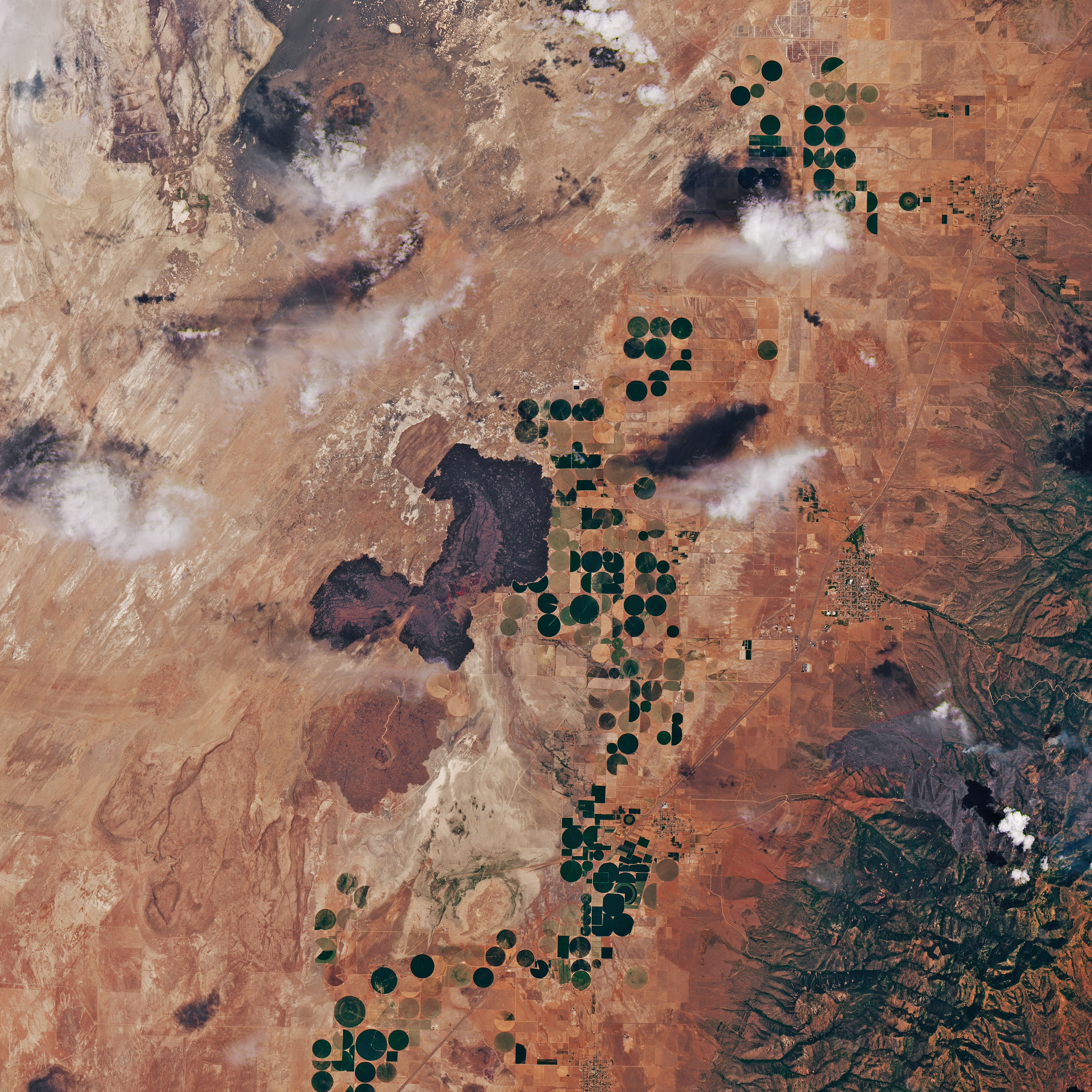

You’re driving through the high desert of Millard County, Utah, and suddenly the sagebrush gives way to a jagged, obsidian-black wasteland that looks like it belongs on the moon. This is the Ice Springs lava flow. It’s raw, it’s sharp enough to shred a pair of hiking boots in twenty minutes, and honestly, it’s one of the most misunderstood geological features in the American West.

Most people assume Utah is a place of ancient, dead geology—red rocks carved over millions of years. But Ice Springs is different. It’s young. In geological terms, it’s basically an infant.

For a long time, the "official" word was that this lava cooled only about 660 to 700 years ago. That would mean ancestors of the Modern Paiute and Fremont people might have watched the sky turn black as fire fountains shot hundreds of feet into the air. Newer research from the Utah Geological Survey has pushed that date back a bit—closer to 10,000 years—but in the grand scheme of the Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history, that’s still a blink of an eye.

Why is it called "Ice Springs" anyway?

It sounds like a total contradiction. How can a literal volcano be named after ice?

The name comes from a bizarre natural phenomenon found within the cracks of the basaltic aa lava. Because the rock is so porous and acts as a world-class insulator, winter snow and cold air get trapped deep inside the volcanic vents and "crevices." Even in the middle of a blistering 100°F Utah summer, you can sometimes find ice lingering in the deep shadows of the caves.

Early settlers and Indigenous groups knew this. They used the lava field as a natural refrigerator. Imagine trekking across a desert where the ground is literally radiating heat, only to reach into a crack in the rock and find a block of ice. It’s kinda mind-blowing.

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The Cinders: A Cluster of Violence

The Ice Springs flow didn't just come from one hole in the ground. It erupted from a complex of four main cinder cones:

- Crescent Crater

- Miter Crater

- Terrace Crater

- Pocket Crater

These aren't your typical postcard volcanoes. They are "cinder and spatter" cones. During the eruption, the magma was so gas-rich that it didn't just ooze; it fountained. Think of it like opening a shaken soda bottle. The "spatter" consists of globs of molten rock that flew through the air and landed with a wet thud, sticking together to form the steep, rugged walls of the craters we see today.

The Quartz Mystery

If you look closely at the rocks at Ice Springs—and I mean really closely—you’ll see something that shouldn’t be there. Small, clear crystals of quartz and chunks of granite are embedded right in the black basalt.

Geologists call these xenoliths.

Basically, as the basaltic magma was screaming toward the surface from deep in the mantle, it ripped off pieces of the Earth’s crust along the way. These "stranger rocks" didn't have time to melt completely before the lava cooled. It’s a literal snapshot of the layers of earth hidden miles beneath your feet.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

Visiting the Black Rock Desert

Getting to the Ice Springs lava flow isn't like visiting a National Park. There are no paved boardwalks or gift shops. You’re headed into the Black Rock Desert, about 9 miles west of Fillmore, Utah.

The terrain here is brutal. The primary type of rock is aa lava (pronounced "ah-ah"). Legend has it the name comes from the sound people make when they walk on it barefoot. It’s jagged, loose, and incredibly abrasive. If you trip, you aren't just getting a bruise; you’re getting sandpapered.

Survival Tips for the Flow

- Footwear is everything. Forget your sneakers. You need stiff-soled hiking boots with good ankle support. The "clinkers" (the loose rocks on the surface) shift under your weight like a pile of broken glass.

- Water is a lie. There are no springs you can actually drink from. The "Ice Springs" are deep, dangerous, and often inaccessible. Bring twice as much water as you think you’ll need.

- Watch the heat. The black rock absorbs sunlight. In July, the ground temperature can easily exceed 130°F. Your dog's paws will burn in seconds—honestly, it’s best to leave pets at home for this one.

Is it going to erupt again?

This is the question everyone asks. The Black Rock Desert volcanic field has been active for about 2.7 million years. It’s not "dead" in the way people think. It’s "dormant."

The Ice Springs event was just the most recent pulse in a very long heartbeat. Geologists generally agree that the region is still tectonically active. While there’s no sign of an imminent eruption today, the "next" volcanic event in Utah is statistically most likely to happen right here or in the nearby Markagunt Plateau.

But don't panic. You'll get plenty of warning. Volcanic eruptions in the Great Basin are usually preceded by a swarm of small earthquakes as magma breaks through the crust. We haven't seen that lately.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

What you can actually do there

Most people go to Ice Springs for the photography or the solitude. Standing in the center of Crescent Crater, the silence is heavy. You can see the distinct "flow lobes" where the lava pushed through the breached walls of the cones and spilled out across the desert floor.

There’s also a bit of a "treasure hunt" aspect to the area. Because the lava is so young, the flow features—like pressure ridges and lava tubes—are perfectly preserved. You can see "ropy" pahoehoe textures in some spots, though the jagged aa dominates the landscape.

Actionable Steps for Your Trip

If you’re planning to check out the Ice Springs lava flow, don't just wing it. The desert is unforgiving.

- Check the Weather: If it’s over 90°F in Fillmore, it’s too hot to be on the lava. Aim for a spring or fall morning.

- High Clearance is Key: The roads out to the Cinders are gravel and dirt. A standard sedan can make it if the roads are dry, but a high-clearance vehicle is much safer, especially if there's been recent rain which turns the desert silt into "greasewood" mud.

- Use GPS: The landscape is monochromatic. It is incredibly easy to lose your bearings once you start hiking into the craters. Download offline maps of the Millard County area.

- Respect the Mining: Parts of the area are actively mined for red cinders (used in landscaping and road salt). Stay away from the heavy machinery and respect the "No Trespassing" signs on private claims.

- Leave No Trace: This is a fragile ecosystem despite its tough appearance. Pack out every scrap of trash. The desert doesn't break down waste quickly.

The Ice Springs lava flow is a reminder that the Earth is alive and moving right under our feet. It’s a place of extremes—ice in the summer, fire in the past, and a silent, black future that’s waiting for the next pulse of magma to wake it up. If you want to see what the world looked like when it was being born, this is where you go.

Next Steps for Your Visit:

- Coordinate with the BLM: Contact the Bureau of Land Management (Fillmore Field Office) to check current road conditions before heading out.

- Gear Up: Ensure you have a full-size spare tire and a basic first-aid kit that includes plenty of bandages—lava rock cuts are notoriously messy.

- Map Your Route: Locate the turnoff from Highway 15 onto the gravel roads leading west toward the "Cinders" to avoid getting lost in the maze of ranching trails.