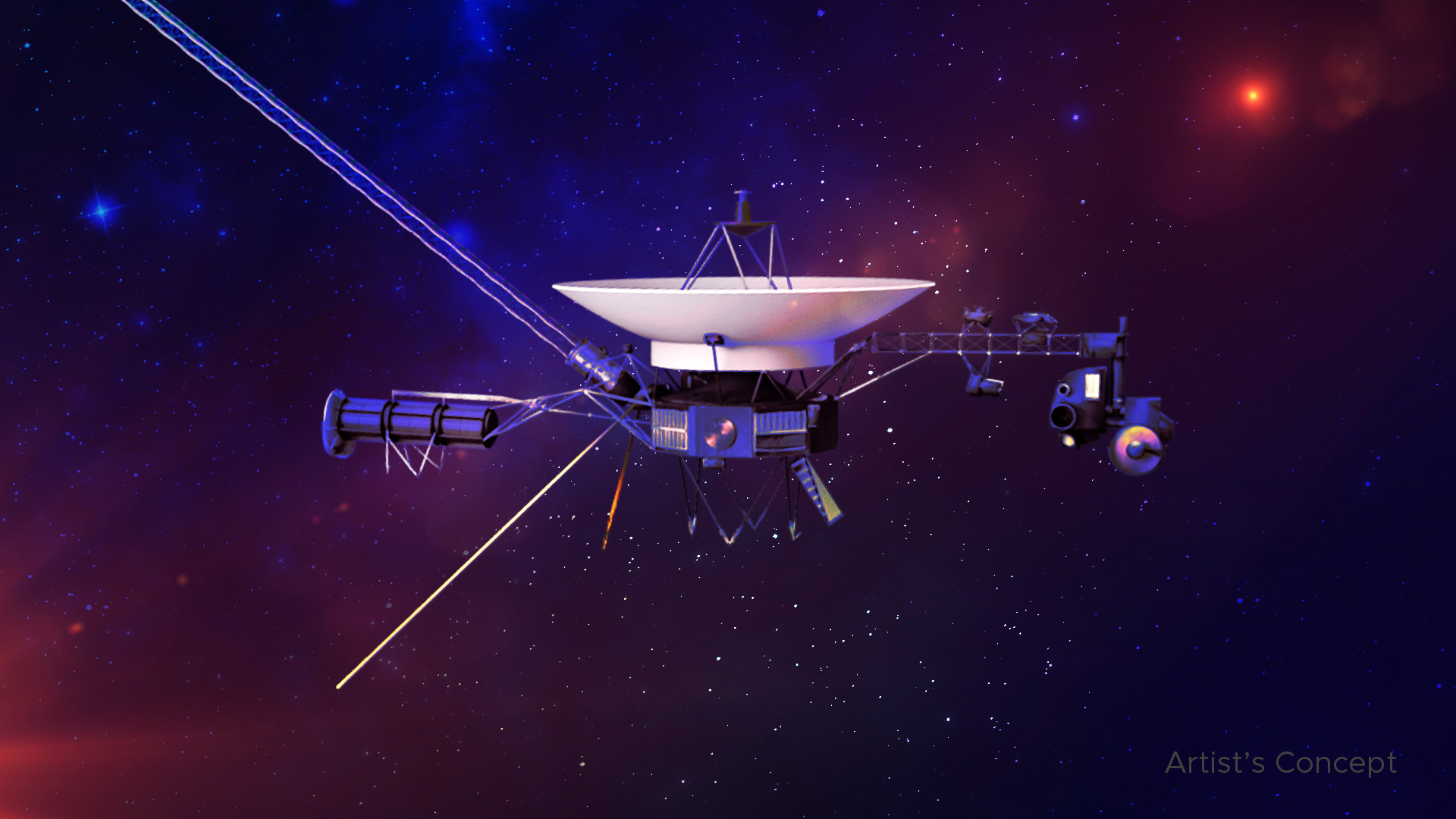

It is weird to think about a piece of technology launched in 1977 still being the benchmark for how we "see" the edge of our solar system. Voyager 1 is basically a flying fossil. It has less computing power than the key fob you use to unlock your car, yet the images from Voyager 1 remain some of the most emotionally charged visuals in human history. They aren't high-definition. They aren't color-corrected by a social media algorithm. They are raw, noisy, and absolutely terrifying when you really stop to think about the scale they represent.

Space is big. Really big.

When Voyager 1 launched from Cape Canaveral on September 5, 1977, the goal was ambitious but relatively straightforward: go look at Jupiter and Saturn. Nobody really knew if the cameras would survive the intense radiation belts of Jupiter. The scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) were essentially "flying blind" into environments that had only been theorized. What they got back changed everything.

The day Jupiter became a real place

Before we had the high-resolution images from Voyager 1, Jupiter was mostly a blurry tan marble in even the best Earth-based telescopes. Then came 1979. As the probe screamed toward the gas giant, the detail started to resolve. We saw the Great Red Spot not as a static "eye," but as a churning, chaotic hurricane larger than our entire planet.

It wasn’t just the planet, though. It was the moons.

Io was the biggest shock. Before Voyager, people thought moons were supposed to be dead, cratered rocks like our own. Instead, the images showed a pizza-colored world covered in active volcanoes. Linda Morabito, an optical navigation engineer at JPL, was the one who spotted the plume. It was the first time we’d ever seen active volcanism on another world. It changed the way we thought about tidal heating and the potential for energy—and maybe life—in the outer solar system.

Saturn and the art of the rings

By the time the craft reached Saturn in 1980, the world was hooked. The rings weren’t just solid bands. They were thousands of individual "ringlets" made of ice and rock, dancing in a complex gravitational ballet.

👉 See also: What Is Hack Meaning? Why the Internet Keeps Changing the Definition

But there’s a specific shot that people always overlook. It’s the "backlit" view of Saturn. Voyager 1 moved behind the planet and looked back toward the Sun. The rings glowed. It looked like a neon sign in the middle of a dark ocean. This wasn't just data collection; it was accidental art. Honestly, the graininess of the 800x800 pixel Vidicon cameras gives these shots a gritty, cinematic quality that modern digital sensors sometimes lack. They feel "earned."

The Pale Blue Dot: A perspective shift

You can't talk about images from Voyager 1 without talking about February 14, 1990. This was the "Family Portrait" sequence. Carl Sagan had to beg NASA to turn the cameras around one last time. Engineers were worried. Pointing the camera so close to the Sun could fry the sensors. Plus, there wasn't much "science" to be gained from looking backward.

Sagan won.

From 3.7 billion miles away, Voyager 1 snapped a series of photos. In one of them, tucked inside a scattered beam of sunlight, is a tiny, flickering speck. That’s us. That’s Earth. It’s less than a pixel wide.

That single image did more for environmentalism and global perspective than a thousand speeches. It showed us as we are: lonely. We’re a "mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam." If you ever feel like your problems are too big, go look at that photo. It’s a literal reality check.

Why we stopped taking pictures

People often ask why we don't have recent images from Voyager 1 showing what the interstellar medium looks like. The answer is kinda depressing but practical.

✨ Don't miss: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

- Power: The Plutonium-238 in the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) is decaying. Every year, the probe loses about 4 watts of power.

- Bandwidth: At its current distance—over 15 billion miles away—the data rate is abysmally slow.

- The Cameras are Off: To save power for the instruments that measure magnetic fields and plasma, NASA turned off the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) back in 1990.

The cameras are literally cold and dead now. Voyager 1 is currently flying through the "soup" between stars, but it’s doing it in total darkness. It is sensing the universe through touch (particles) and sound (vibrations in plasma) rather than sight.

The tech behind the magic

It’s easy to forget that these photos were taken using 1970s television technology. These weren't CMOS sensors like in your iPhone. They were vacuum tubes—specifically, Vidicon tubes.

Basically, the light hit a photoconductive surface, and an electron beam scanned it to create an electrical signal. This signal was digitized (slowly) and beamed back to Earth at a rate that would make a 56k modem look like fiber optics. Sometimes it took hours to get a single frame. When the data reached the Deep Space Network (DSN) antennas in places like Goldstone, California, it was just a string of ones and zeros.

The "color" photos you see are actually composites. The probe took three separate black-and-white photos through orange, green, and blue filters. Scientists then layered them back on Earth to recreate what the human eye might see. It was a manual, painstaking process.

The legacy of the "Golden Record"

While not an "image" in the sense of a photograph taken by the probe, the Golden Record is an image on the probe. It contains 116 images encoded in analog form. These shots were meant to explain humanity to whoever (or whatever) might find the craft in a few million years.

There are pictures of:

🔗 Read more: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

- A supermarket.

- The Great Wall of China.

- Anatomy diagrams.

- A woman eating a grape.

- A sunset.

It’s a curated scrapbook of a world that, by the time the record is ever found, will likely be long gone.

What most people get wrong about Voyager's "Photos"

There is a common misconception that the recent "glitches" Voyager 1 experienced in late 2023 and early 2024 were related to the cameras. They weren't. The Flight Data System (FDS) had a corrupted memory chip that prevented the probe from sending back usable data. For months, it was just sending a repeating pattern of gibberish.

The engineers at JPL managed to "hack" a 46-year-old computer from billions of miles away to fix it. That’s the real feat. We aren't getting new images from Voyager 1, but we are getting data about the "hum" of the interstellar vacuum. That is arguably more valuable than another blurry photo of black space.

How to explore the archives yourself

If you want to see the real, unedited data, you don't have to rely on glossy textbook versions. NASA's Planetary Data System (PDS) is a rabbit hole worth falling down.

- Search the OPUS (Outer Planets Unified Search) tool: You can filter by instrument and target planet.

- Look for the "raw" frames: You'll see the static, the missing lines of data, and the "reseau marks" (the little black crosses used for geometric correction).

- Check out the USGS Astrogeology Science Center: They have incredible maps of Jupiter and Saturn’s moons stitched together from these very photos.

The images from Voyager 1 are more than just science. They are a diary of our first real steps away from home. They remind us that for all our noise and fury, we are very small, and the universe is very, very quiet.

To truly appreciate these visuals, don't look at them on a tiny phone screen. Put them on a big monitor, turn off the lights, and realize that the light hitting those sensors traveled for hours across the vacuum of space just so you could see a moon that looks like a pepperoni pizza. It's a miracle it worked at all.

Actionable steps for space enthusiasts

- Download the "Eyes on the Solar System" app: This is a real-time 3D simulation from NASA that lets you "ride along" with Voyager 1 as it exits the solar system.

- Study the "Family Portrait" sequence: Find the full mosaic, not just the Pale Blue Dot. It includes Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. It’s the only time we’ve ever seen our neighborhood from the outside looking in.

- Support the Deep Space Network: The only reason we still "hear" Voyager is because of giant radio dishes on Earth. Read up on the DSN's current upgrades; they are the literal lifeline for our furthest-flung ambassadors.

The cameras are off, but the journey isn't over. Voyager 1 will continue to drift for tens of thousands of years before it gets anywhere near another star. These images are its last testament to where it came from.