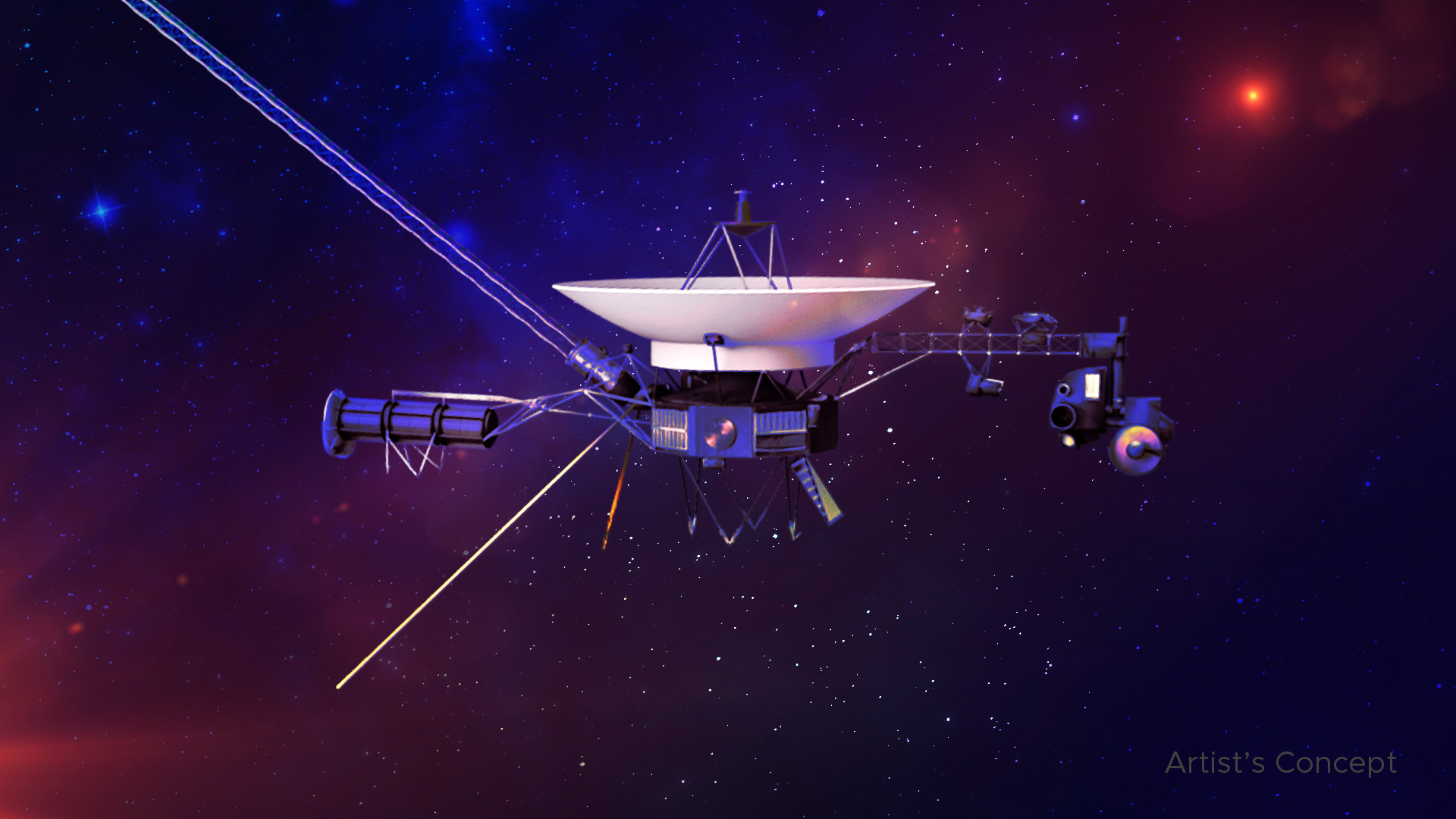

Space is mostly empty, dark, and honestly, a little bit terrifying. But we know what it looks like because of a school-bus-sized machine launched in 1977. When people search for images for Voyager 1, they usually expect high-definition, Hubble-style nebula shots. That’s not what you get. Instead, you get grainy, haunting, and deeply emotional snapshots of a solar system that hadn't been seen up close until the late 70s and 80s.

It’s easy to forget that these photos traveled billions of miles back to Earth using a transmitter that has less power than a lightbulb in your refrigerator.

The Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) on Voyager 1 was a masterpiece of 1970s engineering. It didn't use a digital sensor like your iPhone. It used vidicon cameras—basically modified television tubes. These cameras scanned a scene and converted light into electrical signals that were then digitized into 800 by 800 pixel images. By today's standards, that's tiny. By 1979 standards, it was magic.

The Jupiter Encounter and the Red Spot

When Voyager 1 approached Jupiter in early 1979, the world saw the Great Red Spot for the first time in vivid detail. This wasn't just a red blob. The images for Voyager 1 revealed a churning, violent hurricane larger than Earth itself.

One of the most mind-blowing discoveries came from a navigation image. Linda Morabito, an engineer on the optical navigation team, noticed a strange "bulge" on the limb of the moon Io. Most people might have dismissed it as a glitch or a background star. It wasn't. It was a volcanic plume. Voyager 1 had captured the first evidence of active volcanism on a world other than Earth. This changed planetary science forever. Before this, we thought moons were dead, frozen rocks. Io turned out to be a pizza-colored nightmare of sulfur and lava.

Jupiter’s rings were another shock. We knew Saturn had them, but finding a thin, dusty ring around Jupiter was a curveball. The images were hard to process because the rings were so faint. Scientists had to overexpose the shots, making the planet look like a glowing ghost just to see the dust particles catching the sunlight.

Saturn and the Geometries of Chaos

By 1980, the craft reached Saturn. If you look at the images for Voyager 1 from this era, you’ll notice the rings look like a record groove. Scientists expected a few broad bands of ice and rock. What they got was thousands of thin "ringlets."

👉 See also: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

One of the weirdest things captured was the "spokes" in Saturn's B-ring. These dark, radial features look like the spokes on a bicycle wheel. They shouldn't exist according to simple orbital mechanics. Even today, we’re still debating exactly how they form, though it likely involves electrostatic charges lifting dust above the ring plane.

The cameras also gave us our first real look at Titan. Honestly? It was a bit of a letdown at first. Voyager 1 showed a fuzzy orange ball. Its thick nitrogen atmosphere was impenetrable to the ISS cameras. However, this "failed" image actually spurred the later Cassini-Huygens mission. We needed to know what was under that haze.

The Pale Blue Dot: A Change in Perspective

There is one image that defines the entire mission. In 1990, after Voyager 1 had finished its primary mission, Carl Sagan convinced NASA to turn the camera around one last time.

The spacecraft was about 3.7 billion miles away.

NASA was actually hesitant to do this. There was a real risk that pointing the camera so close to the Sun could fry the sensitive vidicon tubes. But they took the risk. The result was the "Pale Blue Dot." If you look at this specific set of images for Voyager 1, you can barely see Earth. It’s a single pixel, less than a point of light, caught in a scattered beam of sunlight.

Sagan famously noted that everyone you've ever loved, every king, every peasant, and every conflict happened on that tiny speck. It’s probably the most humbling photograph in human history. It reminds us that in the grand cosmic scale, our drama is microscopic.

✨ Don't miss: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

Shortly after this, the cameras were powered down permanently to save energy for the craft's interstellar instruments. Voyager 1 is still talking to us in 2026, but it’s been blind for over three decades.

How These Images Reach Us

Getting these pictures home isn't like uploading to Instagram.

- Bit Rate: Near Jupiter, Voyager could send data at about 115 kilobits per second. By the time it hit Saturn, that dropped significantly.

- Deep Space Network (DSN): Huge antennas in California, Spain, and Australia have to listen for the faint "whisper" of the spacecraft.

- Digital Construction: The images come down as strings of numbers (0 to 255) representing brightness. Computers then reassemble these numbers into the grids we see.

Sometimes, the data gets corrupted. You’ll see "salt and pepper" noise on old Voyager photos. This is usually caused by cosmic rays hitting the detectors or interference during transmission. Modern restoration experts use AI and sophisticated filtering to clean these up, but the raw files are where the real science lives.

What Most People Get Wrong About Voyager Photos

People often think the colors in images for Voyager 1 are "fake." That's not exactly true, but it's not simple either. The cameras took black-and-white photos through different colored filters—red, green, and blue. To get a color image, scientists have to stack these three separate frames on top of each other.

Sometimes, they use "false color" to highlight specific things, like methane clouds or temperature differences. If you see a neon-purple Saturn, that’s a scientist trying to show you chemical composition, not what you'd see if you were standing on the bridge of the Enterprise.

Another misconception is that Voyager 1 is currently taking pictures of other stars. It isn't. As mentioned, the cameras are off. The power levels are too low to run them, and even if they were on, there's nothing nearby to photograph. It's moving through the "Local Fluff," a region of interstellar space, and it won't pass near another star for about 40,000 years.

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Digital Face: Why Your Screen Layout Is Probably Killing Your Battery (And How To Fix It)

How to Find and Use High-Res Voyager Data

If you’re looking for the best quality images for Voyager 1, don’t just use a generic search engine. Go to the source. The Planetary Data System (PDS) maintained by NASA is the repository for every raw bit sent back.

- Visit the NASA Photojournal website. It’s the easiest way to find curated, high-quality versions of these shots.

- Check out the JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) Voyager galleries. They have the "greatest hits" with detailed captions explaining exactly what you're looking at.

- Look for "Calibrated" vs "Raw" images. Calibrated images have been corrected for camera distortions, making them much better for desktop wallpapers or printing.

For the true nerds, there are community-driven projects like https://www.google.com/search?q=UnmannedSpaceflight.com where enthusiasts use modern software to re-process 40-year-old data. They often produce images that look better than what NASA released in the 80s because they have much more processing power at their disposal.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to do more than just look at a screen, you can actually interact with this history.

First, download the NASA Eyes on the Solar System app. It’s a real-time 3D simulation. You can "ride along" with Voyager 1 and see exactly where it is pointing right now, even though the cameras are off. It gives you a sense of the sheer scale of the distance.

Second, if you're a teacher or a creator, look for the Voyager Golden Record images. Along with the photos the craft took, it carries 116 images of Earth encoded on a gold-plated copper record. These were chosen by a committee led by Frank Drake and Carl Sagan to explain humanity to any aliens who might find the craft in a few million years. They include diagrams of DNA, photos of people eating, and maps of our solar system.

Finally, keep an eye on the Deep Space Network Now website. It’s a live dashboard showing which spacecraft are currently talking to Earth. Every once in a while, you’ll see "VGR1" pop up. Even without new photos, seeing that "carrier signal" from 15 billion miles away is a profound experience. It’s a tether to a machine that has become our furthest-flung ambassador.

Voyager 1 is running out of juice. By 2030, it’s likely that all the instruments will be off. It will become a silent monument, drifting forever. But the images it left behind remain some of the most important documents in the history of our species. They turned dots of light into real places.