Walking down the Jirón Ica in the heart of Lima’s historic center, you’ll probably walk right past a dozen different colonial buildings without blinking. They’re everywhere. But then you hit the facade of the Iglesia y Convento de San Agustín, and honestly, it’s a total trip. It’s like the stone itself has been whipped into a frenzy of curls and figures. You’ve got this massive, ornate Churrigueresque portal that looks less like a building and more like something carved out of ivory or bone.

It's one of those places that feels heavy with history. It’s not just the smell of old incense or the cool air that hits you when you step inside. It’s the weight of the 1500s. The Augustinians didn't just show up to build a chapel; they were basically setting up a spiritual and intellectual powerhouse in the "City of Kings."

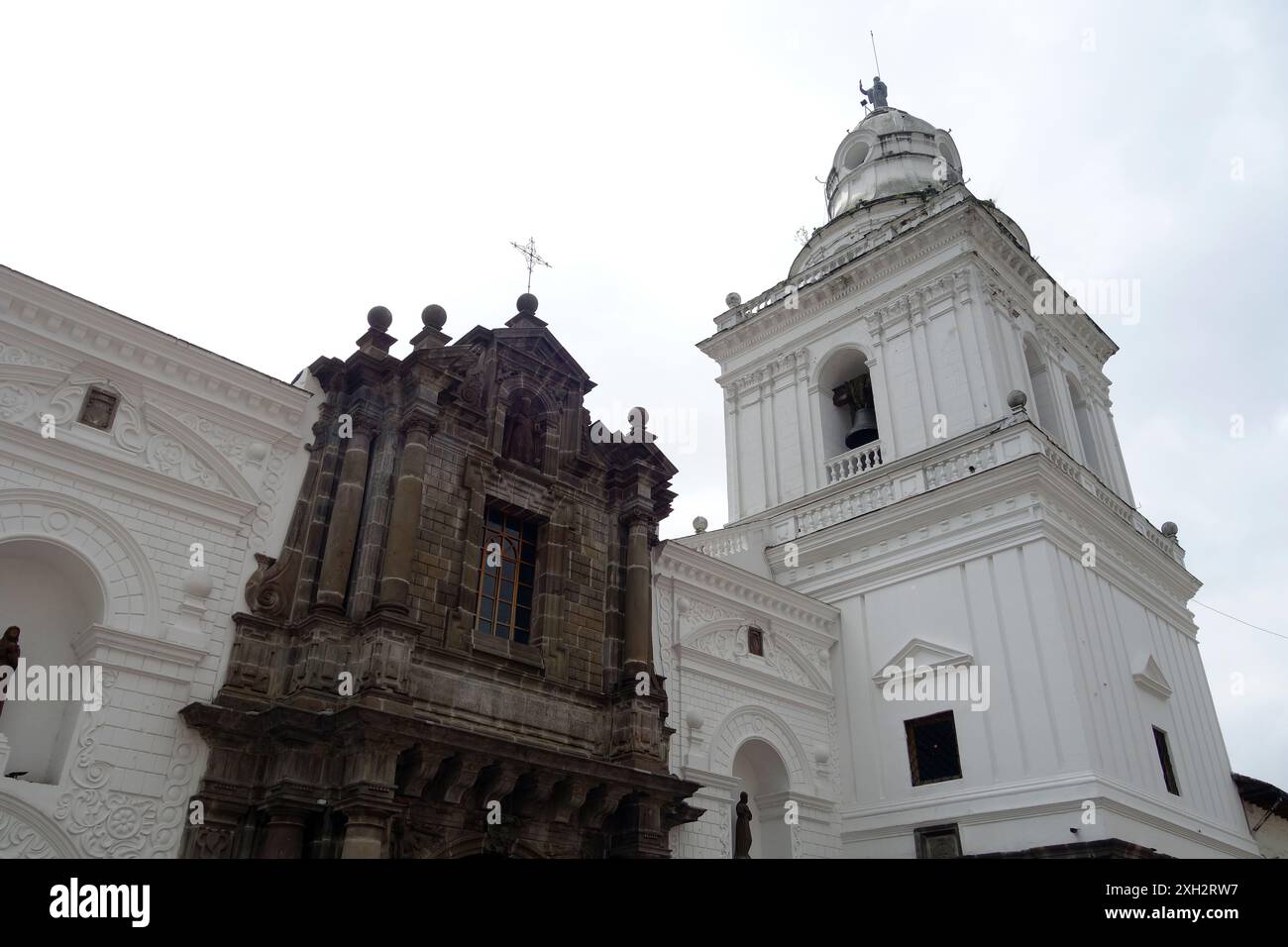

The Facade That Survived Everything

Let’s talk about that front door. Most of what you see today is a miracle of survival. Lima is basically a punching bag for tectonic plates, and the Iglesia y Convento de San Agustín has been knocked down more times than a clumsy boxer. The 1746 earthquake—the big one that leveled almost everything—did a real number on this place.

What’s wild is that the facade, completed around 1710, actually stood its ground. It’s the only part of the original structure that’s still mostly authentic to that era. It’s carved from dark stone, a style known as estípite baroque, where the columns look like inverted pyramids or stacked jewels. Look closely and you’ll see Saint Augustine himself standing there, surrounded by other saints and intricate floral patterns that feel almost claustrophobic in their detail. It's meant to overwhelm you. That was the whole point of the Counter-Reformation: make the architecture so stunning that you couldn't help but feel the "glory of God."

📖 Related: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

A Rough History of Rebuilding

If you think the church looks a bit mismatched, you're not wrong. It's a patchwork quilt of centuries. After the 1746 quake, they patched it up. Then came the Pacific War in the 1880s. Chilean troops used the convent as a barracks, which, as you can imagine, wasn't great for the woodwork. But the real kicker was the civil conflict in 1895.

The church was caught in the crossfire between the forces of Andrés Avelino Cáceres and Nicolás de Piérola. It was bombarded. Parts of it were basically rubble. Because of that, a lot of the interior you see now is actually a "neo-colonial" reconstruction from the early 20th century. It’s a bit of a bummer that the original gold-leaf altars are mostly gone, replaced by more sober marble and wood, but the sheer scale of the space still hits hard.

The convent side of things is where the real "Old Lima" vibes are. The cloisters are quiet. It’s a massive contrast to the chaotic honking of taxis right outside the walls. You can still see some of the original Sevillian tiles (azulejos) that have survived the dampness and the tremors. These tiles were the ultimate flex in the 17th century; importing them from Spain meant you had serious cash.

👉 See also: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

The Death of Saint Augustine

If you only see one thing inside, make it the "Muerte de San Agustín." It’s a sculpture by Baltazar Gavilán, who was kind of a rockstar of the limeño baroque scene. There’s a legend—probably a bit exaggerated, but still cool—that Gavilán was so spooked by his own realistic carvings of death that he suffered a heart attack.

The sculpture shows the saint at the moment of his passing. The realism is haunting. It isn’t that shiny, plastic-looking religious art you see in modern gift shops. It’s visceral. It captures that specific Spanish colonial obsession with the thin line between life and the afterlife.

What Most People Miss

People usually just snap a photo of the facade and keep walking toward the Plaza de Armas. That’s a mistake. You’ve gotta look at the ceiling in the sacristy. It’s one of the few places where the Mudéjar (Moorish-influenced) woodwork survived. The geometry is mind-bending. It’s a reminder that the people who built Lima weren’t just Spaniards; they brought a mix of Mediterranean influences that had been stewing for 800 years.

✨ Don't miss: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

The Iglesia y Convento de San Agustín also played a huge role in education. This wasn't just a place for Sunday mass. It was a university hub. The San Ildefonso College was attached to it, and for a long time, it was the intellectual rival to the Jesuits and the Dominicans. If you wanted to be anyone in colonial Lima, you were probably arguing theology or law somewhere within these walls.

Practical Tips for Visiting

The church is located at the corner of Jirón Ica and Jirón Camaná. It's super central. Here's the deal:

- Timing: They usually open early for morning mass and then again in the late afternoon. If you go midday, the doors might be shut tight. Aim for 9:00 AM or 5:00 PM.

- The Convent: Access to the cloisters is separate and can be a bit hit-or-miss depending on whether the monks are feeling social or if there’s a private event. It’s worth asking at the small side door.

- Photography: Be cool about it. It’s still an active place of worship. Don't be that person using a flash during a funeral or a wedding.

- Nearby: You’re literally two blocks from the Teatro Municipal. It’s a great area to just wander and see how the old aristocracy used to live before they all moved out to Miraflores and San Isidro.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

Don't just look at the building as a whole; treat it like a scavenger hunt.

- Find the "hidden" details on the facade: Look for the small birds and grapes tucked into the stone carvings—this is the Mestizo Baroque influence where local indigenous carvers snuck their own symbols into the European designs.

- Check the floor: In some areas, you can see the markers for old crypts. Lima used to bury its wealthy under the floorboards before the Presbítero Maestro cemetery was built outside the city walls.

- Compare the styles: Stand in the center of the nave and look at the difference between the ornate, surviving colonial elements and the cleaner, more modern repairs. It tells the story of a city that refuses to stay broken.

The Iglesia y Convento de San Agustín isn't a museum frozen in time. It’s a survivor. It’s been burned, shaken, shot at, and neglected, yet that stone facade still stares down the street like it owns the place. Which, honestly, it kinda does.

To get the most out of your visit, start by examining the exterior carvings for at least ten minutes before heading inside; the narrative of the stone tells a much deeper story than the interior ever could. Once inside, head straight to the sacristy to find the Mudéjar ceiling—it's the most authentic piece of the 17th century left in the building.