It usually happens at a dinner party or during a casual hang with friends. You reach for that perfect punchline, the one that used to land every single time, and… nothing. Just a dry throat and a room that feels a little too quiet. You walk away thinking, "I'm not funny anymore," and suddenly, it feels like you’ve lost a limb. Humor isn't just about jokes; it’s a social currency. It’s how we connect, how we deflect pain, and how we signal intelligence. When that well runs dry, it’s genuinely terrifying.

You aren't imagining it. Humor isn't a fixed personality trait like your height or your eye color. It is a cognitive function. It requires timing, working memory, and a specific type of emotional bandwidth that isn't always available. If you feel like your wit has evaporated, you’re likely not "boring" now. You’re probably just out of practice, or your brain is busy surviving something else.

The Science of Why the Jokes Stopped

Humor is incredibly expensive for your brain. To be funny, you have to perform a "bisociation"—a term coined by Arthur Koestler in his 1964 book The Act of Creation. This is the ability to hold two self-consistent but incompatible frames of reference in your head at once. When you deliver a punchline, you’re forcing the listener’s brain to jump from one frame to the other. It’s a high-level executive function.

If you’re wondering why "I’m not funny anymore" is your new internal mantra, look at your stress levels. Chronic cortisol elevation is a comedy killer. Research from the Journal of Neuroscience suggests that high stress impairs the prefrontal cortex—the very area responsible for the wordplay and creative leap-frogging required for wit. You can't be Oscar Wilde when your brain is stuck in "fight or flight" mode. When you are worried about rent, your kid's grades, or a looming deadline, your brain reallocates resources. Survival takes priority over satire. Every single time.

💡 You might also like: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

It’s also about "Anhedonia." This is a core symptom of depression where you lose interest in things that used to bring pleasure. But it has a sneaky cousin: social anhedonia. You might still like your friends, but the "play" drive is gone. Humor is, at its heart, a form of play. If the world feels heavy and gray, the cognitive agility needed to find the absurdity in life just feels... heavy. Like trying to run a marathon in work boots.

Life Stages and the Death of "The Bit"

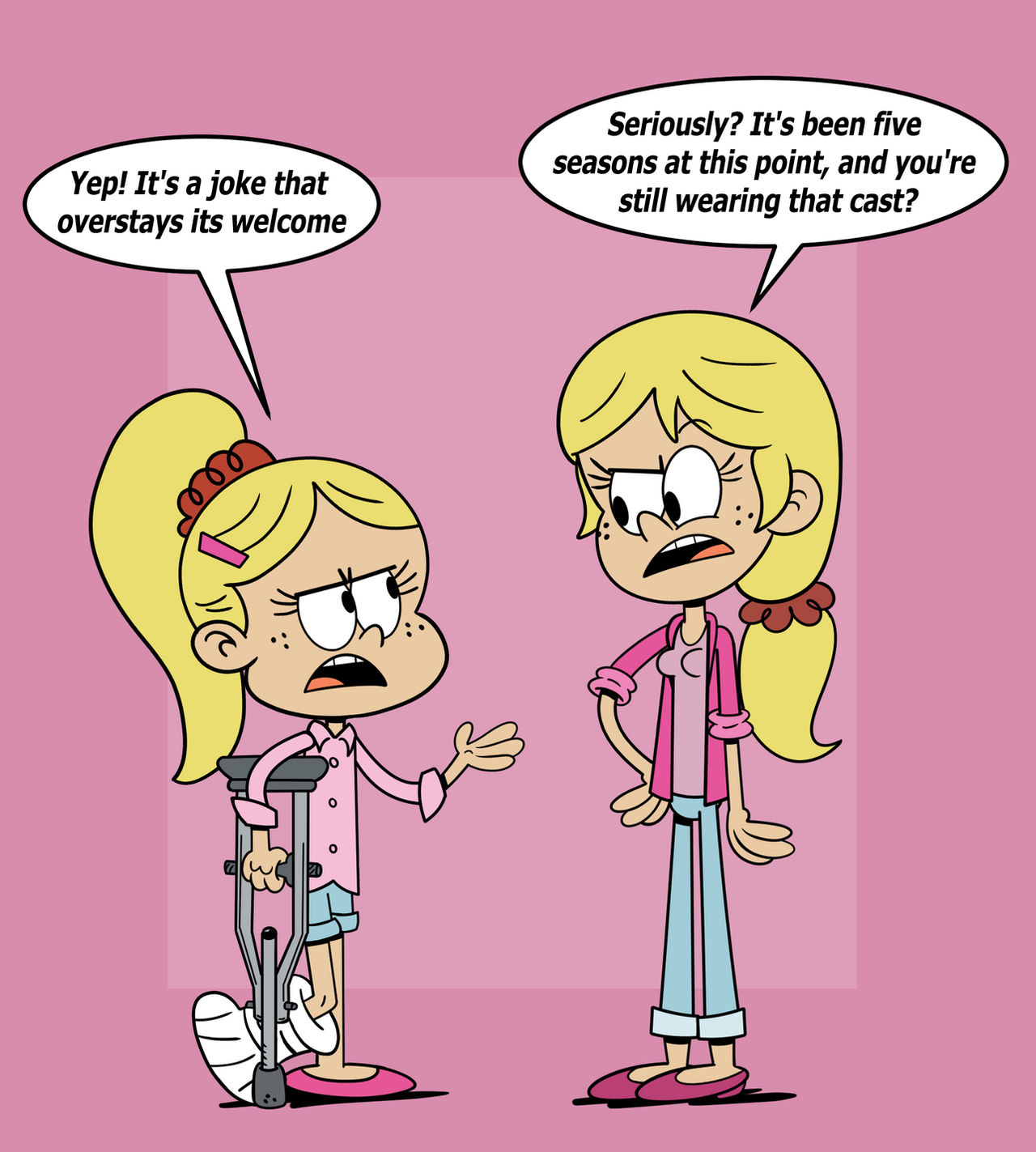

Let’s be honest. Age changes what we find funny, and more importantly, it changes our audience. The "class clown" energy that worked at twenty-two often feels desperate at thirty-five. This shift often leads to a transitional period where people feel they’ve lost their edge. You haven't lost it; you're just outgrowing your old material.

- The Parent Trap: New parents often report feeling like they’ve become humorless. Sleep deprivation is a form of cognitive impairment. It’s hard to be witty when you can’t remember where you put the car keys.

- The Corporate Filter: Years in a professional environment can "sanitize" your brain. You spend eight hours a day monitoring your speech to be HR-compliant. Eventually, that internal censor doesn't turn off at 5:00 PM. You’ve conditioned yourself to be safe, and safety is the enemy of comedy.

- Social Isolation: Humor is a muscle. If you spent the last two years working from home and talking mostly to your cat or a Slack bot, your timing is going to be off. You’ve lost the "feedback loop" that tells you what’s hitting and what’s missing.

Is It Your Brain or Just the World?

We have to talk about the "context collapse" of the 2020s. We live in a hyper-sensitive, highly polarized era. Many people feel like they’re "not funny anymore" because the stakes of a failed joke have never been higher. The subconscious fear of being misunderstood or offending someone creates a "lag" in your speech. That split-second hesitation is where the funny goes to die. Comedy relies on the "Benign Violation Theory," proposed by Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren. For something to be funny, it has to be a "violation" (something wrong, or unsettling) that is also "benign" (safe). If you no longer feel safe—culturally or socially—you stop taking the risks necessary to find the "violation."

📖 Related: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

The "Funny" Fossil Record

Think back to the last time you felt truly hilarious. What was the environment? Who was there? Usually, it’s a specific "tribe" where you felt 100% psychological safety. If you’ve moved cities, changed jobs, or drifted from old friends, you might just be missing your resonance chamber.

Humor is often situational. You aren't a stand-up comedian with a tight five minutes of material; you’re a person who reacts to the world. If your world has become stagnant—same commute, same breakfast, same three news sites—your brain has no new data to work with. You're trying to bake a cake with no flour.

Breaking the Silence

The good news is that wit is a renewable resource. You don’t "lose" it permanently; it just goes into hibernation. To get back to yourself, you have to stop trying so hard. Effort is the most visible thing in a room, and nothing kills a laugh faster than the "sweat" of someone trying to be liked.

👉 See also: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

- Consume high-quality "fuel." If you’re only reading doom-scrolling headlines, your internal monologue will be grim. Listen to podcasts where people have high-level, fast-paced banter. SmartLess or even old episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm can help "re-wire" your brain to recognize comedic beats.

- Lower the bar. Don't try to be "the funny one." Aim to be the person who notices the funny thing. Observation is the precursor to wit.

- Address the "Brain Fog." If your humor loss is accompanied by fatigue or memory issues, check your health. Low Vitamin D, B12 deficiencies, or thyroid issues can flatten your affect. You can't be sharp if your biology is dull.

- Embrace the Silence. Sometimes, the reason you feel you aren't funny is that you’re forcing talk to fill the gaps. Let the silence sit. Often, the funniest thing to say is the thing that occurs to you after the pressure to speak has subsided.

The Path Back to Wit

Reclaiming your sense of humor is less about learning jokes and more about unlearning the fear of being boring. You have to give yourself permission to bomb. Every great comedian has "died" on stage thousands of times. If you make a joke and nobody laughs, the world doesn't end.

Start by finding the absurdity in your own frustration. The fact that you’re worried about being "not funny anymore" is, in itself, kind of a dark comedy. You’re a sentient ape on a floating rock, stressed out because you couldn't make another ape make a specific barking sound with their throat. When you see the meta-humor in your own predicament, the pressure starts to lift.

Actionable Steps to Recovery:

- Change your input: Stop watching the news for 48 hours. Read a humorist like David Sedaris or watch a specialized "dry" comedy.

- The "One-Liner" Rule: Try to make one person laugh a day—just one. Not a group. Just the barista or a coworker.

- Physical Play: Get out of your head and into your body. Go for a run, join a kickball league, or do something where you are likely to fail physically. It lowers your ego, and a lower ego is a prerequisite for humor.

- Journal the "Weird": Write down three things that happened today that were slightly "off" or nonsensical. Don't try to make them jokes. Just document the friction of life.

Your wit is still there. It's just buried under the laundry, the bills, and the weight of being a "responsible adult" in a complicated world. Dig it out slowly. There’s no rush. The world will still be ridiculous when you’re ready to laugh at it again.