You’ve seen them in every school nurse’s office or tucked away in the back of a dusty medical pamphlet. Those grids. Those boxes. The ideal height weight chart has been the gatekeeper of "healthy" for decades, telling us exactly where we should land if we want to be considered normal. But honestly? Most of those charts are relics. They’re based on data that is sometimes a century old, often ignoring how actual human bodies are built in the real world. If you’ve ever felt like a failure because a chart said you were "overweight" while you were literally training for a marathon, you aren't alone.

Health is messy.

It’s not just a point where X meets Y on a graph. We’re going to talk about why these charts exist, where they fail, and what the medical community is actually using in 2026 to figure out if you're in a good spot or if you need to make some changes.

Where the Ideal Height Weight Chart Actually Came From

Believe it or not, the "ideal" wasn't originally a medical standard. It was a financial one. Back in the early 20th century, insurance companies—specifically Metropolitan Life Insurance Company—wanted to predict when people were going to die. They needed to know how much to charge for premiums. They looked at their policyholders (who were mostly white, middle-class men at the time) and noticed that people within a certain weight range for their height tended to live longer.

Boom. The "MetLife tables" were born.

The problem is that a 1940s insurance actuary isn't a modern doctor. These early charts didn't account for muscle mass, bone density, or ethnicity. They just saw a number on a scale. Even the modern BMI (Body Mass Index) scale, which many people confuse with a standard ideal height weight chart, was created by Adolphe Quetelet, a mathematician, not a physician. He explicitly stated it shouldn't be used to judge the health of an individual, yet here we are, 200 years later, still obsessing over it.

The Problem with "Average"

If you look at a standard chart for a 5'9" male, it might tell you the "ideal" range is between 144 and 176 pounds. Sounds simple. But what if that guy is a rugby player with a 32-inch waist and massive quads? He’s going to clock in at 210 pounds easily. The chart flags him as obese. On the flip side, someone else could be 160 pounds but carry all their weight in their midsection—what doctors call "visceral fat"—which is way more dangerous for heart health than the athlete's muscle. The chart says the second guy is perfect.

It's wrong.

Breaking Down the Numbers for Men and Women

Biologically, men and women carry weight differently, and most modern medical practitioners have moved away from a single, static ideal height weight chart toward something a bit more nuanced.

For women, essential body fat is higher. You need it for hormonal balance and reproductive health. If a woman's weight drops too low according to a generic chart, her period might stop, her bone density could plummet, and she might develop osteoporosis. For men, the "ideal" weight often ignores the fact that they tend to have higher bone density and more skeletal muscle.

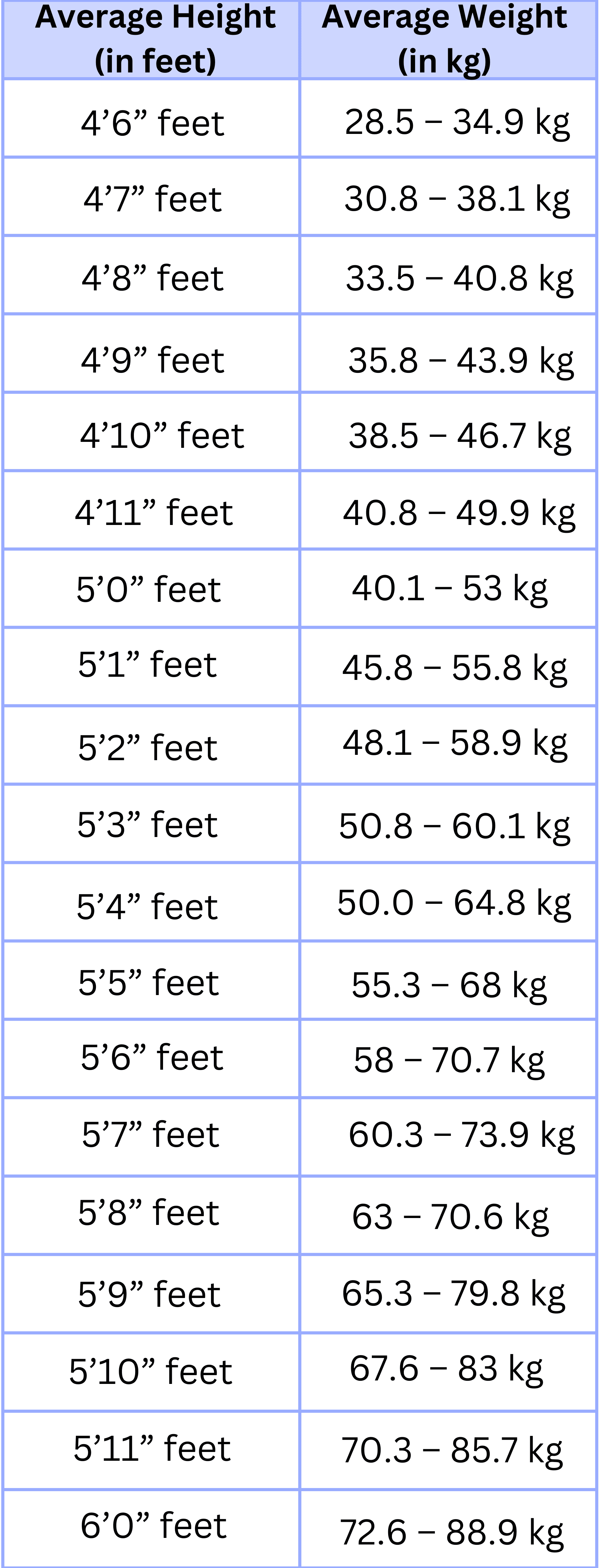

Let's look at some rough estimates often used in clinical settings today, but keep in mind, these are strictly guidelines, not laws of physics:

For a woman who is 5'4" (163 cm), the traditional range is often cited as 110 to 140 pounds. But if she’s hitting the gym and has a high lean mass index, 150 might be her healthiest state.

For a man who is 5'10" (178 cm), the "standard" suggests 149 to 183 pounds. Yet, a man with a "large frame" (yes, frame size is a real clinical metric involving wrist circumference) might naturally sit at 190 without a single health complication.

👉 See also: Why the Cabbage Soup Detox Recipe Still Hits the Mainstream (And How to Actually Make It)

Beyond the Scale: What Really Matters Now

If the ideal height weight chart is a blunt instrument, what’s the scalpel? In 2026, we’re looking at much more specific data points.

Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) This is arguably more important than your total weight. To find it, you measure the smallest part of your waist and the widest part of your hips. Divide the waist by the hip. For men, a ratio above 0.90 suggests you're carrying too much abdominal fat. For women, it’s 0.85. This matters because abdominal fat is metabolically active; it pumps out inflammatory markers that mess with your insulin and your heart.

Body Composition Analysis This is where the magic happens. Tools like DXA scans (Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry) or even high-end bioelectrical impedance scales can tell you how much of your weight is actually fat versus muscle or bone.

Think about it this way:

- Person A: 200 lbs, 35% body fat.

- Person B: 200 lbs, 15% body fat.

The ideal height weight chart sees them as identical. Biology sees them as two completely different species of health.

Why Your "Frame" Isn't Just an Excuse

You’ve heard people say they are "big-boned." People usually laugh it off as an excuse for being overweight, but clinical anthropometry actually supports the idea of frame sizes.

To check yours, wrap your thumb and middle finger around your opposite wrist.

💡 You might also like: What Happens If You Eat Too Much Sugar: The Messy Reality Your Body Faces

- If they overlap: Small frame.

- If they just touch: Medium frame.

- If there’s a gap: Large frame.

A large-framed person can carry 10% to 15% more weight than a small-framed person of the same height and still be "lean." A chart that doesn't ask about your wrist size is missing a huge piece of the puzzle.

The Role of Ethnicity in Weight Standards

This is a huge blind spot in the history of the ideal height weight chart. Most charts were calibrated on Caucasian populations. However, research has shown that health risks start at different weights for different groups.

For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Diabetes Association have noted that people of South Asian descent often face higher risks of Type 2 diabetes and heart disease at a lower BMI than Caucasians. For these groups, the "overweight" threshold might actually need to be shifted down. Conversely, some studies suggest that for people of African descent, higher muscle density might mean the "overweight" threshold on a standard chart is too restrictive.

One size does not fit all. It never did.

How to Actually Use This Information

So, you’ve looked at the ideal height weight chart and you’re outside the lines. What do you do? Don't panic. Use the data as a "check engine" light, not a "totaled car" sign.

- Check your blood work. Weight is a proxy for health, but blood pressure, A1C (blood sugar), and cholesterol are the actual health markers. If your weight is high but your metabolic markers are perfect, you might just be a "metabolically healthy" larger person.

- Measure your waist. If your weight is "normal" but your waist is expanding, that's a bigger red flag than being 10 pounds "over" on a chart.

- Assess your functionality. Can you walk up three flights of stairs without gasping? Can you carry your groceries? Can you sit on the floor and get back up without using your hands? These functional tests often correlate more closely with longevity than a scale ever will.

Actionable Steps for a Healthier Metric

Forget the 1950s charts. If you want to know where you stand, follow these steps to get a real picture of your health.

📖 Related: Can Bubble Baths Cause a UTI? What Your Doctor Might Not Tell You

- Ditch the daily weigh-in. Weight fluctuates by 3-5 pounds a day based on salt, water, and hormones. It’s a noisy metric. Move to a weekly average if you must.

- Prioritize Waist-to-Height Ratio. Keep your waist circumference to less than half of your height. If you are 70 inches tall, your waist should be 35 inches or less. This is much more accurate than the ideal height weight chart for predicting health outcomes.

- Get a DEXA scan. If you’re serious about your health, find a local imaging center. It costs about $100-$150, but it will tell you exactly how much visceral fat you have. That is the only "weight" that truly endangers your life.

- Focus on Strength. Instead of aiming for a lower number on the chart, aim for a higher number on your lifts or more reps in your bodyweight squats. Muscle is metabolically protective.

The chart is a map, but you are the terrain. Don't let a grid from the 1940s tell you how to feel about your body today. Focus on the markers that actually predict how long and how well you will live.