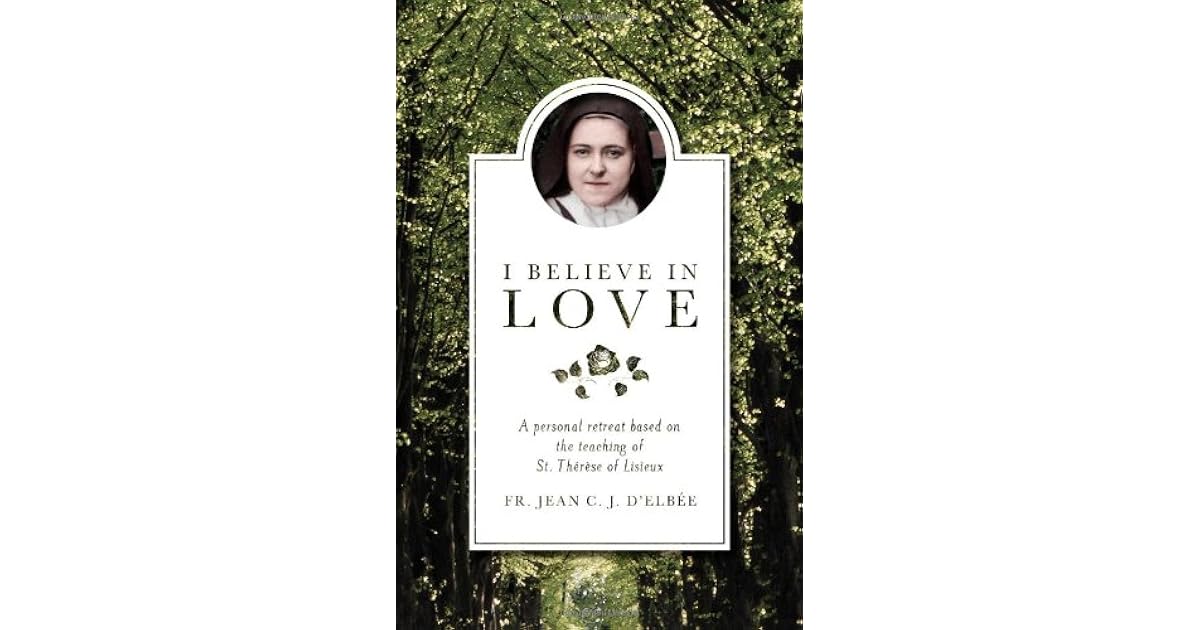

If you’ve spent any time in a Catholic bookstore or scrolling through spiritual reading lists, you’ve seen it. That simple, unassuming cover. It doesn’t scream for attention. But I Believe in Love by Father Jean C.J. d’Elbée has quietly become one of the most influential retreat books of the last half-century. It’s a bit of a phenomenon, honestly. It’s not a textbook. It’s not a dense theological manual that requires a PhD to decode.

It’s a conversation.

Specifically, it’s a series of retreat conferences based on the "Little Way" of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. But here is the thing: people often mistake Thérèse’s "little way" for something sentimental or fluffy. They see the roses and the "Little Flower" nickname and think it’s spiritual candy. D’Elbée kicks that door down. He shows that believing in love—real, divine love—is actually the most radical, difficult, and transformative thing a human being can do.

Why I Believe in Love Isn't Your Average Self-Help Book

Most spiritual books tell you to do more. Pray more. Fast more. Be better. D’Elbée takes a different tack. He focuses almost entirely on confidence. Not self-confidence—that’s useless here—but confidence in God’s mercy.

The book was originally titled Croire à l'Amour. When it was translated into English, it retained that core urgency. D’Elbée was a priest of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, and you can feel that specific lineage in his writing. He’s obsessed with the heart. He’s obsessed with the idea that we are loved not because we are good, but because God is good.

It sounds simple. It’s actually terrifying.

If you accept the premise of the I Believe in Love book, you have to stop relying on your own ego. You have to accept your "nothingness." That’s a word he uses a lot. It’s not meant to be degrading. It’s meant to be liberating. If you are nothing, then God can be everything.

The French Connection and the 1960s Context

Context matters. D’Elbée wrote these conferences in the mid-20th century. France was recovering from the trauma of World War II. The Church was on the cusp of Vatican II. In a world that felt fractured and increasingly cynical, d’Elbée doubled down on the simplicity of the Gospel.

He wasn't interested in the politics of the era. He was interested in the interior life. He saw that people were exhausted. They were trying to earn their way into heaven, and they were failing miserably.

"To believe in love is to believe that God loves us just as we are," he basically says throughout the chapters. He doesn't wait for you to be "fixed" before he tells you that you're loved. This is a massive shift from the Jansenist tendencies that had plagued French spirituality for centuries—that cold, rigid, "God is a harsh judge" vibe. D'Elbée burned that bridge.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

The Three Pillars of d'Elbée's "Little Way"

If you're looking for a roadmap in this book, it's not laid out in a 10-step plan. It’s more organic. However, three themes dominate every page.

1. The Power of Abandonment

This isn't abandonment in the sense of being left alone. It's the French abandon, which means surrendering or letting go.

D’Elbée argues that our biggest problem is that we try to drive the car. We worry about the future. We obsess over our past sins. We fret about our reputations. He suggests—quite forcefully—that we should just stop. He writes about "blind confidence." It’s the idea of a child falling asleep in their father’s arms while a storm rages outside. The child doesn't need to know how the roof is built or how the storm works. The child just needs to know they are held.

2. Mercy Over Merit

This is where the I Believe in Love book gets uncomfortable for the perfectionists.

We love our checklists. We love feeling like we "earned" a good day because we did all our chores and said all our prayers. D'Elbée says your merits are like "dirty rags" compared to the ocean of God's love. He points out that St. Thérèse wanted to go to God "empty-handed."

Why? Because if your hands are full of your own "good works," there’s no room for God to fill them with His gifts. It’s a paradox. To be spiritually rich, you have to stay spiritually poor.

3. The "Spirit of Childhood"

This isn't about being childish. It’s about being childlike.

There’s a nuance here that most people miss. A child is dependent. A child expects to be taken care of. D’Elbée pushes the reader to reclaim that sense of wonder and total reliance. He uses the image of the elevator. St. Thérèse famously said she was too small to climb the steep stairs of perfection, so she sought an "elevator" to carry her up. That elevator is Jesus’s arms.

The Reality of Suffering in D'Elbée's Writing

Don't think for a second this is a "prosperity gospel" book. It’s not.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

D'Elbée is very clear: you will suffer. You will fail. You will fall into the same stupid sins over and over again. Honestly, that’s one of the most refreshing parts of the book. He doesn't expect you to stop being human.

He talks about "the apostolate of the smile." It’s the idea of choosing joy even when things are going wrong. Not a fake, plastered-on smile, but an interior peace that comes from knowing that even your suffering is handled by Love.

He spends a significant amount of time discussing the "Dark Night." He acknowledges that sometimes God feels absent. In those moments, "believing in love" isn't a feeling. It's a choice. It's an act of the will.

How to Actually Read This Book (Because It's Easy to Do It Wrong)

If you try to speed-read I Believe in Love, you’ll miss the point. It’s meant to be chewed on.

Don't Treat It Like a Narrative

There is no plot. It’s a series of reflections. You can open to almost any page and find something that hits you in the gut.

Watch Out for the "Old-School" Language

Some modern readers struggle with d’Elbée’s style. It can feel a bit formal or "churchy" at times. You have to look past the 1940s-era piety to see the psychological depth underneath. He was actually quite ahead of his time in understanding how shame and anxiety cripple the human spirit.

The "Peace" Test

D’Elbée has a very simple metric for whether you are on the right track: Peace.

If your "spirituality" makes you anxious, restless, or judgmental of others, he’d say it’s not from God. God is the God of peace. Even when we are corrected, there is a sense of calm. If you feel a frantic need to be perfect, you've stopped believing in love and started believing in yourself again.

Common Misconceptions About the "Little Way"

Since the I Believe in Love book is the gold standard for understanding Thérèse of Lisieux, it’s worth clearing up what the "Little Way" is not.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

- It’s not an excuse for laziness. Surrender is an active choice. It takes more work to trust God in a crisis than it does to panic.

- It’s not just for "holy" people. D'Elbée specifically wrote for the "little souls"—the people who feel like they are failing at life and faith.

- It’s not about ignoring sin. It’s about bringing sin to the light immediately so it can be dissolved by mercy, rather than brooding over it.

The Legacy of Jean d'Elbée

Father d'Elbée wasn't a celebrity priest. He didn't have a massive platform. He simply gave these talks to a group of sisters. But the sisters realized the power of what he was saying. They transcribed the talks. They shared them.

Decades later, the book is a staple for retreats. It has been translated into dozens of languages. It remains in print because the human condition hasn't changed. We are still anxious. We are still perfectionists. We are still afraid we aren't "enough."

D’Elbée’s message is the ultimate "enough."

Putting the "Belief in Love" Into Practice

So, what do you actually do with this? If you’ve finished the book, or if you’re just starting, the application is surprisingly practical.

Accept your weaknesses. Stop being surprised when you fail. D'Elbée suggests that we should almost be "glad" of our weaknesses, because they are the very things that draw God's mercy to us. When you mess up, don't argue with yourself for three days. Just say, "Lord, see? This is what I'm capable of when I'm on my own. I need you."

Practice the "Present Moment." Fear lives in the future. Guilt lives in the past. Love lives right now. D'Elbée emphasizes that God gives us grace for the next five minutes, not the next five years.

Give what you have. If you only have five minutes of patience, give that. If you only have a "widow's mite" of energy, give that. The quantity doesn't matter; the love behind it does.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Reader

- Read one chapter at a time. Seriously. Let it sit for a week.

- Identify your "perfectionist" triggers. Where are you trying to earn love rather than receive it?

- Use the "Jesus, I trust in You" aspiration. It’s the shorthand version of d’Elbée’s entire philosophy.

- Audit your peace. If you lose your interior peace, stop and ask: "Am I trying to carry a burden that isn't mine?"

The I Believe in Love book isn't just a book to be read; it's a lens to be worn. It changes how you see your failures, your neighbors, and the character of the Divine. It's about moving from a contract-based relationship with the world—I do this, I get that—to a covenant-based relationship—I am loved, therefore I can be.