Ever wonder why your car tires look a little flat on a freezing January morning? It’s not a leak. Usually, anyway. It’s just the ideal gas law doing its thing right in your driveway. Most of us remember the formula from high school chemistry—that $PV = nRT$ string of letters—and we immediately think of dusty chalkboards and painful exams. But honestly, if you’re into anything from scuba diving to engineering high-performance engines, this equation is basically your best friend. It’s the "cheat code" for how the physical world breathes.

Physics is messy. Gases are messier. To make sense of the chaos, scientists like Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron back in 1834 decided to simplify things. He took the work of legends like Robert Boyle and Amedeo Avogadro and smashed them together. The result was a way to predict how a gas behaves if we pretend the molecules are perfect little billiard balls that don't stick to each other.

Is it "real"? Not exactly. But it's close enough that we use it to launch rockets.

Why the Ideal Gas Law is Actually a Lie (And Why That’s Okay)

Here is the thing: "Ideal" gases don't actually exist. In the real world, gas molecules have a tiny bit of volume and they definitely have feelings for each other—meaning they experience intermolecular forces. If you get a gas cold enough or squeeze it hard enough, the ideal gas law starts to fall apart. This is why we have the Van der Waals equation for the "real" stuff.

But for most of the stuff you'll encounter in daily life—air in a room, steam in a pipe, or the helium in a balloon—the error is so small it doesn't even matter.

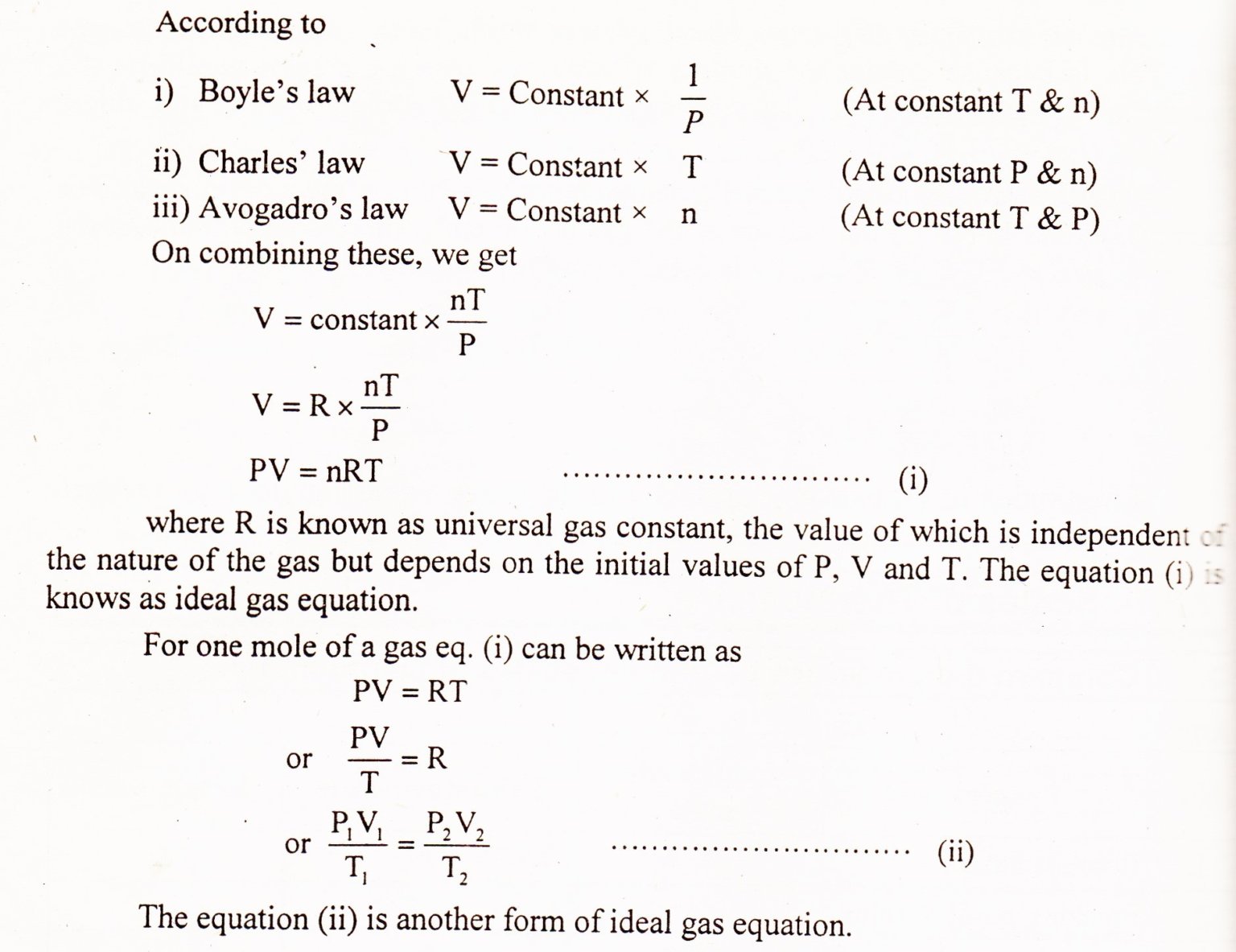

The $PV = nRT$ Breakdown

Let's get the math out of the way so we can talk about the cool stuff.

- P is Pressure: Think of this as how hard the gas is hitting the walls of its container.

- V is Volume: How much space it takes up.

- n is the number of moles: Basically, how much "stuff" is in there.

- R is the Universal Gas Constant: It's the "glue" that makes the units work together. Usually $0.0821$ if you're using liters and atmospheres.

- T is Temperature: This is the big one. It must be in Kelvin. If you use Celsius, the whole thing breaks.

Imagine a piston. You push down on it, which decreases the Volume. What happens? The Pressure goes up. Why? Because you’ve jammed all those molecules into a smaller space and they’re hitting the walls more often. It’s simple, intuitive, and remarkably consistent.

The Scuba Diver’s Nightmare

If you’ve ever gone diving, you know about the "bends." It’s terrifying. This is a direct application of gas laws. When you’re deep underwater, the pressure is immense. According to our law, if you increase the pressure on a gas, you're forcing more of it into a smaller space—or in this case, forcing more nitrogen to dissolve into your blood.

If you come up too fast?

The pressure drops instantly. The volume of that nitrogen gas wants to expand rapidly. It’s exactly like shaking a soda bottle and then ripping the cap off. The bubbles form in your joints and bloodstream. It hurts. A lot. This is why dive computers are basically just ideal gas law calculators strapped to your wrist. They’re tracking the math so your blood doesn't turn into a carbonated beverage.

🔗 Read more: Mac Tools Impact Gun Options: What Most Mechanics Get Wrong

Weather and the "Empty" Soda Bottle Trick

You can see the ideal gas law in action with a simple kitchen experiment. Take an empty plastic soda bottle, put the cap on tight, and throw it in the freezer. Come back an hour later. The bottle looks like it’s been crushed by an invisible hand.

Did air leak out? Nope.

The temperature ($T$) dropped. Since the bottle is sealed, the amount of gas ($n$) stayed the same. To keep the equation balanced, the pressure or the volume has to drop. Since the plastic is flexible, the volume shrinks. This is also why airplanes have pressurized cabins. At 30,000 feet, the atmospheric pressure is so low that your lungs wouldn't be able to grab enough oxygen molecules to keep you conscious. The plane’s systems use the relationship between temperature and pressure to keep you breathing comfortably while it’s -50 degrees outside.

Engineering the Future

In the automotive world, the ideal gas law governs the combustion engine. When the fuel-air mixture is compressed in the cylinder, the pressure and temperature spike. If it gets too hot too fast, the fuel ignites before it's supposed to. That's "knock." Engineers spend thousands of hours balancing $P$ and $T$ to get the most power without blowing the engine to bits.

Even in the world of green tech, like hydrogen storage, we're fighting these laws. Hydrogen is great, but it takes up a massive amount of volume at room temperature. To fit enough in a car to drive 300 miles, we have to crank the pressure up to 10,000 psi. That requires tanks made of carbon fiber because, as the law tells us, that much pressure is literally trying to explode the container every second of every day.

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

You don't need a PhD to use the ideal gas law to make your life easier.

- Check your tires when it's cold. For every 10-degree drop in temperature, you're looking at a 1-2 psi drop in pressure. Don't buy new tires; just add air.

- Baking at high altitudes. If you're in Denver, the lower atmospheric pressure means your bread will rise faster but might collapse because the structure hasn't set yet. You have to tweak the "V" and "T" variables in your oven and recipe.

- Storage Safety. Never leave a spray paint can (fixed volume, high pressure) in a hot car. As $T$ goes up, $P$ goes up. Eventually, the metal can't hold it.

The ideal gas law is a reminder that the universe follows rules. They might be "idealized" versions of the truth, but they give us a map to navigate everything from the bubbles in our soda to the atmosphere of Mars.

Next time you see a hot air balloon, don't just look at the colors. Think about the burner. It’s increasing $T$, which increases $V$, making the air inside less dense than the air outside. You're literally watching math lift people into the sky.

To get a better handle on this, try calculating the molar mass of a common gas using a DIY setup with a butane lighter and a graduated cylinder. It's the most common college lab for a reason: it makes the invisible, visible. Stop treating $PV=nRT$ as an abstract concept and start seeing it as the manual for the air around you.