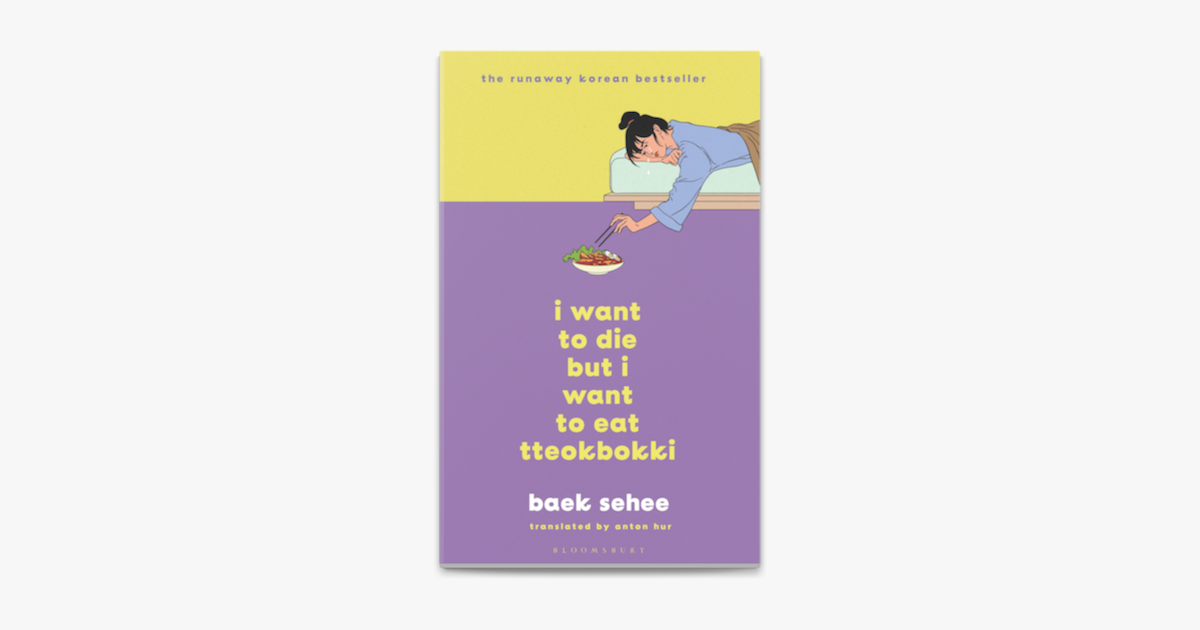

Ever felt totally fine on the outside but completely hollow behind your ribs? Baek Sehee did. She wrote it all down. Then it became a global phenomenon. Honestly, the title I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is probably one of the most honest things ever printed on a book jacket. It captures that weird, annoying paradox of being human. You can feel like the world should just end, yet you still crave a spicy snack. It’s dark. It’s funny. It’s painfully real.

Baek Sehee wasn't a doctor or a famous monk. She was a social media professional working at a publishing house. She had "dysthymia," which is basically a persistent, low-grade depression that doesn't always stop you from functioning but makes everything feel gray. Her book isn't a polished self-help guide. It’s mostly just transcripts. You’re reading her actual therapy sessions. It’s voyeuristic, sure, but it’s also a mirror for anyone who’s ever felt like a "fine" person who is secretly struggling to stay afloat.

What is Dysthymia anyway?

Most people think depression means you can’t get out of bed. Sometimes it does. But I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki focuses on the middle ground. Dysthymia—now often called Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD)—is like a constant background noise of sadness. It’s the low hum of a refrigerator you can't unplug. Baek describes it through her conversations with her psychiatrist. She talks about her obsession with how others see her. She talks about her deep-seated insecurities.

The book resonated so hard in South Korea—and later the world—because it challenged the "hustle culture" that demands perfection. You see her struggle with the most basic interactions. Should she say this? Did she look weird when she laughed? It’s exhausting. The clinical term might be PDD, but for Baek, it’s just life. The sessions cover a twelve-week period. We see her go through peaks and valleys. One day she’s okay; the next, she’s spiraling because of a minor comment from a coworker.

The Tteokbokki Paradox

Why the food? Why tteokbokki? If you aren't familiar, tteokbokki is a beloved Korean street food—chewy rice cakes in a spicy, slightly sweet red sauce. It’s comfort in a bowl. The title highlights the absurdity of the human brain. You can be standing on the edge of a metaphorical cliff, thinking about the end, and then your stomach growls. It reminds you that you’re still an animal with needs. It’s the "light" that keeps her tethered.

This isn't a book that promises a cure. Don't go into it expecting a "five steps to happiness" list. You won't find one. Instead, you find a woman who learns to live with the "gray." She learns that wanting to eat tteokbokki is a victory. It’s a tiny, spicy reason to keep going for another hour.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Breaking the Stigma in South Korea

South Korea has a complex relationship with mental health. For a long time, it was a "don't ask, don't tell" situation. High pressure, high competition. Baek Sehee self-published this book through a crowdfunding campaign because she wasn't sure if a traditional publisher would take a risk on something so raw. It blew up. It didn't just sell; it started a national conversation.

The book's success opened the floodgates for "essay" literature in Korea—books that are part memoir, part therapy, and entirely unpolished. It gave people permission to be messy. Even BTS's RM was spotted with the book, which, as you can imagine, sent its popularity into the stratosphere. But even without the K-pop boost, the content stands on its own. It’s brave. Writing down your deepest, most embarrassing thoughts for the world to read is a special kind of courage.

Why the Dialogue Format Works

The book is structured as a series of back-and-forths.

- Baek: Explains a feeling.

- Psychiatrist: Asks a probing question.

- Baek: Digs deeper.

This format is genius because it removes the "preachy" tone of most mental health books. You aren't being told how to feel. You are watching someone else figure out how they feel. You become the fly on the wall. Sometimes, the psychiatrist’s advice is a bit clinical, and you might even disagree with it. That’s the point. It’s a real relationship between two humans trying to navigate a foggy brain.

Understanding the "Shadow"

One of the most profound parts of I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is how Baek addresses her "shadow" self. She deals with extreme self-loathing. She looks at her friends and wonders why they like her. She feels like an impostor. If you’ve ever felt like you’re just pretending to be a grown-up, this book will hit you like a freight train.

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

She explores "high-functioning" depression with brutal honesty. She can go to work. She can meet friends. She can buy clothes. But inside, she's constantly tallying up her perceived failures. The psychiatrist helps her realize that she is focusing only on her extremes—either she’s a total success or a total failure. There is no middle ground in her mind. Learning to live in the "middle" is her biggest challenge.

Critical Reception and Global Impact

When the English translation by Anton Hur came out, some Western readers were surprised by the tone. It’s very quiet. It doesn't have the dramatic arc of a Hollywood memoir. There’s no big "aha!" moment where everything is fixed. Some critics found it repetitive.

But that's exactly why it's authentic. Therapy is repetitive. Healing isn't a straight line; it’s a messy scribble that occasionally loops back on itself. The book's global success proves that the "tteokbokki feeling" is universal. It doesn't matter if you live in Seoul, London, or New York—feeling "fine but not okay" is a modern epidemic.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Mental Health

If you're reading this because you feel a bit like Baek Sehee, here is what you can actually do. First, stop looking for a "cure" and start looking for "management." Baek doesn't get "fixed." She gets better at identifying her triggers.

Notice the "all-or-nothing" thinking. Are you telling yourself that because you messed up one task, you’re a failure at your job? That’s the distortion. Try to find the "gray" area. You did one thing wrong, and ten things right. Both are true.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

Identify your "Tteokbokki." What is the tiny, silly thing that keeps you grounded? Maybe it’s a specific latte. Maybe it’s watching videos of capybaras. Don't judge the "smallness" of your joy. If it works, it works.

Track your moods without judgment. Baek’s book started as a diary of her sessions. Try writing down your feelings for just five minutes a day. Don't worry about being "deep." If you’re annoyed that the bus was late, write that down. Seeing your thoughts on paper makes them feel less like an internal storm and more like data.

Seek professional help if you can. The book is a great companion, but it’s not a replacement for a therapist. If you feel like you’re drowning, please reach out to a professional. There’s no shame in having a "brain mechanic" look under the hood.

The legacy of I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is simple: it’s okay to be imperfect. It’s okay to be sad and hungry at the same time. You don't have to be "fixed" to be worthy of a good meal and a decent life. Accept the gray, eat the spicy rice cakes, and keep going.