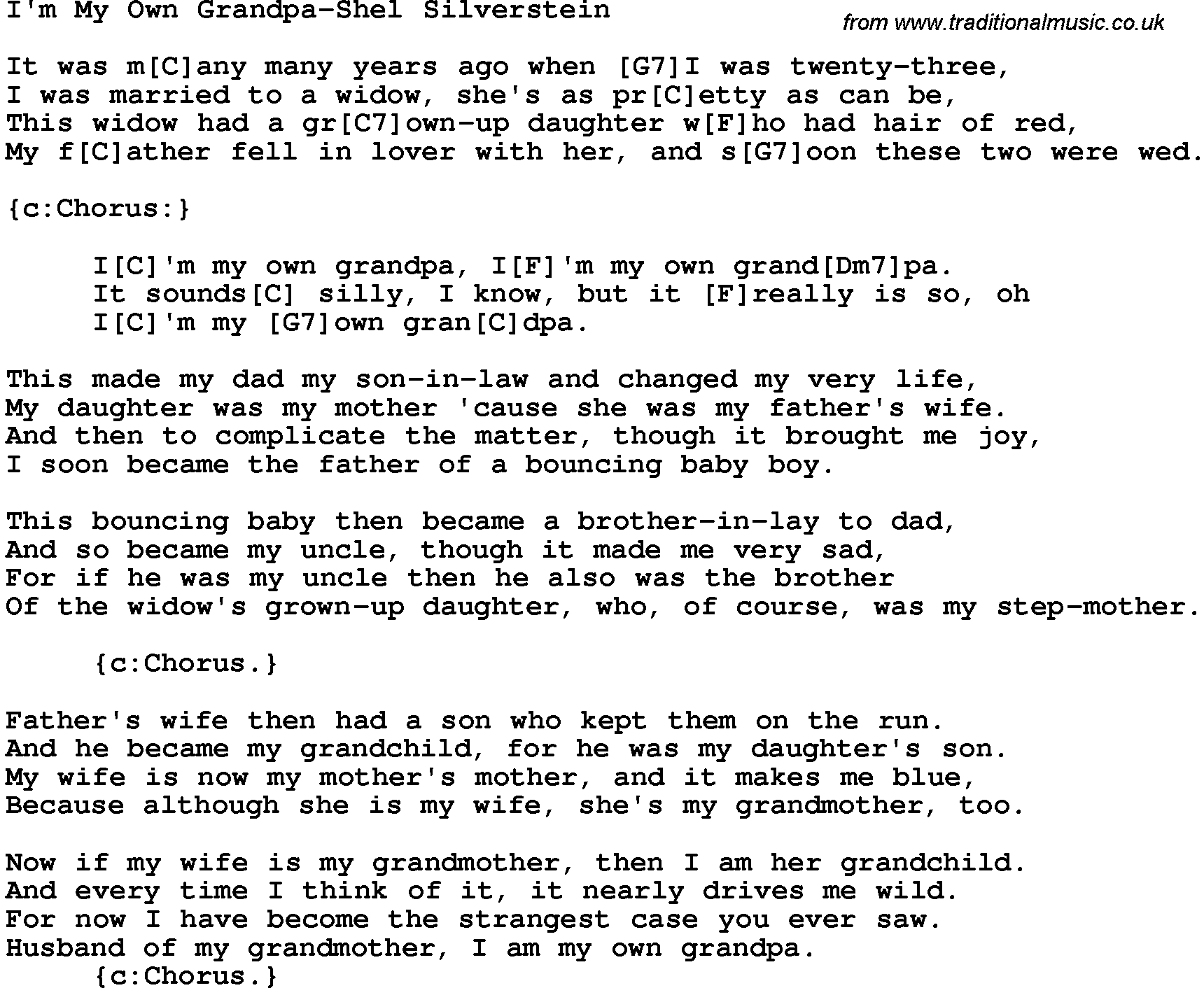

It sounds like a total fever dream. Or maybe a really messy episode of a daytime talk show. But "I'm My Own Grandpa" isn't just a catchy novelty song from the 1940s; it’s a legitimate logic puzzle that has broken the brains of listeners for nearly eighty years. You've probably heard the chorus. It’s jaunty. It’s fast. It’s deeply confusing.

The song describes a specific set of marriages that, while perfectly legal and non-incestuous, create a genealogical loop. It sounds impossible. It isn't. People often assume the lyrics are just nonsense meant to get a laugh, but the math actually checks out.

Honestly, the brilliance of the track lies in how it uses simple family definitions to create an absolute disaster of a family tree. It’s a masterpiece of lyrical engineering.

The Story Behind the Song

Dwight Latham and Moe Jaffe wrote the track in 1947. Latham was part of a group called the Jesters, and he'd actually encountered the basic idea in an old joke book or a brief anecdote attributed to Mark Twain. Twain allegedly wrote a similar piece of prose about a man who marries a widow, but Latham and Jaffe were the ones who turned it into a chart-topping hit for Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians. Later, Ray Stevens made it a staple of country-comedy.

The 1940s was a big era for novelty music, but this one stuck. Why? Because it’s a challenge. It dares you to follow along. Most people give up halfway through the second verse because their mental map of the family tree starts smoking.

Breaking Down the Genealogy (Yes, It Works)

To understand how someone becomes their own grandpa, you have to follow the marriages step-by-step. It starts simply. A guy—let's call him the Narrator—marries a widow who has a grown daughter.

Nothing weird yet.

Then, the Narrator's father (a widower) falls in love with the widow's grown daughter and marries her. This is where the gears start turning. Because the Narrator's father married the Narrator's stepdaughter, the stepdaughter is now the Narrator's stepmother.

Follow that?

If your stepmother is your stepmother, her father—in this case, the Narrator—becomes a grandfather-in-law to his own father. But it gets much tighter. When the Narrator and the widow have a baby, that baby is the half-brother of the Narrator's stepmother (the daughter of the widow). Since the stepmother is the "mother" of the Narrator's father, the baby is technically the uncle of the Narrator's father.

If the baby is the uncle of the father, the baby is also the brother of the Narrator's "grandmother" (the stepmother).

📖 Related: Why Hallmark Three Wiser Men and a Boy Is Actually a Christmas Miracle

It’s a mess.

The kicker happens when the Narrator's father and his new wife (the stepdaughter) have a son. That son is the Narrator's brother because they share the same father. However, he is also the Narrator's grandson because he is the son of the Narrator's stepdaughter.

If you are the brother of your own grandson, and your wife is the mother of your mother, you are, by the laws of kinship terminology, your own grandfather.

The Mark Twain Connection

There’s a long-standing rumor that Mark Twain actually invented this scenario. While it’s hard to pin down a specific date, a similar logic puzzle appeared in a 19th-century publication often linked to him. It was titled "A Literary Antiquity."

Twain loved these kinds of logical paradoxes. He enjoyed poking fun at the rigid structures of society. Whether he actually sat down and mapped it out or just refined an existing folk tale is debated by historians, but the DNA of the joke is definitely "Twain-esque."

It’s the kind of intellectual play that survives because it feels like a glitch in reality. We have these strict labels—father, son, grandfather—and we assume they are linear. "I'm My Own Grandpa" proves that they are actually relative.

Why Google Discover Loves This Topic

People search for this because it feels like a conspiracy theory that is actually true. It’s a "brain tickler." In an era of genealogical DNA tests like 23andMe and Ancestry.com, people are more interested than ever in the weird corners of family trees.

🔗 Read more: Why the Waterfire Saga book series is the Most Underestimated YA Fantasy Under the Sea

The song has been referenced in everything from The Muppet Show to Futurama. In Futurama, the character Philip J. Fry literally becomes his own grandfather through time travel, which is a sci-fi take on the lyrical paradox. But the song remains the "purest" version because it doesn't require a time machine—just a very specific and slightly awkward set of weddings.

Is It Legally Possible Today?

Basically, yes.

While laws regarding marriage vary wildly by jurisdiction, most Western laws focus on prohibiting marriages between blood relatives (consanguinity). In the song's scenario, no blood relatives ever marry. The Narrator marries a widow (no relation). The Father marries the widow's daughter (no relation).

The biological lines remain clean. It’s the legal lines that get tangled.

In a modern court, this wouldn't raise many eyebrows other than some confused looks from the clerk filing the paperwork. There is no incest. There is just a very compressed social circle.

The Cultural Legacy of a Paradox

It’s rare for a song from 1947 to remain culturally relevant without being a "classic" in the vein of Sinatra or Elvis. This track survives because it’s a puzzle. It’s an "earworm" that demands you pay attention.

📖 Related: Why Hustle & Flow Still Matters: The Gritty Truth Behind the Memphis Masterpiece

If you listen to the Ray Stevens version, he performs it with a frantic energy that mirrors the listener's growing confusion. By the time he reaches the end, he’s shouting the logic because it’s the only way to keep the structure from collapsing.

It has become a shorthand for any overly complicated situation. If a political alliance or a corporate merger gets too "incestuous" or cyclical, someone will invariably make a joke about being their own grandpa.

Practical Takeaways for Logic Enthusiasts

If you want to explain this to someone without sounding like a crazy person, use a piece of paper. Don't try to do it verbally.

- Draw the two initial couples. Label the Narrator and the Widow. Label the Father and the Daughter.

- Connect the marriages. Use solid lines for the marriages and dotted lines for the parent-child relationships.

- Trace the titles. Instead of looking at names, look at the titles. Ask, "What is this person's relationship to the Narrator?"

- Identify the "Uncle-Son." The moment you see that the Narrator's son is also the brother of his stepmother, the "grandfather" realization clicks.

It’s a great exercise in understanding how systems of logic can be technically correct but intuitively "wrong." The song isn't just a joke; it’s a lesson in semantics. We define family through roles, and when those roles overlap, the definitions break.

If you ever find yourself in a deep dive on YouTube or Spotify, look up the Jesters' original 1947 recording. It’s slower and more deliberate than the modern covers, making it much easier to track the "evidence" of how the Narrator ended up in such a bizarre predicament.

The next time someone tells you something is "logically impossible," remember the man who married the widow and whose father married the daughter. It’s a reminder that life, and law, can be much weirder than fiction.