Africa is huge. You know that, right? But looking at most images of a map of africa found on classroom walls or digital clip art, you’d never guess just how massive the continent actually is. Most people grew up staring at the Mercator projection. It's that classic rectangular map from 1569. It was great for sailors because it preserved straight lines for navigation, but it absolutely trashes the scale of landmasses near the equator.

On a standard Mercator map, Greenland looks roughly the same size as Africa. Honestly, it’s a joke. In reality, Africa is about fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the United States, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe inside the African borders and still have room for a coffee break.

The Mercator Mess and Why Projections Matter

We have a hard time wrapping our heads around 3D spheres turning into 2D rectangles. It’s mathematically impossible to flatten a globe without stretching something. Most digital images of a map of africa still default to this distorted view. This isn't just a "fun fact" for geography nerds; it shapes how we perceive the importance of entire nations. When a continent is shrunk down visually, it’s easier for the subconscious to dismiss its geopolitical weight.

Cartographers like Arno Peters tried to fix this. The Gall-Peters projection gained fame in the 1970s for showing the "correct" size of continents. If you look at a Gall-Peters map, Africa looks like a long, stretched-out teardrop. It’s jarring. People hate it because it looks "wrong" to their eyes, even though the area scale is much more accurate. Then there’s the Robinson projection or the Winkel Tripel—which National Geographic uses—that tries to find a middle ground by curving the edges.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Modern Satellite Imagery

If you hop onto Google Earth or look at high-resolution satellite images of a map of africa, the colors tell a story that political lines miss. It’s not just one big jungle. It’s not one big desert. The Sahara is a massive, beige scar across the top third, but then you hit the Sahel—a transition zone that is currently the focus of the "Great Green Wall" project.

👉 See also: Full Moon San Diego CA: Why You’re Looking at the Wrong Spots

The Great Green Wall is a real, massive undertaking involving over 20 countries. They are trying to plant a 5,000-mile long line of trees to stop the desert from creeping south. When you look at infrared or "normalized difference vegetation index" (NDVI) maps, you can see the pulse of the continent. The green moves up and down depending on the rains. It’s like the continent is breathing.

The Political Border Problem

Maps are lies. Not always malicious lies, but they are simplifications. The borders you see on a political map of Africa were largely drawn during the Berlin Conference of 1884. European powers sat in a room with a map and a ruler. They didn't care about ethnic lines, watersheds, or historical kingdoms.

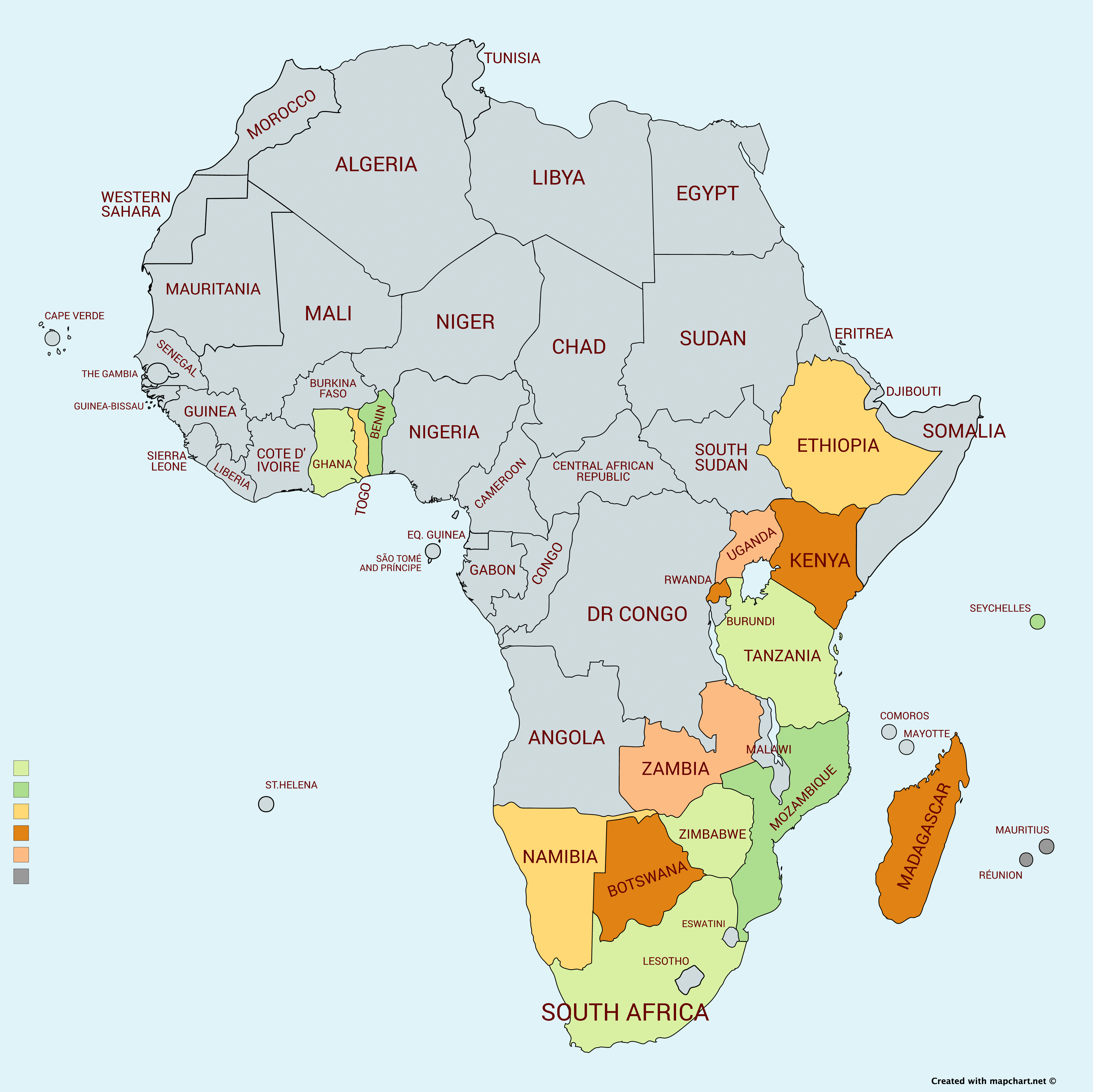

Because of this, modern images of a map of africa often hide the internal complexity. If you look at an ethno-linguistic map instead of a political one, the continent explodes into thousands of distinct regions. Nigeria alone has over 500 languages. When we look at a single silhouette of the continent, we’re missing the fact that it’s 54 different countries with wildly different economies, tech scenes, and landscapes.

Digital Cartography and the Tech Boom

Lately, the way we consume images of a map of africa has shifted toward data visualization. Fiber optic undersea cables are a great example. If you look at a map of Africa’s internet infrastructure, you see these massive lines hugging the coast, connecting hubs like Lagos, Nairobi, and Cape Town to the rest of the world.

✨ Don't miss: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

There's also the "Night Lights" data from NASA. These images show where the power is. You see the Nile River lit up like a glowing serpent. You see the dense clusters around Johannesburg. But you also see vast areas of darkness. This isn't just "empty" space; it’s a representation of the urban-rural divide and the massive potential for off-grid solar energy, which is currently exploding in East Africa.

Misconceptions Found in Popular Stock Photos

Go to any stock photo site and search for a map of the continent. You'll see a lot of "tribal" textures or sunsets with acacia trees superimposed over the shape of the land. It’s a trope. It's the "Lion King" version of geography.

Real experts look at topographical maps. The East African Rift is a massive geological tear where the continent is literally pulling itself apart. One day, millions of years from now, a new ocean will form there. If you look at a relief map, you can see the Ethiopian Highlands—the "Roof of Africa"—which stay cool and lush while the surrounding lowlands bake. This elevation is why Ethiopia is one of the world's top coffee producers. Geography dictates destiny.

Using Interactive Maps for Real Insight

If you actually want to understand the scale, stop looking at static pictures. Use "The True Size Of" tool. It’s a web app that lets you drag countries around a map. If you slide the United Kingdom over Madagascar, you’ll see they are surprisingly similar in size. If you drag the US over North Africa, it barely covers the Sahara.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

We also have to talk about "Upside Down" maps. In space, there is no "up." South-up maps are perfectly valid, and they completely change your perspective on Africa's position in the world. Suddenly, it’s not "down there" at the bottom of the map; it’s at the top, looming over Europe. It’s a simple flip, but it breaks the mental bias we've had since elementary school.

Practical Steps for Finding Accurate Visuals

If you need images of a map of africa for a project, a presentation, or just to satisfy your own curiosity, don't just grab the first thing on a search engine.

- Check the projection. If it's a rectangle and Greenland is huge, it's a Mercator map. Use it for navigation, but don't use it to judge size. Look for "Equal Area" projections for accuracy.

- Seek out thematic maps. Don't just look at borders. Look at population density maps, topographic reliefs, or climate zone maps (Köppen-Geiger scale).

- Use OpenStreetMap. It’s the "Wikipedia of maps." Because it’s community-driven, it often has better data for African cities than Google Maps does, especially in rapidly growing informal settlements.

- Follow the African Remote Sensing & Cartography associations. Groups like the African Association of Remote Sensing of the Environment (AARSE) provide data that is actually gathered and verified by people on the ground, not just satellites from thousands of miles away.

The continent is too big and too varied to be captured by a single silhouette. Whether you're looking at the tech hubs of Rwanda or the dunes of Namibia, the map is only the beginning of the story. Stop trusting the Mercator distortion. Start looking at the data that shows the true, massive scale of the African landmass. It changes how you see the world.

Think about the mineral maps. The sheer concentration of cobalt, gold, and lithium across the "Copperbelt" in DRC and Zambia is what powers your phone and your electric car. When you see a map that highlights these resources, you realize Africa isn't on the periphery of the global economy—it's the engine room. Every time you see a map, ask yourself who drew it and what they were trying to prove. Accurate geography is the first step toward accurate history.