Honestly, for someone who changed the course of World War II and laid the groundwork for the laptop or phone you’re using right now, the visual record is surprisingly thin. We have roughly 100 or so distinct photographs, and a huge chunk of them are from his childhood.

The Face of the £50 Note

The most famous of all images of Alan Turing was taken on March 29, 1951. He had just been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. It’s a formal shot. It’s the one you see on the Bank of England £50 note.

But here’s the thing: Turing was notoriously unkempt. His friends at Bletchley Park and later at Manchester University often talked about his "shabby" appearance. He’d use a tie to keep his trousers up. He didn’t care about the social performance of being a "Great Scientist." So, while the 1951 portrait is beautiful, it’s a bit of a lie. It shows the version of Turing that the establishment was finally willing to accept, just a year before they’d prosecute him for being gay.

The Runner in the Scruffy Vest

If you want to see the real Turing, you have to look at the sports photos.

There is one specific image from 1946. He’s finishing a three-mile race in Dorking. He’s thin, almost gaunt, wearing a dark running vest that looks like it’s seen better days. His form is... well, it’s terrible. His arms are held high and awkward. He looks like he’s in pain.

✨ Don't miss: Why April 24 2025 is the Date Everyone in Tech is Watching

This is the man who ran marathons in 2 hours and 46 minutes. That’s an elite time even by today’s standards. He didn’t run for the glory; he told friends he ran to get the "stress" out of his mind. When you look at those images of Alan Turing on the track, you see the raw intensity that drove him to crack the Enigma code. It wasn't just "brain power." it was physical, grinding endurance.

The Missing Bletchley Years

You’d expect hundreds of photos of Turing at Bletchley Park, right? Wrong.

It was a secret intelligence site. Taking a camera to work in 1942 was a great way to get arrested for espionage. Consequently, there are almost zero candid photos of Turing actually working on the Bombe machines or sitting in Hut 8. Most of what we see in documentaries are recreations or photos of the machines themselves.

💡 You might also like: Apple AirTag Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About Tracking

The "Bletchley look" we associate with him—the messy desk, the mug chained to the radiator—comes from written memoirs, not photos. We have to use our imagination to fill in the gaps between the 1930s passport shots and the post-war portraits.

The Childhood Snapshots

A lot of the surviving images of Alan Turing come from his mother, Ethel Sara Turing. She kept everything. There are sketches she made of him at Hazelhurst Preparatory School in 1923. One is titled "Hockey or Watching the Daisies Grow." It’s a perfect encapsulation of his personality: a boy supposed to be playing a team sport but instead getting distracted by the mathematical patterns of nature.

Then there’s the 1928 portrait from Sherborne School. He’s 16. You can already see the defiance in his eyes. He hated the rigid, classical education of British public schools. He wanted to do chemistry and math; they wanted him to write Latin verses.

Why Authenticity Matters Now

In the age of AI-generated art, "fake" images of Alan Turing are everywhere. You’ll see "colorized" versions that make him look like a Hollywood star (often leaning too hard into the Benedict Cumberbatch likeness).

Stick to the archives. The King’s College Turing Archive in Cambridge is the gold standard. They hold the physical prints that his family donated. When you look at an authentic, grainy, slightly out-of-focus photo of Turing, you’re seeing the actual light that bounced off a man who was once a "living ghost" of the British intelligence service.

How to Find High-Quality Archival Images

If you are looking for authentic visuals for a project or just out of curiosity, don't just grab the first thing on Google Images.

- The Turing Digital Archive: Hosted by King’s College, Cambridge. It’s free and contains thousands of scanned documents and photos.

- The National Portrait Gallery (London): They hold the original Elliott & Fry negatives.

- Bletchley Park Trust: Good for photos of the environment he worked in, even if Alan isn't in every frame.

Stop looking for the "perfect" photo. The beauty of Turing's legacy is in the cracks—the messy hair in his 1936 Princeton ID, the strained expression on the finish line, and the quiet, almost shy smile in the few snapshots we have from his time in Manchester. Those are the images that tell the story of a human being, not just a historical icon.

To get a true sense of his life, start by comparing the 1951 Royal Society portrait with the 1946 Walton Athletics Club photo. The contrast between the "established scientist" and the "obsessive runner" is where the real Alan Turing lives. Seek out the scans provided directly by the King's College Archive to ensure you're viewing unedited historical records rather than AI-enhanced modern interpretations.