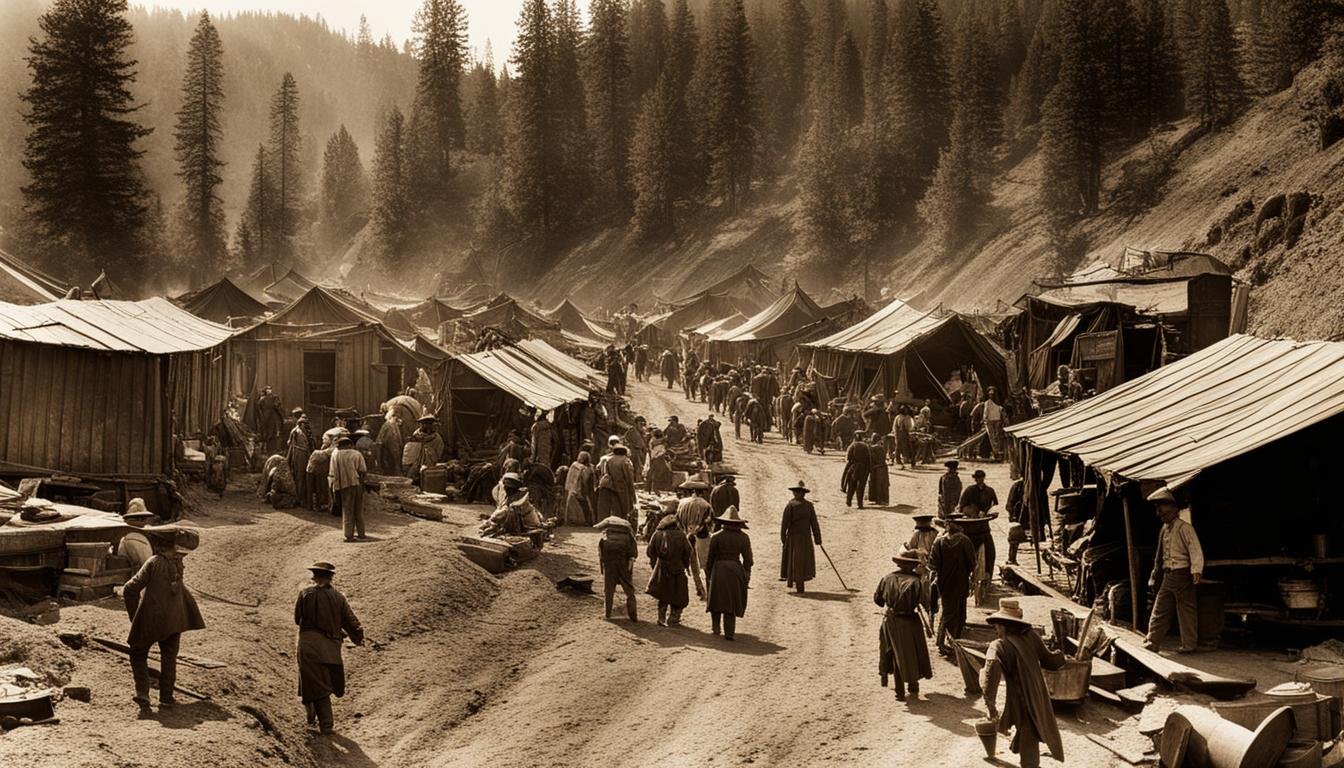

If you close your eyes and think about the 1840s, you probably see grainy, sepia-toned ghosts staring blankly into a camera lens. It’s easy to think of that era as a quiet, slow-moving time. But then you look at the images California gold rush era left behind, and everything changes. You see the mud. You see the sheer, desperate exhaustion in a teenager’s eyes. You see the way they literally moved mountains with nothing but high-pressure water and a lack of concern for the future.

The gold rush wasn't just a move; it was a fever. It was a massive, global hallucination that California was paved with literal yellow bricks. When James W. Marshall found those first flakes at Sutter’s Mill in early 1848, there wasn't a photographer for miles. But by 1849, the world had caught wind, and the daguerreotype—the first commercially successful photographic process—was there to capture the mess.

Honestly, these photos are kind of a miracle. Taking a picture in 1850 wasn't like pulling out an iPhone. You had to coat a silvered copper plate with chemicals, expose it for what felt like forever, and then develop it with mercury vapor. Yes, mercury. People were literally poisoning themselves to capture a shot of a guy holding a shovel.

Why the Images California Gold Rush Photographers Left Behind Are So Gritty

Most of the "official" art from the time consists of romanticized oil paintings. They show heroic men standing on clean rocks. Real photography tells a different story. If you look at the daguerreotypes held by the Library of Congress or the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, the first thing you notice is the environmental destruction.

California was beautiful, then it wasn't.

Hydraulic mining was the culprit. Miners realized that instead of panning in a cold creek, they could just blast the side of a hill with a massive water cannon called a "monitor." The images California gold rush archives show these monitors in action, and it looks like a war zone. Entire hillsides were liquidated into sludge. This wasn't "man in harmony with nature." This was "man destroying nature for a paycheck."

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The people in these photos look older than they are. You’ll see a photo of a "forty-niner" who looks sixty, but the archives tell us he’s actually twenty-four. That’s what sleeping in a tent and eating salt pork does to a person. They weren't all white Americans, either. That’s a huge misconception. The photography shows Chinese miners, Mexican "gambusinos," and African American men who had traveled thousands of miles for a shot at freedom or fortune.

The Daguerreotype: A Mirror with a Memory

Each of these early images is a one-off. There was no negative. If you owned a daguerreotype of yourself at the diggings, you owned the only copy in existence. It’s why so many miners sent them home to families in the East or in Europe. "Look, I’m still alive," the photo whispered.

Wait. Look closer at the hands in these old photos.

They are often blurred. Why? Because the exposure times were so long that even a slight tremble from a hardworking man's hand would smudge the image. It’s a haunting detail. It shows the physical toll of the labor. You can't fake that kind of fatigue.

The Logistics of the Lens in 1849

Imagine being a photographer like Robert Vance or Carleton Watkins. You couldn't just carry a camera bag. You needed a wagon. You needed a literal rolling laboratory. You had to mix volatile chemicals in a tent while the wind blew dust into your eyes.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Watkins is a legend for a reason. He eventually moved to giant "mammoth plates" to capture the scale of Yosemite and the mining camps. When people in New York saw his images California gold rush prints, they couldn't believe the scale. It helped lead to the very idea of national parks, strangely enough. People realized that if they didn't protect the land, the miners would wash it all into the Pacific.

Beyond the Pan: What the Pictures Don't Show

Photos of the era are selective. You see the "successful" miners posing with their gear. You rarely see the thousands who died of cholera on the way out. You don't see the thousands who ended up working as waiters in San Francisco because they never found a single grain of gold.

San Francisco itself was a photographic marvel. In 1848, it was a tiny hamlet. By 1850, it was a sprawling, chaotic metropolis of tents and wood shacks. There is a famous panoramic series of daguerreotypes from 1851 showing the harbor choked with abandoned ships. The crews had literally jumped overboard to run to the hills. Those ships were eventually used as floating warehouses, hotels, and even jails before being built over. Today, those ships are still buried under the Financial District.

The diversity is the real kicker. While the "Foreign Miners Tax" of 1850 tried to push out non-Americans, the photos prove how international the scene remained. You see Peruvian miners and Frenchmen. You see the tension. Nobody is smiling in these photos. Partly because of the long exposure, but mostly because life was incredibly hard.

The Cost of a Portrait

Getting your picture taken in a mining camp was a luxury. It might cost a few dollars in gold dust—a fortune back then. But for a man who might die of a cave-in or scurvy next week, it was the only way to ensure he wasn't forgotten. These were the first "selfies" of the industrial age, and they were fueled by the fear of anonymity.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

How to Spot a Fake Gold Rush Photo

With the rise of AI and high-quality "vintage" filters, people get fooled a lot lately. Real images California gold rush era photos have very specific markers:

- The Case: Authentic daguerreotypes are almost always in small, ornate leather or "thermoplastic" cases.

- The Reflection: A real daguerreotype looks like a mirror. If you tilt it, the image flips from positive to negative.

- The Background: Look for authentic 1850s tools. Long-handled shovels, rockers, and "long tom" sluices. If the gear looks like something from a 1950s Western movie, it’s probably a recreation.

- The Clothing: Miners didn't wear cowboy hats. Most wore wide-brimmed felt hats or flat caps. Their clothes were heavy wool and canvas, usually filthy.

The Environmental Legacy Captured on Film

By the 1860s and 70s, as photography improved, the scale of "Hydraulic Mining" became the primary subject. These aren't just photos; they are evidence. They were used in court cases like Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Co., which was one of the first major environmental rulings in U.S. history. The photos showed how the debris was choking the rivers and flooding farms in the valley.

In a way, photographers were the first whistleblowers. They didn't just capture "pretty" scenes; they documented the violent birth of modern California.

Finding These Images Today

If you want to see the real deal, don't just search social media. Go to the source. The California Historical Society has an incredible digital collection. So does the J. Paul Getty Museum.

When you look at these files, zoom in. Look at the mud on their boots. Look at the way the trees in the background have been stripped of their bark for firewood. It’s a raw, unfiltered look at a time that shaped the world's economy.

The gold rush ended, but the images remain as a reminder of what happens when human greed meets a seemingly limitless wilderness. They are a testament to grit, but also a warning about the cost of progress.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Collectors:

- Verify via Provenance: If you’re looking at purchasing "gold rush" photos, always ask for provenance. Real daguerreotypes from the camps are worth thousands.

- Use Digital Archives: For high-resolution research, use the Calisphere website. It aggregates millions of images from California's top libraries.

- Check the Chemistry: Remember that "tin-types" (ferrotypes) became popular in the mid-1850s and 60s. If the image is on metal but not reflective like a mirror, it’s likely a later era than the initial 1849 rush.

- Visit the Sites: Many of the locations in these famous photos, like Columbia State Historic Park, still have the same buildings. You can literally stand where the photographer stood 175 years ago.

- Study the Tools: Learn to identify a "rocker box" versus a "sluice." Knowing the tech of the time helps you date the photos accurately without needing a historian.