You’ve seen it in every anime. The protagonist stands under a cherry blossom tree, face flushing a deep crimson, and finally stammers out those three heavy words. But honestly? If you walked up to a partner in Tokyo and dropped a direct translation of "I love you," things might get weird. Real fast.

Japanese is a high-context language. That basically means what you don't say is often more important than what you actually spit out. In English, we throw "love" around like confetti—we love pizza, we love our moms, we love that new Netflix show, and we love our partners. In Japan, that word carries a weight that can feel almost suffocating if used at the wrong time.

👉 See also: Why Go the F to Sleep Book Quotes Still Hit Different for Every Exhausted Parent

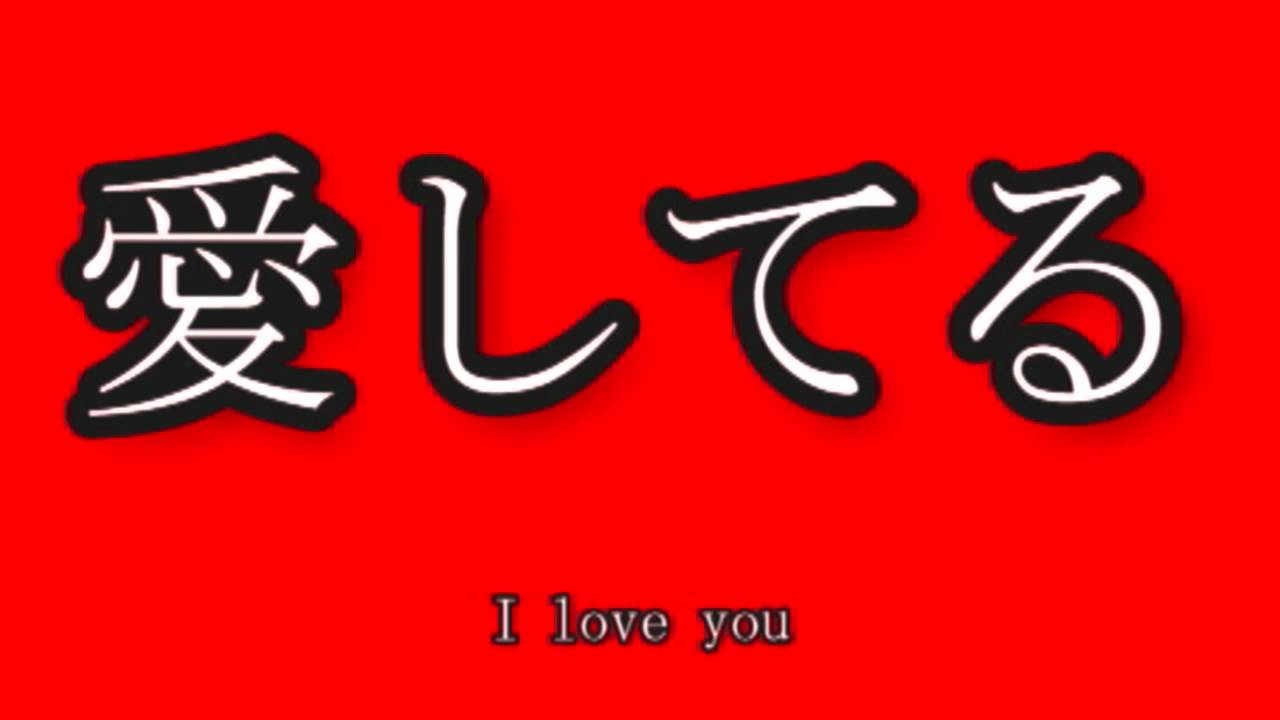

The Problem With Ai Shiteru

If you’ve spent any time on Google Translate, you probably saw Ai shiteru (愛してる). It’s the literal translation. It’s grammatically perfect. It’s also something many Japanese people go their entire lives without saying even once.

Think of Ai shiteru as the "big guns." It’s poetic. It’s cinematic. It’s the kind of thing you say on a deathbed or in a high-stakes marriage proposal. Use it on a third date and you’re basically telling the other person you’re ready to buy a house and name your future grandchildren together. It’s heavy.

Dr. Satoshi Kinsui, a linguist known for his work on "role language," has often touched upon how certain Japanese expressions exist more in fiction than in reality. Ai shiteru is the king of those expressions. It’s a "role" word. It sounds like something a hero says, not something a guy says over ramen.

How People Actually Say I Love You in Japanese

Most of the time, love isn't "love." It's "like."

The word you're looking for is Suki (好き).

It sounds casual, right? Like saying "I like this beer." And yeah, it is used for beer. But in a romantic context, Suki is the standard way to confess. When you add the intensifier Dai to make it Daisuki (大好き), you’re effectively saying "I love you" in a way that feels natural, warm, and real.

The Art of the Kokuhaku

In Japan, there's this specific cultural event called Kokuhaku. It’s the formal confession of feelings. You don’t just "hang out" until you’re dating; you usually have a clear moment where one person says, "Suki desu. Tsukiatte kudasai" (I like you. Please go out with me).

Without this step, you’re often stuck in a weird limbo.

But even within the Kokuhaku, people rarely jump to the "A-word." They stick to Suki. Why? Because Japanese culture prizes Enryo (restraint) and Ishin-denshin (telepathic communication). You’re supposed to feel the love through actions, not just hear it through a loud declaration.

Why Men and Women Say It Differently

Gendered language in Japan is shifting, especially with Gen Z in places like Shibuya or Osaka, but the echoes of traditional speech are still there.

A guy might use Ore (a masculine "I") when confessing, while a woman might use Watashi. But more importantly, the softness of the ending changes.

- Suki da yo: This feels a bit more masculine or assertive. The "da yo" adds a certain "I'm telling you this" vibe.

- Suki nan desu: This is more formal and slightly vulnerable. It’s common during that first big confession.

- Suki yo: Traditionally feminine, though you'll hear this less often in modern, casual Tokyo slang.

Language is a moving target. What your textbook printed in 2012 is probably already out of date.

Suki vs. Ai: The Technical Breakdown

If we’re being nerds about it, Suki is an adjective (na-adjective), not a verb. When you say you love someone, you're literally saying they are "likable" to you. Ai shiteru, however, is a verb. It’s an action. It’s something you do.

Japanese novelist Natsume Soseki famously (and perhaps apocryphally) told his students that the English phrase "I love you" should be translated as Tsuki ga kirei desu ne (The moon is beautiful, isn't it?).

He argued that a Japanese person wouldn't be so blunt. They would comment on the shared beauty of the moment. If you're sitting on a bench at night and your partner says the moon looks nice, they might not be talking about astronomy. They might be saying "I love you" without the risk of being too direct.

The Role of Silence and Actions

There’s a concept called Kuuki wo yomu, which means "reading the air."

In Western relationships, we get anxious if we don't hear "I love you" regularly. In Japan, constant verbal reassurance can sometimes be seen as suspicious or annoying. If you have to say it all the time, does it even mean anything?

Instead, love is shown through:

- Bento boxes: Making someone food is a massive "I love you."

- Safety: Walking someone to the train station.

- Time: Spending a "Day Off" together, which is a big deal in a work-obsessed culture.

If someone is doing these things, they’re shouting their love from the rooftops. They just aren't using their vocal cords to do it.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make

Don't go overboard. Seriously.

I’ve seen people try to use Kimi wo aishiteru because they saw it in a song. Using "Kimi" (a way to say "you") can actually sound a bit condescending or overly poetic depending on the context. Most of the time, you drop the word "you" entirely.

In Japanese, the subject and object are often omitted. If I look at you and say "Suki," it’s obvious who I like. Adding "I" and "You" makes it sound like a translated textbook sentence. It loses the intimacy.

Regional Flavors: Beyond Tokyo

If you’re in Osaka, things get fun. The Kansai dialect (Kansai-ben) is famous for being warmer and more boisterous.

Instead of Suki da yo, someone in Osaka might say Suki yanen.

It’s iconic. It’s so famous there’s even a popular brand of instant noodles with that name. It carries a sense of "I love ya!" rather than a stiff "I love you." It breaks the ice. It’s less scary.

The Evolution of Love in 2026

Modern dating apps like Pairs or Omiai have changed the landscape in Japan. People are becoming more direct because digital communication requires it. You can't really "read the air" through a smartphone screen as easily as you can in person.

However, even on these apps, the transition from Suki to Ai remains the ultimate milestone.

It’s worth noting that many younger Japanese couples are adopting more Westernized expressions of affection. Holding hands in public (te wo tsunagu) used to be rare; now it’s everywhere in Harajuku. But the language? The language is stubborn. The word Ai remains a sacred, rare thing.

Practical Steps for Expressing Your Feelings

If you’re actually in a situation where you need to use these phrases, don't overthink it. Language is about connection, not perfection.

- For a first confession: Stick to Suki desu. Tsukiatte kudasai. (I like you. Can we date?)

- For a long-term partner: Use Daisuki or Aishiteru if the moment is truly special—like an anniversary or a major life event.

- To be subtle: Use Soseki’s moon line if you’re feeling bold and a bit nerdy. Just make sure they know the literary reference, or they'll just think you're interested in the weather.

- To be casual: Throw a Suki da yo at the end of a phone call.

Japanese isn't just a set of labels for things. It’s a way of navigating social distance. Choosing the right version of "I love you" is basically you choosing how close you want to stand to someone.

Start with Suki. It’s safe, it’s sweet, and it’s what people actually use. Let the relationship build the weight behind the word. When the time comes for Ai shiteru, you’ll know. And more importantly, they’ll know, because you won't have used it a thousand times before it actually mattered.

To truly master this, your next move should be observing the non-verbal cues your partner gives. Pay attention to how they use Aisatsu (greetings) and small gestures of service. In Japan, love is a verb that is rarely spoken but constantly performed.

Watch a few modern Japanese dramas—not just anime—to hear the cadence of Suki in different emotional states. Shows like "First Love" on Netflix provide a much more realistic look at how these words land in modern conversation than any Shonen battle series ever will.