You’re staring at a grainy, black-and-white screen in a cold exam room. The doctor points to a thin, jagged line that looks like a hair on the lens, but it’s not. It’s your fibula. Or maybe your tibia. Honestly, looking at images of a fractured ankle for the first time is overwhelming because, unless you’re an orthopedic surgeon, it just looks like a mess of grey shadows and white shapes. You want to know how bad it is. You want to know if you need a plate and six screws or if you can just get away with a velcro boot and some Netflix time.

It’s broken.

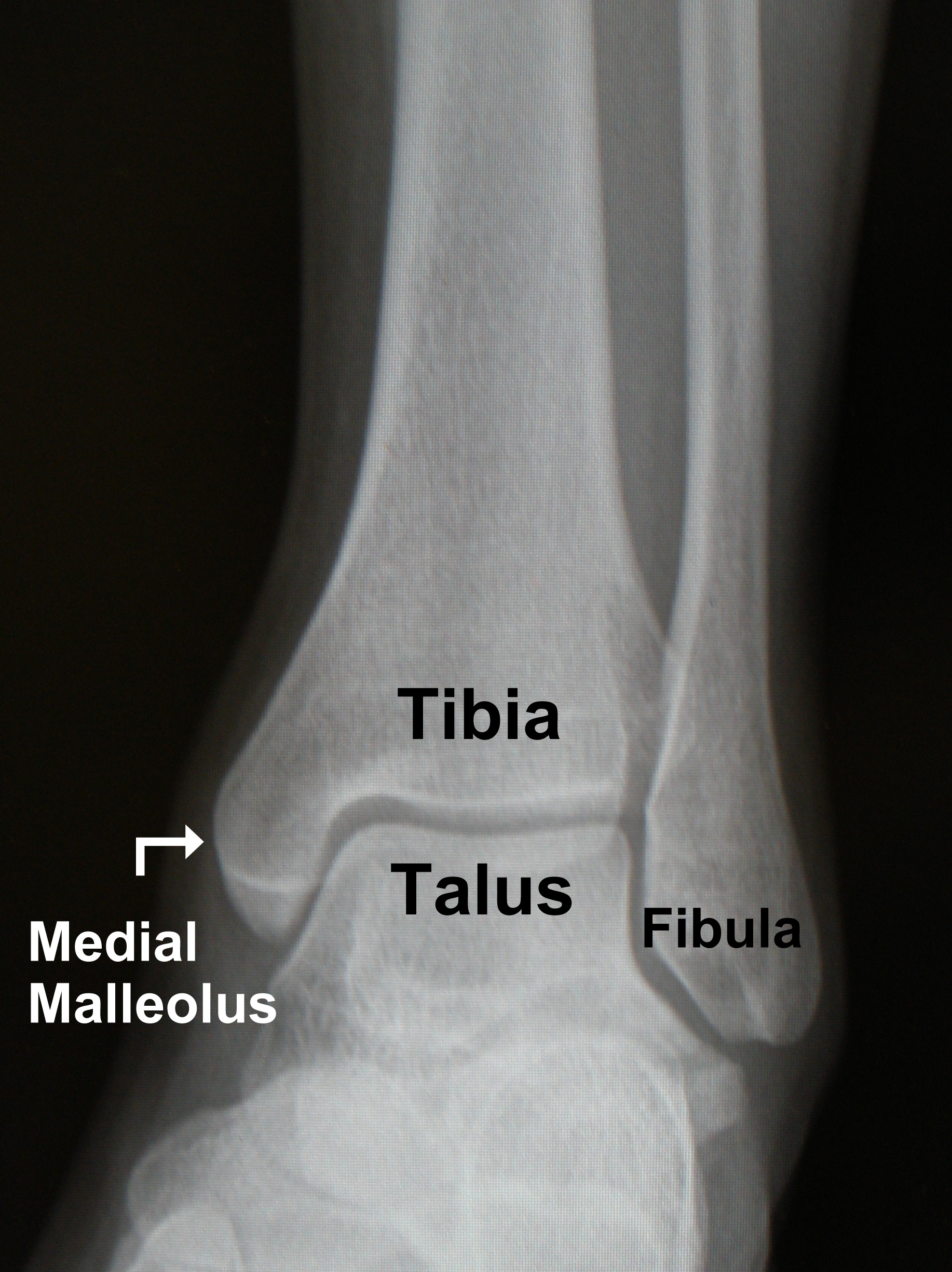

The anatomy of the ankle is surprisingly crowded. You’ve got the talus sitting right in the middle, acting like a hinge, while the tibia (shin bone) and fibula (that thin outer bone) create a sort of bracket around it. When you see a "clean" break on a radiograph, the lines are sharp. But when things get complicated—like in a trimalleolar fracture—the images start to look like a puzzle that someone dropped on the floor.

Why Some Breaks Look Worse Than They Are

A common misconception is that a "shattered" bone is always the worst-case scenario. While it’s definitely not good, sometimes a simple-looking displacement is actually trickier for a surgeon to fix. If the "mortise"—that’s the U-shape where your leg bones meet your foot—is widened by even a few millimeters, your long-term stability is at risk. On an X-ray, this looks like a tiny gap. In real life, it’s the difference between walking normally in six months or developing arthritis by the time you're forty.

Doctors look for "clear space." If that dark gap between the bones is too wide, it means the ligaments are likely shredded. You can't always see ligaments on a standard X-ray. That’s why your doctor might look at images of a fractured ankle and then immediately order an MRI. The X-ray shows the "bricks," but the MRI shows the "mortar."

👉 See also: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

The Weber Classification Reality

Surgeons don't just say "it's broken." They use the Danis-Weber scale. It’s basically a way to categorize where the fibula snapped in relation to the joint line.

Type A is below the joint. Usually stable. You might just get a cast.

Type B is at the level of the joint. This is the "maybe" zone for surgery.

Type C? That’s way above the joint. If you see a break high up on the calf in your images of a fractured ankle, it’s almost certainly a surgical case because it means the syndesmosis—the membrane holding your two leg bones together—has been torn apart.

Reading the Shadows: Displacement vs. Angulation

When you're looking at your own films, pay attention to two things: displacement and angulation. Displacement is how far the bone pieces have shifted away from each other. If they’re 100% displaced, they aren't even touching anymore. Angulation is the angle. If your bone looks like a boomerang, you’re in for a long recovery.

I’ve seen patients get terrified by "avulsion fractures." These look like a tiny flake of bone just floating there. It looks like nothing. But that flake was actually ripped off by a ligament. Sometimes, the "tiny" break is actually more painful than a clean snap because the soft tissue damage is so extensive.

✨ Don't miss: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

Then there are the "hidden" fractures. Stress fractures often don't even show up on initial images of a fractured ankle. You could be in agony, get an X-ray, and the doctor says, "Looks fine." Two weeks later, once the bone starts trying to heal, a cloudy white area called "callus" appears on the image. That's the bone's version of a scab. Only then is the fracture "visible."

What Surgery Looks Like on Film

If you end up with "hardware," your future X-rays are going to look like a trip to the Home Depot. You'll see stainless steel or titanium plates and screws. They show up as bright, solid white because metal is much denser than bone.

Sometimes you’ll see a "syndesmotic screw." This is a long screw that goes through both the fibula and the tibia to hold them together while the ligaments heal. It’s a temporary fix, often removed later so the bones can move naturally again. If you see this in your images of a fractured ankle, know that your mobility will be strictly limited for a while. You cannot put weight on that screw, or it will snap like a twig.

The Complications You Can Actually See

Post-traumatic arthritis is the big boogeyman. In a healthy ankle image, there’s a nice, even space between the talus and the tibia. That’s your cartilage. Since cartilage is invisible on X-rays, we judge its health by the "joint space." If the bones are touching (bone-on-bone), the cartilage is gone.

🔗 Read more: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

You might also see "osteophytes." These are bone spurs. They look like little bird beaks poking out from the edges of the bone. They are the body’s way of trying to stabilize a wobbly joint, but they usually just end up hurting.

Actionable Steps for the Newly Injured

If you are currently looking at images of a fractured ankle or waiting for your results, here is exactly what you need to do to ensure the best recovery.

- Ask for the "Lateral" and "AP" views. Don't just look at one angle. A break can look perfectly aligned from the front but be totally tilted from the side. You need the full 3D picture.

- Request a digital copy. Most clinics provide a CD or a portal link. Keep this. If you ever need a second opinion or see a physical therapist, having the original baseline images is vital for tracking bone Union (healing).

- Look for the "Fat Pad Sign." If you see a dark, sail-shaped shadow near the joint, that’s swelling pushing the fat out of the way. It’s a tell-tale sign of an internal fracture even if the bone line isn't obvious yet.

- Don't Google "worst-case scenarios." Every ankle is different. A professional athlete's fracture image might look horrific, but they have access to 24/7 rehab. Your recovery depends on your biology, your surgeon’s skill, and your dedication to physical therapy.

- Verify the "Mortise View." Ask your tech if they took a mortise view. This is where they turn your foot slightly inward (about 15 degrees) to get the clearest look at the joint space. It’s the gold standard for spotting instability.

Healing takes time. Bone usually takes 6 to 8 weeks to knit back together, but the remodeling process—where the bone gets its strength back—can take a year. Your future images of a fractured ankle will show that jagged line slowly blurring and fading until it's just a faint memory on a screen. Listen to the radiologists, but more importantly, listen to your body. If the image looks "healed" but it still hurts to walk, the soft tissue likely needs more work.

The image is just a snapshot. Your recovery is the whole movie.